Citation with persistent identifier:

Janse, Mark, & Joseph, Brian. “A New Historical Grammar of Demotic Greek: Reflections on the Κοινή Ελληνική in the 19th and 20th Centuries as Seen through Thumb’s Handbook of the Modern Greek Vernacular.” CHS Research Bulletin 2, no. 2 (2014). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:Janse_Joseph.What_Thumbs_Handbook_Tells_Us.2014

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ymyo3ZSadP0

Introduction

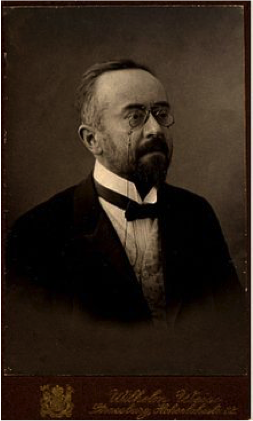

1§1 In 1895, the German Hellenist, Sanskritist, Indo-Europeanist, and general historical linguist Albert Thumb (1865–1915), known also for his more classically oriented scholarship both in Greek and in Sanskrit,[1] published his Handbuch der neugriechischen Volkssprache, an overview of the state of the Modern Greek language, with reference to then-current usage in what was emerging as a ‘standard’ form, to regional dialect forms, and to the general historical development of the language. A second edition in German came out in 1910, and a translated into English by Samuel Angus was published in 1912 under the title Handbook of the Modern Greek Vernacular.[2] There had been grammars of the modern language before Thumb, e.g. by Robertson (1818), by Sophocles (1857), and Wied (1893), among others, and Thumb himself begins his 1895 German edition by noting that “[t]he past century witnessed the publication of modern Greek grammars in large numbers”; further, some general scientific studies, e.g. Hatzidakis 1892, had appeared, but Thumb’s work, and especially its English version, made dialect material and historical information on Modern Greek that was based on careful philological and scientific linguistic principles available to a wider audience. It is a work that has stood up to the ravages of time and still in this day, some 120 years since its first appearance, it serves both the Neo-Hellenist and the Classical scholarly audience well.

1§1 In 1895, the German Hellenist, Sanskritist, Indo-Europeanist, and general historical linguist Albert Thumb (1865–1915), known also for his more classically oriented scholarship both in Greek and in Sanskrit,[1] published his Handbuch der neugriechischen Volkssprache, an overview of the state of the Modern Greek language, with reference to then-current usage in what was emerging as a ‘standard’ form, to regional dialect forms, and to the general historical development of the language. A second edition in German came out in 1910, and a translated into English by Samuel Angus was published in 1912 under the title Handbook of the Modern Greek Vernacular.[2] There had been grammars of the modern language before Thumb, e.g. by Robertson (1818), by Sophocles (1857), and Wied (1893), among others, and Thumb himself begins his 1895 German edition by noting that “[t]he past century witnessed the publication of modern Greek grammars in large numbers”; further, some general scientific studies, e.g. Hatzidakis 1892, had appeared, but Thumb’s work, and especially its English version, made dialect material and historical information on Modern Greek that was based on careful philological and scientific linguistic principles available to a wider audience. It is a work that has stood up to the ravages of time and still in this day, some 120 years since its first appearance, it serves both the Neo-Hellenist and the Classical scholarly audience well.

1§2 At the time that Thumb first began his account of Greek, i.e. in the late 19th century, Greece was still in the throes of the debate that had begun earlier in the century concerning the proper realization of an emblematic connection between a new Greek nation-state, formed in 1830 after the War of Independence from the Ottoman Empire, and ancient Greece. Viewed abstractly, the issue had to do with whether directly copying aspects of ancient Greece was the appropriate vehicle for demonstrating a connection between the modern Greek state and its historical antecedents or instead whether that connection was to be embodied through a recognition of natural processes of change acting on ancient institutions. Profound consequences ensued from this often very public discussion, ultimately affecting a number of areas of Greek scholarship[3] and of Greek life more generally.

