Persistent identifier: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:ChritiM.Aristotle_as_a_Name-giver.2018

In this survey an attempt is made to examine whether Aristotle’s approaches to language, as depicted in his theory and practice, can be paralleled with those that gave rise to the fundamental principles of cognitive linguistics, the field which concentrates on what happens in the human mind during the production and reception of language.

Since cognitive linguistics is still in the process of self-definition, for the purposes of this survey the following fundamental and generally accepted principles and concepts — common to many linguistic fields — are used as a theoretical background in discussing whether Aristotle treated language in what is called today a cognitive manner in his theory and practice:

- The conventional and symbolic function of language; language expresses and externalizes certain semantic contents that we have in our mind, by vocal sounds which can also be represented in a written form.

- It is from these semantic contents that meanings are assigned to things through words: our cognitive capacities elaborate the information that we receive into specific and defined mental entities which can be depicted in language.

- Language means interaction: each linguistic act consists in the production of an utterance by a human being, but this meaningful vocal sound is received and understood by another human being.

- In the above procedures of the production and reception of language, a crucial role is played by:

- Constructions, in the sense of conventional combinations of vocal sounds and meanings, which correspond to mental images, as was just pointed out in (b). Constructions present diversity as regards their complexity, ranging from prefixes/suffixes to complicated compositions. They are uttered by speakers and evoke meanings in the minds of listeners, according to the interactive character of language.

- Semantic frames: They are the conceptual contexts where constructions obtain their meanings. Each construction has to be contextualized in order to bear its meaning and it is always understood, because it is related to a certain context (e.g., the construction priest evokes the semantic frame of religion with participants such as church, mass, rituals, etc.).

In general terms, according to cognitive linguistics human beings exploit their current linguistic material in order to bring together ideas and concepts from different areas of experience, thus creating new concepts that can be put in new contexts and applied in new usages.

More specifically, regarding Aristotle I argue that:

- Aristotle’s views on the production and reception of language form an approach to semantics that could be treated from the perspective of cognitive linguistics;

- Aristotle’s specific treatment of language is obvious in his own name-assigning, if we examine the process that he seems to be following from the unnamed concepts that he examines to the linguistic utterances that he suggests, regardless of their grammatical/syntactic form.

Aristotle is probably the first thinker to concern himself with matters that today are addressed under the general rubric of cognitive linguistics. More specifically: i) his formulation of the line between non-mediated reflexive representation and mediated conventional signification in On Interpretation 16a4–9; ii) his belief in the universal and non-attached to a specific language character of mental states that are formed after perception, an approach which is far from any kind of linguistic determinism in the same passage; iii) his exploration of what happens in the mind during the reception of language, putting it side-by-side to cognition, as it is obvious from On Interpretation 16b18–19, the Posterior Analytics II.XIX, 100a4–8, the Physics VII.3, 247b10–14 and iv) his tendency to exploit the available linguistic material, in order to integrate new concepts into known conceptual contexts, summarize the basic results of the present research. In an attempt to venture some reflections about the cognitive aspect of Aristotle’s treatment of language, it can be said that his linguistic approaches both in his theory and practice remind us of foundational cognitive linguistic principles.

Nevertheless, his views on the production and reception of language do not receive the credit they deserve when examined exclusively from the densely written semantic passage in On Interpretation, however comprehensive it may be and regardless of its reasonable impact. It is a text that can be highlighted and completed — more than one might initially suppose — by Aristotle’s description of ‘to signify’ in the same treatise, as well as by the discussion of ‘familiarity’ and its necessity as regards name-giving in the Categories 7a5-7, where he suggests that we should invent names for unnamed subjects, on the condition that the new word is given oikeiôs. This means that established linguistic material should be used in name-giving, a material that the speakers are obviously familiar with. A more or less completed puzzle is thus displayed concerning Aristotle’s cognitive approach to language, as he is intimately interested in both sides of linguistic interaction, production and reception of language.

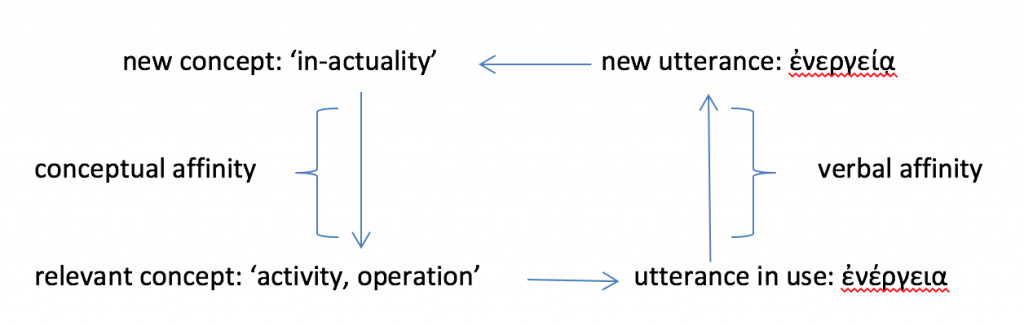

His concerns are traced in his practice of name-imposition too, a procedure which involves the use of conceptual and verbal proximities for the sake of familiarity in linguistic communication. New concepts emerge in Aristotle’s considerations from their relation to other concepts that already have names and form certain frames, where new concepts and new linguistic utterances can be integrated. The procedure that Aristotle seems to be following in his name-giving could be depicted as follows:

