Scalora, Francesco. “The Diary of Cesare Vitali.” CHS Research Bulletin 10 (2022). http://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:102284670.

Early Career Fellow in Philhellenism 2021-22

Abstract

Among the numerous testimonies concerning the 1821 Greek Revolution, Cesare Vitali’s account has not yet been investigated and his figure is still relatively unknown. Doctor and vice-consul of the Kingdom of the two Sicilies in Athens during the crucial years of the Greek Independence Wars, Cesare Vitali witnessed all of the political turmoil associated with the city: from the first attempt of liberation from the Ottoman conquerors (April 1821) to the dramatic events that led to the siege of Athens and the surrender of the Acropolis in May 1827. The CHS fellowship in Philhellenism, offered on the occasion of the celebration of the 200 years (1821-2021) since the outbreak of the Greek Revolution, gave me the opportunity to fully address the case of Cesare Vitali and to study his diary in detail, which has now been published for the first time in the prestigious series “Quaderni” of the Istituto Siciliano di Studi Bizantini e Neoellenici “B. Lavagnini”.

Italian Philhellenism

Within the pan-European phenomenon known as Philhellenism, which resonated explosively throughout the nineteenth century, Italy, due to its history, geographical location and political status, was prominent in a different way.

Italy offers a particularly important vantage point for understanding the importance of Philhellenism in 19th century Europe. The Italian Philhellenic phenomenon is distinguished by its intensity, impact and political repercussions on the process of formation of the Italian State and its idea of the nationhood, even in a society that is still politically divided and not united, but ideologically united by the convergence of liberal ideas and national redemption. Greece appears as a space in which to experiment, after the first Piedmontese and Neapolitan failures, with a common struggle (Noto 2016 and Scalora 2018, 27-122).

The peculiarity of the Italian philhellenic movement is mainly distinguished by two phenomena: the philhellenic inspired literary production published throughout Italy in the aftermath of the Greek Revolution (Scalora 2018), and the active participation of Italian volunteers working for Greek Independence. To date, scholars have paid particular attention to the first phenomenon, neglecting to investigate the significant contribution of a considerable number of exiles and patriots who went to Greece, fighting alongside the Greek insurgents (Isabella 2011, 87-122). There is little statistical data available on the number of Italians who went to Greece. Moreover, little or nothing is also known about their activity on Greek territory (Lukatos 1996). First came the memories of great deeds. Like the other Europeans and the Americans who came to the aid of the Greeks, the Italians also had their legendary philhellenes: Pietro Gamba, Giuseppe Pecchio, Santorre di Santarosa are the best known names. In the shadow of the most famous ones, however, the activity of individual personalities is hidden, whose contribution also deserves attention. Their political and cultural activity and the ideological dimension in which they acted restores to us the image of a complex phenomenon, matured in the shadow of great names and enterprises.

Reconstructing the story of these characters is not an easy task. While in some cases the Italian Archives give us an incomplete picture of their public life in Italy, almost nothing is given to us about their intense activity in Greece. The case of Cesare Vitali is an exception.

Cesare Vitali: Doctor and vice-consul of the kingdom of the two Sicilies in Athens

Τὴν 2 τοῦ παρελθόντος Δεκεμβρίου ἐτελεύτησεν ἐνταῦθα ὁ φιλέλλην ἰατρὸς Καῖσαρ Βιτάλης. Ἰταλὸς τὸ γένος, ἦλθε πρὸ εἴκοσι ἐτῶν εἰς τὴν Ἑλλάδα, καὶ πολιτογραφηθεὶς καὶ νυμφευθεὶς εἰς Ἀθήνας, ὠφέλησεν ὄχι ὀλίγον μετερχόμενος τὸ φιλάνθρωπον ἐπάγγελμά του. Εἰς τὰς ἀρχὰς τῆς ἐπαναστάσεώς μας, μολονότι ὑποκείμενος εἰς χρέη ἐξωτερικοῦ ὑπουργήματος, πρόξενος ὢν Νεαπόλεως, δὲν ἔλειψε, καθόσον τὰ φιλελεύθερα αἰσθήματά του ἐσυμβιβάζοντο μὲ τὰ χρέη του, νὰ ὠφελήσῃ τοὺς Ἕλληνες καὶ μὲ λόγον καὶ μὲ ἔργον, στερηθεὶς καὶ αὐτὸς ὅλης τῆς καταστάσεώς του μετὰ τῶν λοιπῶν Ἀθηναίων. Αἰωνία του ἡ μνήμη!

