My awareness of CHS’s interest in the future of scholarly publishing was one of the reasons why I was eager to come to Washington this semester. As manager of a research center and a part-time librarian (i.e., someone who lies awake at night worrying about budgets), this is an issue that has also been on my mind for some time. And not simply the matter of increasing costs: The culture of the library has also had a significant impact on my views about the accessibility of scholarship. Its influence has led me, for example, to post the full text of all of my research on our departmental website. (If you’ve not thought much about how you present your research and manage your intellectual property, I encourage you to take a look here, though doubtless your own institutions have comparable initiatives.)

Another of the hats that I wear is that of series editor: I am responsible for the Tebtunis Papyri. The next few volumes of P.Tebt. will appear in major university presses. For my own volume in the series (no. IX), I wanted, however, to move away from traditional print venues and do something web based (without excluding a print-on-demand option for those who desire paper). The web has advantages beyond cost and accessibility: I believe, in fact, that it is much better suited for editions of papyri than paper is. In the first place, papyrological editions are volatile: In my sub(sub!)specialty, documentary papyrology, there are twelve (and counting) volumes of corrections to published papyri. The web makes correction easier and quicker (on average it takes three years to produce a volume of the Berichtigungsliste der griechischen Papyrusurkunden aus Ägypten). Time is an issue, of course, for the production of text editions themselves: A volume of, say, seventy papyri takes a good while to complete even if one devotes her/his energy to it exclusively, to say nothing of the period that the publisher requires to produce the book. Web publication is not only faster, it can be incremental—I am thinking not only of the possibility of posting a few texts at a time, but also drafts—and from the very beginning of the process, the papyrologist can benefit from the input of a much broader community (editing papyri is inherently collaborative). Finally, the web enables a papyrus’ material context (when known) to be illuminated more easily and affordably, and it allows for a “layered” presentation, i.e., one capable of addressing multiple audiences (e.g., specialists, students, the general public).

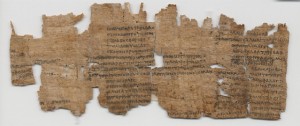

P.Tebt. IX will be an edition of the “archive” of the priests of the crocodile god Soknebtunis. This assemblage of papyri runs from the last quarter of the first century CE into the third and is comprised of texts (both documentary and literary) in Greek and various forms of Egyptian. In future posts I will write more about the archive’s contents and, especially, the questions that it poses, but for today, I would like to do some thinking out loud about the online edition itself (and to encourage you to provide feedback). Here is what I am envisioning at the moment (ht to my TBL colleague Francesco Spagnolo & Memory Miner):

- The table of contents for the edition will consist of thumbnail images of all of the papyri in the archive. Though the siglum and publication number of each piece will be indicated when the cursor runs over it (and there will, of course, be a search box and/or menu), I want to encourage the sort of browsing that one does when one opens a box of unstudied papyri.

- Double-clicking on a papyrus’ thumbnail will bring up its full-size image. The surface of this full-size image will be tagged: certainly its geographical and personal names—more on these in a moment—but ideally every word of text. This would be a fantastic teaching tool: Click on a bit of ink, and the writing of the whole word is highlighted; click on the highlighted word, get its transcription in Unicode Greek (or Egyptian transliteration) and its possible definitions. (The Mellon-funded Integrating Digital Papyrology project, which is directed by former CHS fellow Josh Sosin, has a dedicated papyrological lexicon in the works.) Users should also be able to place their own tags; these might be private (study notes, e.g.) or public (e.g., “I think that the reading here is wrong.”)

- Clicking on a geographical name tag will highlight the writing of the name and give it to you in transcription; double-clicking will open a new window and take you to its location in Google Earth. (At the moment I do not know enough about the Pleiades Project to consider integration with it.) Users will be able to navigate in this “geo window,” so if one wants to see all of the papyri (and, ideally, other archaeological material) from a site (or even a structure), one need simply click on the entity in question.

- Clicking once on a personal name tag will highlight its writing and give it to you in transcription. Double-clicking will open a new window with thumbnails of all of the texts (in chronological order) in which this person appears.

- Adjacent to the full-size image will be buttons to pull up the complete text of the papyrus and a line-by-line commentary. Greek texts (and possibly their commentaries, depending on how quickly the Integrating Digital Papyrology team is able to make this feature available) will be entered directly into the Duke Databank using the SoSOL editor and paged from Duke to ensure appearance of the latest version of the text (since SoSOL also accepts corrections from its users). Using SoSOL also solves the peer review “bugbear,” since all Duke texts are vetted by an editorial board. A comparable solution remains to be found for the Egyptian texts.