Tsivikis, Nikos. "An Early End to Antiquity in Roman Provincial Greece: Pagans and Christians in the Wake of the 365 CE Earthquake in Messene." CHS Research Bulletin 9 (2021). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:TsivikisN.An_Early_End_to_Antiquity_in_Roman_Provincial_Greece.2021.

Introduction

Messene in the southwestern Peloponnese was one of the most important cities of the region during the Hellenistic and Roman period. Its description by Pausanias in the second century captured the image of an ancient religious center with a multitude of monuments. The fourth century would mark for the city and its inhabitants a series of radical changes and innovations that transformed the city center in the context of new and renewed uses. The archaeological investigation of domestic and public buildings across the city that change in order to meet the needs of a shifting society along with rich new excavation material has offered research a much better understanding of wider transformations occurring across the empire. Prominent among these new buildings is the remodeling or construction anew of urban residences for the elite of the town that occupy space in the civic center of Messene, traditionally reserved only for public buildings and city shrines. Among the newly constructed buildings are luxurious urban mansions, semi-public audience halls and a Christian assembly hall, perhaps in use as early as the third century. At the same time, the creation of new statues, both imperial and cultic, continued, that now found a setting inside these luxurious residences and the domestic space.

The question

My research at CHS started on one hand with a magnitude of newly documented fourth century material from the systematic excavation of Messene in the SW Peloponnese and on the other with a set of questions regarding Late Roman Messenian society that intended to make better sense of the existing material. As detailed elsewhere these questions varied from: What did it mean to live in a Roman provincial city of the Peloponnese in the middle of the 4th century? How did the Constantinian ‘revolution’ affect the lives and ideas of people who resided equally far away from the old capital of Rome and the new capital of Constantinople? And how would these people interpret the sweeping changes of mindsets and everyday practices that Christianity was bringing along, as it became initially legitimized and later institutionalized?

These are usually questions that cross the minds of historians and archaeologists working on fourth century Peloponnese, and usually we have been resorting to the scarce textual sources or few datable visual culture monuments in order to answer them, even in sites with long standing excavations like Corinth (Brown 2017). In the excavation of Messene in the SW Peloponnese, we have lately a unique opportunity to revisit such questions based on archaeological material discovered in a distinct destruction layer covering a large area of the site that can be associated with the earthquake of 365 CE.

The Earthquake

It was in the last days of July of 365 CE that one of the greatest seismic phenomena in antiquity struck the eastern Mediterranean hard, with an epicenter near the coast of western Crete that also caused a catastrophic tsunami. This earthquake had disastrous effects across a large part of Roman Eastern Mediterranean, from Alexandria to Crete and from Cyprus to South Peloponnese (Stiros 2001, 2020). Although most of the research has focused on Crete, new evidence has been showing that the region of the SW Peloponnese must have been severely affected. The consequences of the earthquake in Messenia were described vividly a few years later in the works of Ammianus Marcellinus (Hist. 26.10.15-19) when referring to Methone, a coastal town a few miles to the west of Messene, he saw a heavy ship that had been washed ashore two miles inland by the tsunami (Kelly 2004). Up until today, only a few archaeological sites in the region have explored the possibility of identifying the results of the earthquake, and Messene thus presents a unique and original picture, supported both by excavation finds and by archaeoseismological data.