On January the 7th, 1828, the editors of the Γενικὴ Ἐφημερὶς τῆς Ἑλλάδος (No. 2, p. 8) announced the death of physician Cesare Vitali, which had probably occurred in Aegina about a month earlier, on December the 2nd, 1827. They remembered and praised the sensitivity of a man who warmly supported the Greek insurgents in many ways. The «proto-surgeon doctor of Athens», who had spent the last sixteen years of his life in Athens, where he worked as a diplomat on behalf of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1825), was a firm believer in the Philhellenic cause, which was not always compatible with his diplomatic duties. However, he also went down in history for writing in Italian – on June the 17th, 1825 – a highly controversial medical report on the death of Odysseas Androutsos, one of the key protagonists of the 1821 Greek Revolution.

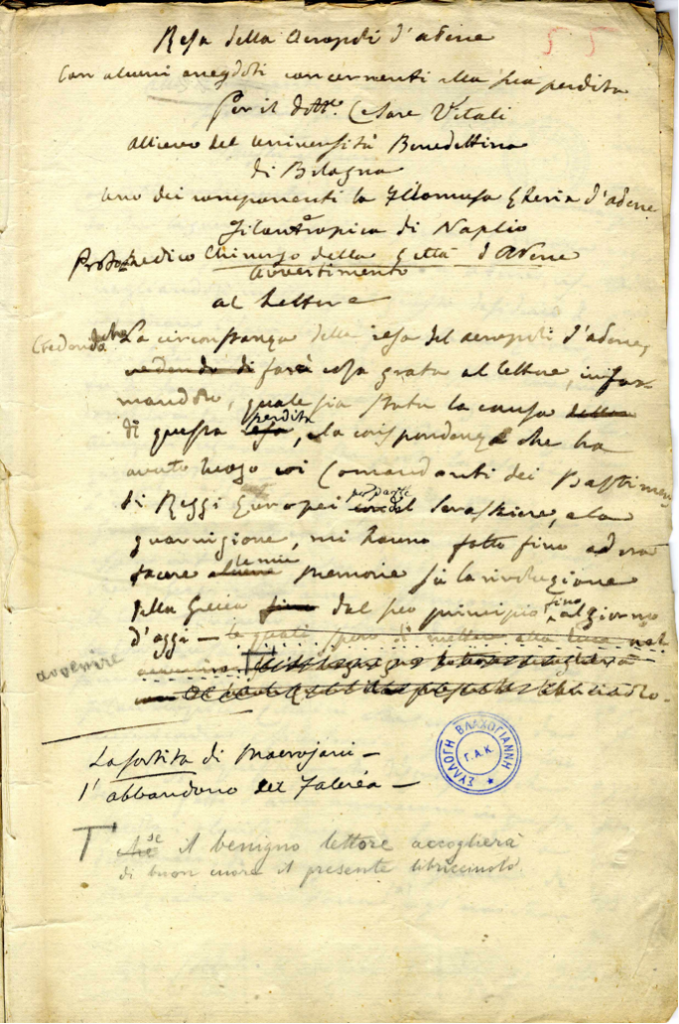

At first, it would seem that these few facts already give us already an insight into the important role played during the first Greek insurrections by Vitali, whose name joined those names of other Italian proscribed, exiled and patriotic Italians who, at the very beginning of the Revolution and after the failure of the Piedmontese and Neapolitan riots, left the Italian mainland for Greece, bringing with them their aspirations and hopes. But, in reality, Vitali, whose stay in Athens dates back to the first decade of the 19th century, was already an active member of the small Athenian society when his compatriots were running to Greece to offer military and medical assistance as well as help with the provision of supplies and administrative tasks. This is proved by the extensive documentation (Scalora 2021, 9-21) that allows us to reconstruct the phases of his stay in Athens, along with the profiles of his circle of friends in the city. According to this archive material, he was already an ephor of the Filomousos Etereia of the city and later a member of the Filanthropiki Etereia in Nafplio. These documents include writings by Cesare Vitali, providing evidence of the great interest of the Italian doctor for the events that led to the Greek Revolution and in which he played a vital role on several occasions. The papers are now part of the Vlachojannis Collection (Συλλογή Βλαχογιάννη, Β΄ Κατάλογος Χειρογράφων, Θ΄Ἡμερολόγια Ἐπαναστάσεως, mss. 53-55) and are held at the General National Archives (Γενικά Αρχεία του Κράτους) in Athens.

