Citation with persistent identifier:

Cazzato, Vanessa. “Reclining with Callinus and Tyrtaeus: Martial Elegy in the Symposion.” CHS Research Bulletin 2, no. 2 (2014). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:CazzatoV.Reclining_with_Callinus_and_Tyrtaeus.2014

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5RLgqxNRfhA

§1 That martial elegy, like all shorter elegy, belonged to (some form of) the symposion has become a matter of scholarly orthodoxy since Ewen Bowie formulated his powerful arguments to this effect almost thirty years ago.[1][2] More recently, Elizabeth Irwin has offered a thorough analysis of the social function of martial elegy in the symposion within a historicist framework.[3] What remains to be explained fully is precisely how these poems ‘worked’ as poetry in a sympotic context. The present essay aims to begin to provide such an explanation; it does so by building on Irwin’s interpretation of the poems as epic role-play and comparing the poetic strategies of Callinus fr. 1 and Tyrtaeus fr. 10 to some rhetorical strategies characteristic of the symposion more generally, particularly as instanced by the iconography of sympotic pottery.

§2 Irwin’s argument is that the sympotic world implied as performance context fulfils a narrative function, as the status and privileges enjoyed by the closed group of participants are legitimized by their martial prowess. The symposiasts cast themselves in the role of the Homeric heroes, and the meal they enjoy is a rightful reward for their deeds in war. This notion of epic role-play receives support from Andrew Morrison’s observations on the language employed by the ‘narrator’ of martial elegy; as he remarks, the pervasiveness in martial elegy of evaluative terms such as statements about what is τιμῆεν…καὶ ἀγλαόν (Callinus fr. 1 line 6) or καλόν (Tyrtaeus fr. 10 line 1) “reveal[s] that the narrator in these elegies regularly employs what are speech-words in Homer.”[4] If this distinction between narrator speech and character speech in epic poetry was traditional and sufficiently marked to be felt by the performers and their audience, then in reciting exhortatory elegy at the symposion the symposiasts are addressing each other in the language of the heroes of these poems. They are in a sense in a sense imagining themselves as characters of the epic poems.[5]