The physical remains

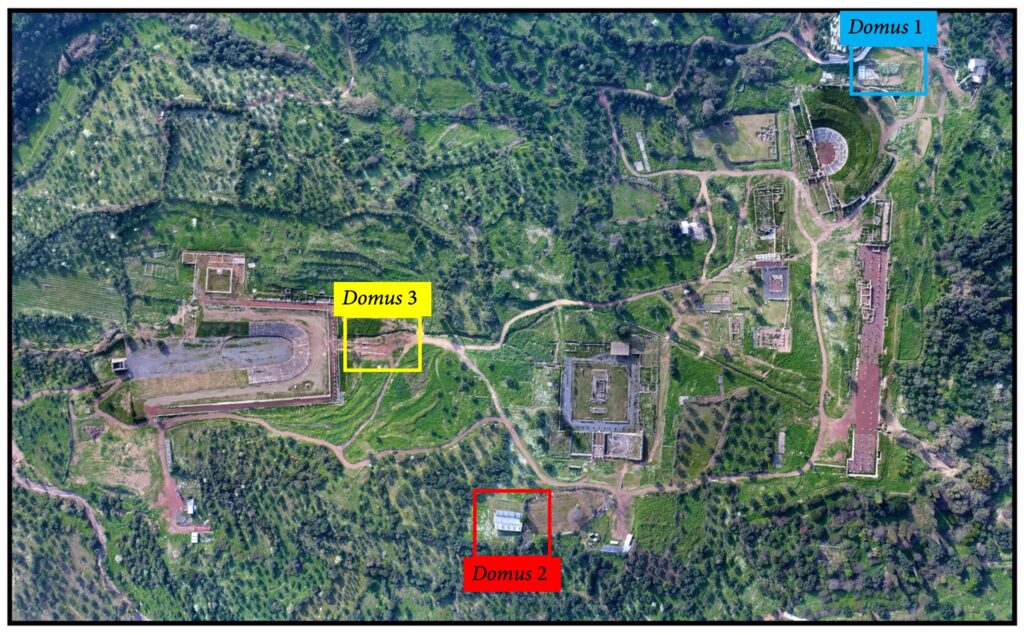

In the center of my research as an Early Career Fellow at the Center for Hellenic Studies stood three traditional Roman urban mansions (domi) that had been or are currently under excavation as part of the project of Messene (fig. 1). All three of them, situated in the city center of Messene, were constructed at some earlier point in Roman imperial times, while their later phases can be dated in the third and fourth centuries. Finally in all three of these we can prove that their use terminated in the second half of the fourth century as a result of a violent event, most probably the destruction by the 365 earthquake.

These domi were more than just housing units of the Late Roman Messenian elite, they express Late Roman attitudes on built space, religious practice and interaction with the urban fabric. Domus 2, next to the temenos of Asclepius, served possibly as the seat of a local archon or person of great authority who granted audiences to the clientele in a marble-clad main hall surrounded with images of the emperor and the old gods. Domus 3, close to the stadium and gymnasium complex of the city, had official rooms with mosaics depicting enigmatic scenes of a divine couple with no clear attribute identifying them. Several possibilities can be proposed: Dionysus and Ariadne, Hylas and Nymphs, Adonis, etc, all of which share the character of Late Roman mystery cults. Then domus 1, near the theater of Messene, exhibits clear evidence that it was converted in the course of the third century into a Christian assembly hall, that was then further modified and remained in use during the fourth century until its final destruction by the earthquake (Tsivikis 2018). Such finds offer an archaeological outline of the Late Roman provincial society of Messene in the wake of Christianity, in ways of understanding and at a depth that no historical account could offer for a medium-sized provincial town in the Peloponnese.

Out of this multitude of material during my research as an Early Career Fellow I focused on different aspects of the fourth century in Messene, and some of the relevant iconic finds. The religious situation at the time, either as peaceful and complimentary coexistence or as growing and evolving antagonism stands in the epicenter of my approach. Systematic excavation and research opened new insights to some of these elements, as can be seen in some characteristic examples.

Firstly, I was able to assess the material of the excavation from the domus 1near the theater, and thus reconstruct the sequence of its building phases (fig. 2). It was made clear based on detailed study of the stratigraphical data, most importantly coins, that the main room of a pre-existing early imperial Roman domus was remodeled shortly after 260 CE with the laying of finely made mosaic floors into a new assembly hall by an anagnostes Paramonos, probably for the use of the nascent Christian community. A couple of generations later, in the fourth century and between 310s and 360s the assembly hall was expanded and further remodeled, this time by the leader of the Christian community an episkopos Theodoulos. The two individuals put their names in donor inscriptions set in the mosaic floors they were responsible for. This Christian assembly hall, a domus ecclesiae, is one of the earliest known in the Greek peninsula and elucidates the presence of early Christian communities in Late Roman cities and especially Messene.