Cesare Vitali’s diary

The autographs by Vitali, as Nikos Karapidakis and Anna Kulikurdi (Karapidakis, Kulikurdi 2012, 50-51) inform us, were found by Jannis Vlachojannis «στο βιβλιοπωλείο του Γ. Παπαϊωάννου στο παλαιό Ταχυδρομείο στην οδό Λυκαβηττού», most likely together with the other papers that would be included in the first volume entitledἈθηναϊκὸν Ἀρχεῖον, as part of the series Ἀρχεῖα τῆς Νεωτέρας Ἑλληνικῆς Ἱστορίας, curated by Vlachojannis himself (Vlachojannis 1901). Certainly before 1895, the year in which he mentioned the existence of the autographs in a pamphlet about the death of Androutsos:

Εἶναι κοντὰ δυὸ χρόνια ἀπὸ τότε ποῦ κατὰ τύχη ἔπεσαν ᾽ς τὰ χέρια μου κάποια ἔγγραφα ἱστορικὰ ὄχι ὀλίγα καὶ πολὺσπουδαῖα, ὅσο ἠμπόρεσα νὰ ἐξετάσω καὶ νὰ κρίνω ἀπὸ τὴν μελέτην των ὡς τὰ σήμερα. Εἶναι τὰ περισσότεραἡμερολόγια, γραμμένα εἰς Ἰταλικὴν γλῶσσαν, μὲ τὸ ἴδιο καὶ μὲ τὸ πρῶτο χέρι ἀπὸ τὴν ἀρχὴ ὡς τὸ τέλος, καὶ κάνουνλόγο διὰ τὴν ἱστορίαν τῶν Ἀθηνῶν κατὰ τὸν καιρὸν τοῦ Ἱεροῦ Ἀγῶνος. Ἀρχίζουν ἀπὸ τὴν ἀρχή, ὅταν οἱ ἐπαναστάταιχωρικοὶ τῆς Ἀττικῆς ἐμβῆκαν ᾽ς τὰς Ἀθήνας καὶ ἀπέκλεισαν τοὺς ἐχθροὺς εἰς τὸ κάστρο, καὶ τελειώνουν εἰς τὰ 1827,ὅταν ἡ Ἀκρόπολις παρεδόθη πάλι ᾽ς τοὺς ἐχθρούς, καὶ ἠμπορεῖ νὰ εἰπῇ κανεὶς πῶς τελειώνει τότε καὶ ἡ ἱστορία τῶνἈθηνῶν κατ᾽ ἐκείνους τοὺς χρόνους.

(Vlachojannis 1895, 5)

Both Vlachojannis’ words and the explanations provided by Karapidakis e Kulikurdi would deserve a more careful investigation to better understand at least the events relating to Vitali’s writings from his death (1827) to their discovery. It must also be said that Vlachojannis, whose figure is strongly connected to the study of the Greek Revolution and the creation of the Greek State Archives, spent the last decades of the 19th century tirelessly searching for writings, collections and documents about the Revolution, which were disseminated all around Athens. Upon their discovery he archived them, thereby saving them from certain dispersion by filing them (Stafilas 1995).