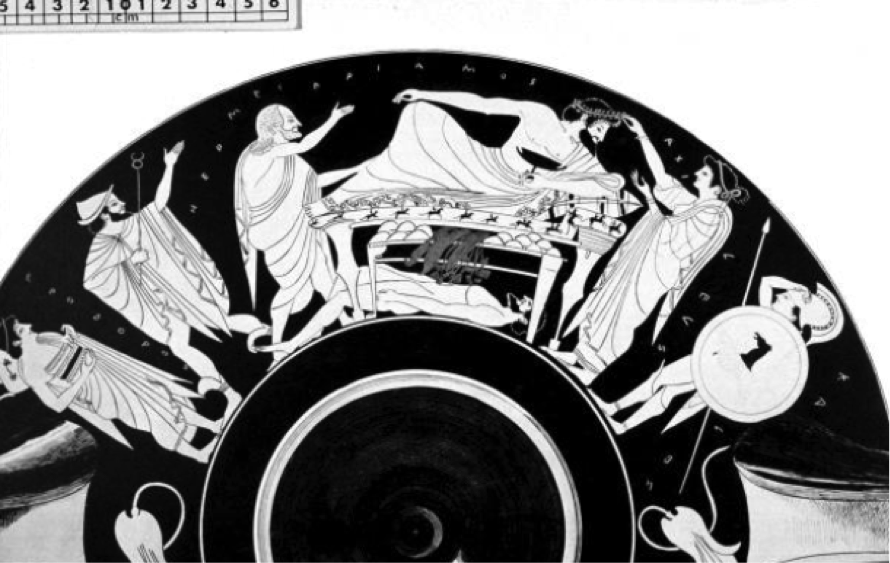

§3 What we have in our elegies of martial exhortation, then, is a pointed interaction between the heroic world conjured up by the content of the poetry and the sympotic world which is presupposed by its performance. Such interactive ‘rhetorical’ strategy can be seen in the pottery of the symposion, too; a selection of visual examples will help bring into focus some of the poetic conceits of our sympotic martial elegies. These visual parallels from sympotic pottery act as helpful analogies, but also as supporting evidence for the kinds of aesthetic conceits which would have been at home in the context of performance of our martial elegies. Though the evidence of the pottery dates to a later period than that in which Callinus and Tyrtaeus composed and emerges from a different geographical region, it shared the sympotic context of the martial elegies for a large part of their transmission, and so it must count as evidence for their continued relevance in reperformance which allowed them to survive long enough for them to be preserved by Lycurgus and Stobaeus. On the pottery, then, we see the sympotic context being made instrumental to the representation and adding new layers of meaning to an epic scene in the common iconographical schema of the ransom of Hector’s body. An Athenian red-figure cup by the Oltos painter, dated to around 500 BC, (Figure 1, below) offers a visual account of this episode which differs in a number of ways from the Iliadic story.[6] Instead of being seated in the heroic manner Achilles is portrayed reclining just like a symposiast in standard sympotic ‘genre’ scenes[7]—a posture which mirrors that of the user of the cup and makes the representation rebound outward to the context of reception in a familiar procedure of sympotic pottery as well as poetry. Here, this procedure is emphasized by the fact that Achilles holds in his right hand, starkly silhouetted against his chest, a cup of the same shape and of the same dark colour as the cup on which the scene is painted; this draws attention to the game of mise en abîme and thereby reinforces the invitation to the user of the cup to identify himself with the symposiast Achilles. A further departure form the Iliadic story lies in the fact that the body of Hector is visible, instead of being kept out of view on Achilles’ order so as to spare the old man the awful sight (Iliad XXIV 582–586). The placing of Hector’s dead body underneath that of the reclining Achilles is the standard compositional scheme for painted scenes of the Ransom, but it is particularly striking here given the amount of space at the artist’s disposal (the scene continues on the other side of the cup, where a procession of gift-bearers is shown). This composition reinforces the contrast between the living body of the banqueting wrathful Achilles and the prostrate body of the slain warrior Hector, and in so doing adds further connotations to the sympotic posture. Achilles’ decision to withdraw from battle at his own will is juxtaposed with Hector’s dutiful self-sacrifice and these two moral stances are illustrated by the hero’s posture, lying at the symposion and lying in death respectively. We will see that this contrast, too, finds a direct counterpart in the exhortations of Callinus and Tyrtaeus. But above all the viewer-drinker of this cup (and numerous other similar ones) is actively invited to draw a comparison between himself and a heroic character of epic. He is also encouraged to draw a connection between the sympotic world he inhabits and the epic world within the representation, and the boundaries between the two worlds are to some extent blurred. This is a precise visual analogue of what we see in the exhortatory elegies of Callinus and Tyrtaeus: the sympotic audience is presented with an epic scene of sorts—an example of paradigmatic epic behaviour expressed in epic language—and encouraged to take a stance and, furthermore, to assume through role-playing the persona of the exemplary epic hero. And in the poetry as on the pottery, the sympotic world and the epic world are blended or made to interact so that the imaginary Iliadic world can be made explicitly to inform the sympotic ‘here and now’.

§4 The significance of the depiction of Achilles as a symposiast should not be underestimated. As Robin Osborne has argued persuasively, cups self-reflexively depicting the symposion were an important part of sympotic aesthetics and their users were encouraged to compare the symposion around them (and their behavior within it) with that represented on the cups from which they were drinking: “… the drinking viewer is encouraged to interact with the images and challenged by them to take a stand on the sort of identity he will project.”[8] In just the same way, the speaker of our elegies challenges his drinking audience to take a stand and react in the appropriate way. He casts them in a represented heroic world and thus forces upon them a moral choice which is made perspicuous by the implications of this heroic fictional world. For an epic fictional world tends to operate according to certain rules: heroes, on the whole, fight valiantly, in just the same way as e.g. in a bucolic fictional world shepherds pine for love. This is the case even though the epic world of Homer’s Iliad is rather more complicated. There, characters tend to question the terms of the code of honor which is on the other hand presented as entirely straightforward in our elegiac exhortations. But it is precisely the tension with a more general order of things that lends the Iliad its special dramatic force. The epic world of exhortatory elegy, on the other hand, is a selective and simplified epic world, one more suited to act as an exemplary paradigm than the more complicated world of epic.