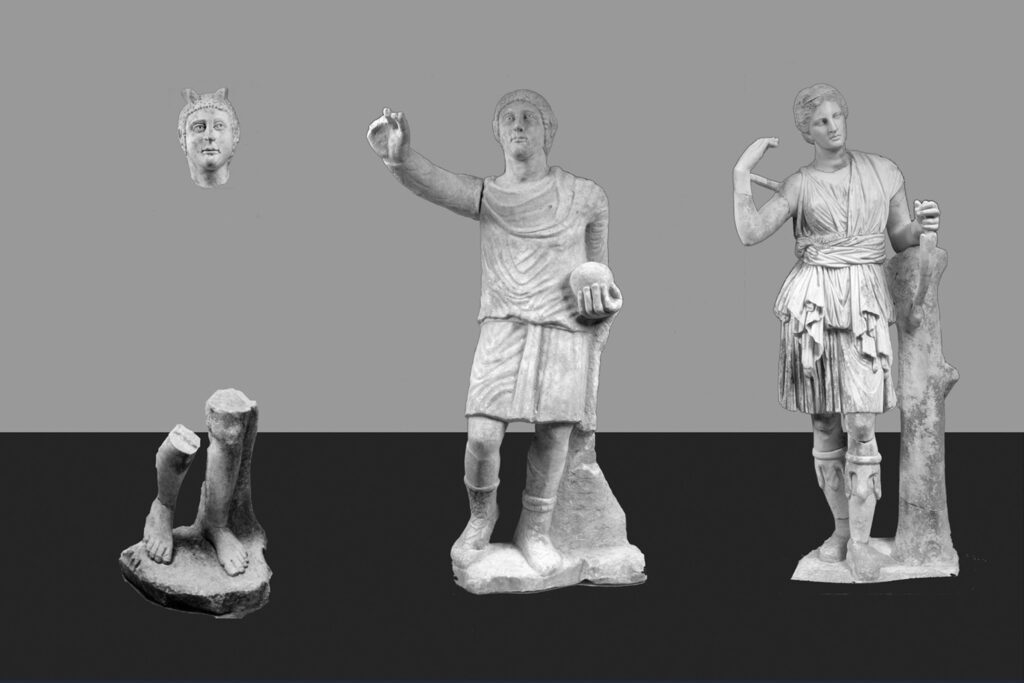

At the same approximately time and in another part of the city a different process was documented. In Late Roman domus 2 east of the temenos of Asklepios, a group of statues had been found adorning niches at the far wall of the main hall of the domus (fig. 3).These included two original fourth century creations: an imperial portrait of a Constantinian emperor and an image of Hermes (Deligiannakis 2005; Tsivikis 2017). For years these sculptures were regarded as part of the original decoration of the Late Roman urban mansion. New research though made possible to link the imperial statue with an inscribed base for emperor Constantine I found elsewhere in the city and originally dedicated in a public setting (fig. 4). Thus, the statues of emperor and Hermes should be understood quite differently, as they would have been initially set during the early reign of Constantine I to be exhibited near some type of shrine, and then probably during the reign of Valentinian I and before 365 they were removed from public sphere and set anew inside a private space in a different context and probably for a different use.

This reversed process of private to public for the Christian building and from public to private for the Pagan statuary in fourth century Messene are telling of the developments taking place in a transforming society, and they provide a commentary on religious aptitudes inside the built space environment, underlining notions like monumentalization and domestication of religious practice.

During my CHS research I published a paper on the “Christian Inscriptions from a Third and Fourth-Century House Church at Messene (Peloponnese)” that will appear in 2022 in the peer-reviewed Journal of Epigraphical Studies (vol. 5). Also, I’ve concluded the relevant chapters on the fourth century Messene for my monograph: Urban Transformation, Christianization and Ruralization in Late Antique Peloponnese: Byzantine Messene from Antiquity to the Middle Ages (300-1000 AD), that will appear in 2022 in the series Byzanz zwischen Orient und Okzident at Mainz, Germany. While certain aspects of this project were or will be presented in invited seminars and talks at University of Kiel (August 2021) and at the Leibniz Research Institute for Archaeology, RGZM-Mainz (November 2021); a concise overview of my research at the CHS will be presented in the international conference “Twilight of the Gods: Greek Cult Places and the Transition to Late Antiquity” (Athens, October 2021).

Selected Bibliography

Brown, A. 2017. Corinth in Late Antiquity: A Greek, Roman and Christian City, London ; New York.

Deligiannakis, G. 2005. “Two Late-Antique Statues from Ancient Messene.” Annual of the British School at Athens 100: 387-406.

Kelly, G. 2004. “Ammianus and the Great Tsunami.” Journal of Roman Studies 94: 141-167.

Stiros, S. 2001. “The AD 365 Crete earthquake and possible seismic clustering during the 4-6th centuries AD in the Eastern Mediterranean: A review of historical and archaeological data.” Journal of Structural Geology 23: 545-562.

Stiros, S. 2020. “Wass Alexandria (Egypt) Destroyed in AD 365? A Famous Historical Tsunami Revisited.” Seismological Research Letters 20: 1-12.

Themelis, P. 2002. “Υστερορωμαϊκή και Πρωτοβυζαντινή Μεσσήνη.” In Πρωτοβυζαντινή Μεσσήνη και Ολυμπία: Αστικός και αγροτικός χώρος στη Δυτική Πελοπόννησο, ed. P. Themelis and V. Konti, 20-58, Athens.

Themelis, P. 2018. “Η Μεσσήνη της ρωμαιοκρατίας και η ανακύκλωση του παρελθόντος.” In What’s New in Roman Greece? Recent Work on the Greek Mainland and the Islands in the Roman Period, ed. V. Di Napoli, F. Camia, V. Evangelidis, D. Grigoropoulos, D. Rogers, and S. Vlizos, 419-436, Athens.

Tsivikis, N. 2017. “Οι τελευταίοι Εθνικοί στη Μεσσήνη του 4ου αι. μ.Χ.” In Ιερά και Λατρείες της Μεσσήνης από τα αρχαία στα βυζαντινά χρόνια, ed. P. Themelis, M. Spathi and K. Psaroudakis, 269-289, Athens.

Tsivikis, N. 2018. “Πρώτες παρατηρήσεις σε κτήριο με χριστιανική χρήση στη Μεσσήνη του 4ου αι. μ.Χ.” In 38ο Συμπόσιο Βυζαντινής και Μεταβυζαντινής Αρχαιολογίας και Τέχνης, ΧΑΕ-Περιλήψεις, 112-113, Athens.