1§3 One far-reaching effect on Greek life had to do with how this debate served in the shaping of the Greek language. Actually, as far as language was concerned, there were deeper chronological roots to this question, reaching back to the Atticistic movement of the Hellenistic era with its orientation towards the Classical form of the language and towards Classical models more generally. But in the aftermath of the formation of the Greek nation-state, the debate became institutionalized and eventually politicized in ways that it had not been before.[4] The Modern Greek language in the 19th and into the 20th centuries came thus to be pulled by warring language ideologies. This is the essence of the Greek ‘language question’ (γλωσσικό ζήτημα), which pitted the proponents of the consciously archaizing puristic katharevousa (καθαρεύουσα) variety of Greek against the advocates of the naturally evolved vernacular demotic (δημοτική) variety.

Thumb and the Language Question

2§1 Thumb was very much aware of the tensions that the Language Question posed for Greek and for Greece. And, he was very much aware of the difficulties associated with trying to pin down what the object of description was for the linguist/philologist aiming at an account of Modern Greek in the late 19th century. Yet at the same time, he felt comfortable in speaking of a common variety of Modern Greek that was available to most speakers. In his Foreword to the first German edition of his work (1895), Thumb states, quoting from Angus’s English translation, that his “Grammar … is above all a grammar of the vernacular Greek ‘Κοινή’” (p. xiv–xv). He then continues (p. xv):[5]

2§2 “The existence of a common and uniform type of the ‘popular speech’ (Volkssprache) is, of course, denied by some, it being maintained rather that beside the affected archaic written language there exist only dialects. The latter assertion I dispute, and I maintain that we are justified in speaking of a modern Greek ‘Κοινή,’ the language of the folk-songs in the form in which they are usually published being no more a specific dialect than that type of language of such popular poets as Christopoulos, Drosinis, Palamas, and many others, can be dubbed dialect. A perfect uniformity is admittedly not yet to be found, for just as sometimes on the one hand equally correct, i.e. equally wide-spread, forms occur side by side, so on the other many poets (as, e.g., Vilaras) manifest a marked propensity for dialect elements; yet in spite of all this we may speak of the ‘vernacular’ in contrast to the dialects. Many folk-songs in the course of extensive diffusion, passing from place to place, must have had their dialectic peculiarities reduced to a minimum, so that by a quite spontaneous process a certain average speech resulted. … This average popular speech—which readily arises particularly in the larger centres—serves as a means of communication which is intelligible not only in Patras, Athens, and Constantinople, but also in the country.”

2§3 What is particularly striking about this characterization from a modern perspective is that it is not unlike what is usually given as the definition of the object of description for contemporary accounts of Modern Greek; Mackridge (1985:12), for instance, defines “Standard Modern Greek,” the language he gives an account of in his book, as “the language normally written and spoken today by moderately educated Greeks in … urban centers,” i.e. cities such as Athens or Thessaloniki.[6]

2§4 Given the striking similarities between the abstractions of Thumb’s late-19th century Kοινή Eλληνική and Mackridge’s late-20th century “Standard Modern Greek,” it becomes interesting to examine specific forms to see how they measure up in various ways. Particularly telling are comparisons between Thumb’s Κοινή and the modern Standard, between these forms and Ancient Greek, and between these forms and regional dialects. In the following section, we explore a case study along these dimensions, and then discuss the lessons about the forces shaping the modern Standard that can be learned from the comparisons that this case study affords.

A Case Study

3§1 A most revealing case study comes from the nominal system and in particular from various forms to be found within the sub-classes of neuter nouns in Greek. In the class of neuter nouns in -μα, Ancient Greek had a singular nominative/accusative form in -μα and a genitive singular in -τος, and Standard Modern Greek (SMG) has a similar set of forms, as seen in (1):

| (1) | AG | SMG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sg | Nom/Acc | πρᾶγμα | πρά(γ)μα |

| Gen | πράγματος | πρά(γ)ματος | |

| Pl | Nom/Acc | πράγματα | πρά(γ)ματα |

| Gen | πραγμάτων | πρα(γ)μάτων | |

A comparison of the forms in (1) suggests that little has changed between Ancient Greek and SMG except for sound changes pertaining to vowel length, the realization of accent, and an apparent optional weakening of the sound represented by < γ > (velar stop [g] in Ancient Greek versus velar fricative [γ] or zero in the modern language). A consideration of Thumb’s Κοινή, abbreviated here as ‘EDG’, for ‘Early Demotic Greek’, as shown in (2), presents a very different picture, however:

| (2) | EDG | |

|---|---|---|

| Sg | Nom/Acc | πρᾶμα |

| Gen | πραμάτου | |

| Pl | Nom/Acc | πράματα |

| Gen | πραμάτω[7] | |

The differences between Thumb’s EDG and Ancient Greek on the one hand and between EDG and SMG are telling.