And while Vitali’s writings were found – by a stroke of luck – in the damp and dusty basement of an old Athenian library, other documents were stored in very unusual locations. Just to provide some examples, Dimitrios Christidis’ archive was found in a grocer’s shop at No. 16 Kolokotroni street («ἐν τῷ παντοπωλείῳ Χ. Κανάκη, ὁδὸς Κολοκοτρώνηἀριθ. 16»); the Samiakon Archeion was found in a building yard at No. 100 of the very central Athinas street («ἔν τινιμάνδρᾳ οἰκοδομικῶν ὑλῶν ἐπὶ τῆς ὁδοῦ Ἀθηνᾶς ἀριθ. 100»); a collection of documents on the siege of Missolungi was discovered in a sheepfold in the lagoon city; other papers, relating to the Ottonian period, in a small butcher shop at the intersection between Solonos and Mavromichali streets («ἐν μικρῷ κρεοπωλείῳ ἐπὶ τῆς διασταυρώσεως τῶν ὁδῶνΣόλωνος καὶ Μαυρομιχάλη»); lastly, many other collections were purchased at public auctions (Vlachojannis 1901, ε´-στ´). This was a race against time led by Vlachojannis, difficult and dictated by personal interests, always inspired by the symbolic value of memory and future research on the history of the Greek Revolution.

Among Vitali’s the several autographs, the key manuscript is, without a doubt, ms. 54. It includes the papers from his Diary, now published for the first time in the prestigious series “Quaderni” of the Istituto Siciliano di Studi Bizantini e Neoellenici “B. Lavagnini” (Scalora 2021). The Diary focuses on the historical events that took place in Athens during the crucial years of the Revolution, from the first Greek attempt to liberate the city (April 1821) to the siege of the Acropolis in May 1827, the same year in which Vitali died.

Considering its chronological extension, the meticulousness of the data reported and the detailed description of the historical events analysed, Vitali’s Diary is a unique text among the vast and rich production in the Italian language, written during the years of the Greek Revolution. Vitali’s diary not only brings to light the activity of an Italian personality who acted in an Athenian environment during the crucial years of the Revolution, but also offers scholars a historical source of considerable importance. For this reason, it seemed to us that it could be published separately, although we are convinced that in the future a more comprehensive investigation, aiming to examine the intense activity of Vitali in Greece, cannot neglect the other his writings, especially those collected in ms. 53.

Selected Bibliography

Isabella 2011 = M. Isabella, Risorgimento in esilio. L’internazionale liberale e l’età delle rivoluzioni, Bari 2011 (original edition: Risorgimento in Exile. Italian Émigrés and the Liberal International in the Post-Napoleonic Era, Oxford – New York 2009).

Karapidakis, Kulikurdi 2012 = N. E. Karapidakis, A. Kulikurdi, Η στιγμή Βλαχογιάννη, in M. Ch. Vakalopulu, N. E. Kapapidakis (eds.), Αρχειονομία, η πρακτική των Γενικών Αρχείων του Kράτους, Athens 2012, pp. 39-55.

Lukatos 1996 = S. D. Lukatos, Ο Ιταλικός Φιλελληνισμός κατά τον Αγώνα της Ελληνικής Ανεξαρτησίας, 1821-1831, Atene 1996.

Noto 2016 = A. G. Noto, La ricezione del Risorgimento greco in Italia (1770-1844). Tra idealità filelleniche, stereotipi e Realpolitik, Roma 2016.

Scalora 2018 = F. Scalora, La presenza della Grecia moderna nella cultura siciliana del XIX secolo, Palermo 2018.

Scalora 2021 = F. Scalora, Atene 1821-1827 nel Diario di Cesare Vitali, Palermo 2021.

Stafilas 1995 = M. Stafilas, Ο αγώνας του Βλαχογιάννη για τη διάσωση των αρχείων του ᾽21, in Aa. Vv., Γιάννης Βλαχογιάννης. Α´ Συμπόσιο Ναυπακτιακής Λογοτεχνίας, Nàfpaktos, 18-19-20 November 1994, Athens 1995 [= Ναυπακτιακά 7], pp. 133-143.

Vlachojannis 1895 = J. Vlachojannis, Ἱστορικὰ ζητήματα, 1: Ὀδυσσεὺς Ἀνδροῦτσος, Athens 1895.Vlachojannis 1901 = J. Vlachojannis, Ἀρχεῖα τῆς Νεωτέρας Ἑλληνικῆς Ἱστορίας, I: Ἀθηναϊκὸν Ἀρχεῖον, Athens 1901.