OK, I’ll strike a more sober note today. Recently, the upheaval of higher education funding and student fees in the UK (where I am employed) has caused a great deal of discomfort (even the potential for sore egos, although misery always loves company). The arts and humanities are being forced to defend themselves once again.

Some academic critics have taken a hard stance against the “usefulness” or “impact” of the arts and humanities, on the grounds that what makes you free (or a good citizen, or a morally virtuous person, etc.), which is what the arts and humanities education does, cannot be calculated on a spreadsheet or counted with beans. (A Pythagorean might dispute the latter claim, that is, if beans really are souls.) Recently, at a conference hosted at the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities, entitled “Why Humanities?”, political philosopher Quentin Skinner in a paper called “Why the history of philosophy?”, responded in a distinctly different way: the history of philosophy is indeed useful and has external value for large parts of society in ways that everyone in society can see. His evidence? Philip Pettit’s apparently ongoing advisement of Zapatero’s Spanish Government on new government policy regarding democracy and republican thought.

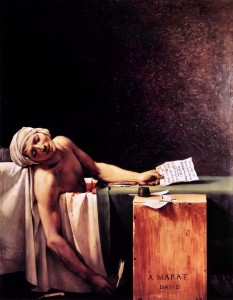

Having a philosopher as a political advisor is an ancient tradition, but I’m not so sure it has always worked to the benefit of the philosopher. Pythagoras is said to have arrived in Croton from Samos and to have advised the elders and youth on matters ethical and political; the old-money aristocrats ran him out of town. Plato tried to educate the young king of Syracuse Dionysius II in the ways of the philosopher-king; Dionysius Tyrannical put him in the clink. Seneca guided a young Nero from youth in the ways of Stoic philosophy; Nero Debauched forced his teacher to commit suicide.

Time and time again in Greco-Roman history, a leader will initially welcome a philosopher with open arms, only to inevitably tire of the philosopher and throw him to the lions. Plato elegantly describes this in the myth of the Cave in the Republic (514a-517a); Orson Welles even more elegantly narrates the myth (with 70s cartoon Greek ephebes to boot!).

What is the point of my post today?

Hey Obama, give me a ring! I’m just down the road!