3§2 In particular, the Ancient Greek genitive singular form appears to be retained in SMG and yet it had already been replaced in EDG, where the ending < -ου > of the thematic (-ο-) stem nouns was generalized over the earlier ending < -ος >. Moreover, the accent placement in πραγμάτου is significant, as it has been pulled toward the end of the word by the ending < -ου >, as would be appropriate in such a genitive form with an original diphthong in the final syllable; this suggests that the generalization of < -ου > is a relatively old innovation, dating from a time when that accent shift, whether phonologically triggered as in Ancient Greek or morphologically triggered as in Post-Classical Greek, was still alive. It is revealing that these innovative forms are already attested in Medieval Greek, the only period in the history of the Greek language Thumb had not studied himself.

3§3 The other type of comparison mentioned above, namely between EDG and contemporary Greek regional dialects therefore becomes especially interesting, as forms equivalent to πραμάτου are to be found regionally in Greece today. For instance, several Asia Minor Greek dialects show a genitive πραμάτου (Pharasiot, Dawkins 1916:164) or πραμάτ’ (Cappadocian, Dawkins 1916:93), with the apostrophe here indicating that the high vowel < ου > has been deleted. It is telling that Dawkins, in his very brief description of ‑μα nouns in Silliot, simply states that “the -a neuters of the 3rd decl. are declined as generally in Modern Greek, e.g. ὅραμα, ὁραμάτου, ὁράματα” (1916:48—italics added).

3§4 There are a few other isolated neuters inflected like πράμα that show the same pattern of a Classical-like form in SMG but an innovative form with < -(τ)ου > in the genitive singular in EDG and regional dialects, and already attested in Late Medieval Greek (LMG):

- κρέας ‘meat’, gen. κρέατος (SMG) / κρεάτου (EDG & dialects), vs. AG κρέας, gen. κρέατος; LMG gen. κρέατος / κρεάτου

- άλας ‘salt’, gen. άλατος (learned), αλάτου (EDG & dialects), vs. AG ἅλας, gen. ἅλατος; LMG gen. ἅλατος / ἁλάτου

- γάλα ‘milk’, gen. γάλακτος (SMG), γαλάτου (EDG & dialects), vs. ΑG γάλα, gen. γάλακτος; LMG gen. γάλακτος / γαλάτου

Moreover, some neuter nouns in < -ο > are occasionally inflected in regional dialects like πράμα in the genitive, e.g. άλογο ‘horse’, gen. αλογάτου, pl. αλόγατα (already found in LMG, though analogy with πρόβατο ‘sheep’, gen. προβάτου, pl. πρόβατα, is possible for this word).

3§5 Overall, then, Thumb’s EDG forms for these neuter nouns are more closely aligned with present-day regional usage while the SMG forms are more closely aligned with Classical forms, even down to the possible presence of < -γ- > in πρά(γ)μα.

Explaining the Difference between AG and EDG and between EDG and SMG

4§1 The comparisons in section 3 thus lead to the question of what happened between Ancient Greek and the Thumb-era EDG and between EDG and the present-day Standard form of the language. It is reasonable to assume here that EDG is the predecessor of, the linguistic antecedent to, SMG, but the seeming ‘reversion’ to ancient forms in SMG demands an explanation. It is here that the recognition of Puristic pressures gives a basis for understanding these developments. In particular, noun paradigms such as that of πρά(γ)μα or κρέας were affected by a wave of Purism, the equivalent of a modern-day Atticism, that successfully led to re-shaping of system according to ancient patterns as far as Standard/Κοινή is concerned. But regional dialects, which for Thumb’s EDG were part of the general mix, but which in the prevailing Puristic ideology of the day were considered to be somehow beside the point, were left out of the re-shaping process, aimed as it was on the emerging ‘standard’ usage. That movement forced some forms, such as the genitives, singular πραμάτου and plural πραμάτω, to the peripheries of the contemporary linguistic scene, surviving only in regional dialects.