The cognitive approaches as described in (d) of the preliminary remarks are not absent from Aristotle’s name-giving in practice: he exploits the linguistic material that he has at his disposal to delve into the investigation of new concepts and he assigns new terms to them according to this material by suggesting constructions, i.e., units consisting of conventionally connected utterances and meanings, which are formed at various levels. Aristotle’s constructions depend on integration into particular semantic frames, in the sense of contexts consisting of semantically interrelated concepts. Therefore, new constructed relations between utterances and signifieds are suggested by him, i.e., the building of new semantic and verbal connections is encouraged on the basis of existing ones. Aristotle does not give any clues or instructions regarding the accurate circumstances under which a word could be reattributed, or certain grammatical forms, syntactic combinations etc., would be preferable in name-giving, because he seems interested in the familiarity of the result. This means that when we try to approach his linguistic suggestions in general terms, from the point of view of what is called today cognitive constructions, we would say that he proposes a variety of connections between utterances and contents, by choosing what he believes that suits him for each case, from his current linguistic usages.

Even if it is argued that Aristotle’s method is not strictly identified with a contemporary cognitive linguistic device or model, it can hardly be questioned that his treatment of the relation between concepts and utterances in his practiced name-giving evokes what is called today by cognitive linguists as constructions and semantic frames: the fact that Aristotle builds on known concepts and words is due to the respective semantic frames that are related to the content he wants to name. Therefore, previous relations between words and meanings are activated, so as to establish new ones and it is the speakers’ repeated experience of specific semantic frames that Aristotle counts on, when he selects a new term: he is based on the repeated named experience of his audience regarding certain named semantic contents and frames, in order to suggest new constructions that can be smoothly integrated into these frames. None of his linguistic suggestions can be considered as divergent from familiar conceptual and verbal contexts: new concepts that have to be named are always related to what could be called in contemporary cognitive linguistics as semantic frames and new concepts always participate in known and familiar contexts.

According to the above, there could be an argument opposing to E. Rosch’s belief about Aristotle’s (and ancient philosophers’ in general) concepts as arbitrary logical sets with clear-cut boundaries. Conceptual affinity is crucial for Aristotle to define and clarify a new concept, the definition of which is sealed with the new term that is verbally contingent on the name of the already defined and named notion.

It is not necessary to apply a specific pattern of cognitive linguistics to Aristotle’s theory of semantics and its respective practice, in order to affirm the cognitive aspect of both. If we consider cognitive linguistics as a flexible framework, as Geeraerts and Cuyckens suggest, we could detect in Aristotle the belief that language is a deposit helping him to organize pragmata/reality. It can hardly be questioned that basic cognitive principles — at least as they have been formed so far — are salient in Aristotle’s views on semantics, as well as in the process that he seems to be following when he suggests new terms, as it is evident that Aristotle is interested in rendering his linguistic suggestions cognitively functional. Since cognitive linguistics focuses on language as ordering, advancing and conveying information by emphasizing the conceptual and experiential basis of linguistic categories, it would not be difficult to argue that Aristotle’s theory and practice regarding name-assigning evokes such a framework: the philosopher treats language as depicting a certain potential for conceptualization and categorization, according to given linguistic usages. For Aristotle, language is intrinsically related to human cognitive capacities as is shown by the fact that he uses all the potential that his mother tongue provided him with to bring together ideas and concepts. The link between language and thinking as represented in his own linguistic behaviour demonstrates that he considered it fundamental to research, to learning about the data of experience, to categorizing them, but also to consolidating knowledge.

In an attempt to approach Aristotle by taking into account the apparatus of cognitive linguistics, the present study does not aim to prove that he had already conceived of its principles, but to reveal that contemporary interdisciplinary methods can provide classicists with new and inspiring tools when approaching ancient texts. Ιt is among the purposes of this article to underline that such an interpretation of ancient philosophical linguistic texts and the relevant practices of ancient authors can open a new window to the study of the history of linguistic ideas. New avenues of exploration can appear and thus, e.g., more specific research could involve the cognitive function of Aristotle’s classifications in his biological works, or the grammatical constructions that Aristotle seems to prefer in his name-impositions, depending on the character and subject matter of each treatise etc.; it may be hoped that, such sustained surveys are soon to follow.