Conclusion

5§1 There are several interesting observations to make based on this comparative exercise involving Ancient Greek, Early Demotic Greek, Standard Modern Greek, and the contemporary regional dialects.

5§2 First, one result is that the regional dialects are the place where innovative forms occur, while the standard language is conservative. But the conservatism of SMG is really only artificial, due to what we might refer to as language engineering, the somewhat conscious re-shaping of Kοινή Eλληνική in the direction of Classical Greek, away from the innovative form that it had taken due to organic, natural paths of development. This is the reverse of what one often thinks of in connection with regional dialects, in that regional dialects in many situations involving other languages show archaisms and retentions whereas a standard form of the language shows innovation. For instance, in American English, the older construction with a’ and a present participle, such as John is out a’ huntin’ survives in regional (e.g. Appalachian) usage but is not current in Standard American English usage; so too with the double modal construction, e.g., It might could be the case, one finds it regionally restricted (mostly Midwest and South); and two older English constructions, so-called ‘double negation’ as in I can’t get no satisfaction, and the co-occurrence of a fronted ‘WH’ (question-like) word with that as in I don’t know why that he left me, are sociolectally restricted, found in the usage of speakers at the lower end of the socioeconomic scale.[8]

5§3 Beside the lesson to be learned from this about the role that linguistic purism, the καθαρεύουσα side of the γλωσσικό ζήτημα, played in shaping Modern Greek in the 20th century, there is also an important methodological point to be made here for historical linguistics and the study of language change. In particular, if all we had were Ancient Greek and Standard Modern Greek, and thus only a comparison of πράγματος and πρά(γ)ματος for the genitive singular, we would be justified in saying that very little had changed in that area of grammar; it is only when Thumb’s Early Demotic Greek and modern regionalisms are taken into account that the full picture emerges, as confirmed actually by Late Medieval Greek,[9] namely it is not that SMG has been stable relative to Ancient Greek, but rather that the vernacular forms—and πρά(γ)ματος today truly is vernacular, used by millions of Greek speakers in everyday interactions that do not smack of Purism at all—have undergone waves of reshaping by natural analogical mechanisms and also by the sociolinguistic intervention of Purism. Thus we can never take developments over long periods of time at face value but always need to view them in their full social context.

Bibliography

Brugmann, K. 1913. Griechische Grammatik. Vierte vermehrte Auflage bearbeitet von Albert Thumb. München.

Buck, C. D. 1914. Review of Handbook of the Modern Greek Vernacular by Albert Thumb. Classical Philology 9:85–96.

Dawkins, R. M. 1916. Modern Greek in Asia Minor. Cambridge.

Garantoudis, E. 1989. Aρχαία και νέα ελληνική μετρική. Ιστορικό διάγραμμα μιας παρεξήγησης. Padua.

Gignac, F. T. 1976. A Grammar of the Greek Papyri of the Roman and Byzantine Periods. Vol. I: Phonology. Milan.

Hatzidakis, G. 1892. Einleitung in die neugriechische Grammatik. Leipzig.

Herzfeld, M. 1982. Ours Once More: Folklore, Ideology, and the Making of Modern Greece. Austin.

Joseph, B. D. 1985. “European Hellenism and Greek Nationalism: Some Effects on Greek Linguistic Scholarship.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 3:87–96.

Mackridge, P. 1985. The Modern Greek Language: A Descriptive Analysis of Standard Modern Greek. Oxford.

———. 2011. Language and National Identity in Greece, 1766–1976. Oxford.

Mayser, E. 1970. Grammatik der griechischen Papyri aus der Ptolemäerzeit. Bd. I: Laut und Wortlehre. I. Teil: Einleitung und Lautlehre. 2. Aufl. bearb. von Hans Schmoll. Berlin.

Meillet, A. 1912–1913. Brugmann-Thumb: Griechische Grammatik. Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris 18, p. ccxxxvi.

Robertson, H. 1818. A concise grammar of the Modern Greek language, chiefly composed form the ‘Nova methodus’, &c., of Father Thomas; to which are annexed, phrases and dialogues on the most familiar topics, with extract from Romaic authors. London.

Schwyzer, E. 1939–1950. Griechische Grammatik. Auf der Grundlage von Carl Brugmanns Griechische Grammatik. München.

Sophocles, E. 1857. Romaic, or Modern Greek grammar. Boston.

Thumb, A. 1895. Handbuch der neugriechischen Volkssprache: Grammatik, Texte, Glossar. Strassburg. 2nd ed. 1910. Trans. Samuel Angus, Handbook of the Modern Greek Vernacular: Grammar, Texts, Glossary, Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1912.

———. 1901. Die griechische Sprache im Zeitalter des Hellenismus. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Beurteilung der Κοινή. Strassburg.

———. 1905. Handbuch des Sanskrit. Eine Einführung in das sprachwissenschaftliche Studium des Altindischen. Heidelberg.

———. 1915. Grammatik der neugriechischen Volkssprache. Berlin. 2nd rev. ed. 1928, rev. Johannes E. Kalitsunakis.[11]

Wied, K. 1893. Praktisches Lehrbuch der neugriechischen Volkssprach für den Schul- und Selbstunterricht. Vienna.

[1] He was the author, for instance, of Die griechische Sprache im Zeitalter des Hellenismus (Thumb 1901) and Handbuch der griechischen Dialekte (Thumb 1909), and editor of the 4th edition of Brugmann’s Griechische Grammatik (Brugmann 1913), which was the basis for Schwyzer’s Griechische Grammatik (Schwyzer 1939–1950). Meillet (1912–1913) referred to it as Brugmann-Thumb’s Griechische Grammatik. Among Thumb’s Sanskritic works, especially noteworthy is Handbuch des Sanskrit (Thumb 1905).

[2] Thumb also wrote a short grammar of the Modern Greek Vernacular for the Sammlung Göschen (Thumb 1915).

[3] See Herzfeld 1982 on the effects of this debate on Modern Greek folklore studies, and Garantoudis 1989 on how it affected the realization of Greek metrics in modern renditions of ancient poetry and drama. Joseph 1985 discusses examples of ideologically driven etymologizing among Greek scholars.

[4] See, for instance, Mackridge 2011 on this issue.

[5] Angus calls attention here to his translation of Thumb’s ‘Volkssprache’ as ‘popular speech’ even though he gives ‘vernacular’ as the translation of this German term elsewhere (e.g. in the title of the book).

[6] Of course, it is only because of external political events of the 20th century that Constantinople would not figure in such a characterization in the present day.

[7] The genitive plural form πραμάτω shows the loss of the final nasal < ν > which is already well attested in the Ptolemaic (Mayser 1970:169–171) and Roman and Byzantine papyri Gignac 1976:111–114). For many nouns, Thumb gives the genitive plural with variants in -ων and/or -ωνε, but does not give such variants for πρᾶμα. We cannot tell if he was just being inconsistent or if he was reporting what amounts to lexical-item by lexical-item variation. We are inclined to see the -ων forms as involving learned influence and the ‑ωνε as taking over (and generalizing) an initial ε- from a following word to protect a weak final nasal.

[8] Both double negation and WH-word-plus-that were common in earlier stages of English; cf. for the latter, the first line of the Canterbury Tales, Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote … “When April with its sweet showers.”

[9] Following up on Buck’s (1914) suggestions for a third edition of Thumb’s Handbook, it is our intention, as we re-work Thumb, to include more historical evidence, particularly from Late Medieval Greek, and restrict the dialectal evidence to what is relevant for Early Demotic Greek, thus excluding more exotic variants.

[10] Seated left to right: Albert Thumb (1865–1915), Giorgios Hatzidakis (1848–1941), Berthold Delbrück (1842–1922); standing left to right: Paul Kretschmer (1866–1956), Max Vasmer (1886–1962), Hubert Pernot (1870–1956), August Heisenberg (1869–1930).

[11] The third edition was published under Kalitsunakis’s name in 1963.