§5 On the Oltos cup as in the poetry (see Callinus fr. 1 W2: ‘you are reclining when you should be fighting’), there is a disjunction between the spheres of war and of the symposion. Achilles’ story revolves around the refusal to fight at the right time. Achilles is also the hero for whom the choice of glory bought through death in the battlefield presents itself in an especially acute manner. On the cup, he is shown turning away from Priam: instead of responding to the sorrowful old man, Achilles, delicately holding his cup, turns his attention to a female character who is placing a garland on his head.

§6 So several features of this visual representation which mixes sympotic with epic martial themes are particularly relevant in relation to our poems. These are the encouragement to take a stance in relation to epic behaviour, the implied contrast between reclining in the symposion and being prostrate in death, and (its corollary) a contrast between shrinking from danger on the one hand and choosing war and self-sacrifice on the other; and finally, an overlapping of the mental worlds of the symposion and of epic warfare. We may now turn to Callinus fr. 1 W2, to see some of these features in play.[9]

μέχρις τέο κατάκεισθε; κότ’ ἄλκιμον ἕξετε θυμόν,

ὦ νέοι; οὐδ’ αἰδεῖσθ’ ἀμφιπερικτίονας

ὧδε λίην μεθιέντες; ἐν εἰρήνηι δὲ δοκεῖτε

ἧσθαι, ἀτὰρ πόλεμος γαῖαν ἅπασαν ἔχει

………

καί τις ἀποθνήσκων ὕστατ’ ἀκοντισάτω. 5

τιμῆέν τε γάρ ἐστι καὶ ἀγλαὸν ἀνδρὶ μάχεσθαι

γῆς πέρι καὶ παίδων κουριδίης τ’ ἀλόχου

δυσμενέσιν· θάνατος δὲ τότ’ ἔσσεται, ὁππότε κεν δὴ

Μοῖραι ἐπικλώσωσ’. ἀλλά τις ἰθὺς ἴτω

ἔγχος ἀνασχόμενος καὶ ὑπ’ ἀσπίδος ἄλκιμον ἦτορ 10

ἔλσας, τὸ πρῶτον μειγνυμένου πολέμου.οὐ γάρ κως θάνατόν γε φυγεῖν εἱμαρμένον ἐστὶν

ἄνδρ’, οὐδ’ εἰ προγόνων ἦι γένος ἀθανάτων.

πολλάκι δηϊοτῆτα φυγὼν καὶ δοῦπον ἀκόντων

ἔρχεται, ἐν δ’ οἴκωι μοῖρα κίχεν θανάτου, 15

ἀλλ’ ὁ μὲν οὐκ ἔμπης δήμωι φίλος οὐδὲ ποθεινός·

τὸν δ’ ὀλίγος στενάχει καὶ μέγας ἤν τι πάθηι·

λαῶι γὰρ σύμπαντι πόθος κρατερόφρονος ἀνδρὸς

θνήισκοντος, ζώων δ’ ἄξιος ἡμιθέων·

ὥσπερ γάρ μιν πύργον ἐν ὀφθαλμοῖσιν ὁρῶσιν· 20

ἔρδει γὰρ πολλὼν ἄξια μοῦνος ἐών.How long will you lie idle [or recline]? When will you young men

take courage? Don’t our neighbours make you feel

ashamed, so much at ease? You look to sit at peace,

but all the country’s in the grip of war!

……………..

and throw your last spear even as you die.

For proud it is and precious for a man to fight

defending country, children, wedded wife

against the foe. Death comes no sooner than the Fates

have spun the thread; so charge, turn not aside,

with levelled spear and brave heart behind the shield

from the first moment that the armies meet.A man has no escape from his appointed death,

not though his blood be of immortal stock.

Men sometimes flee the carnage and the clattering

of spears, and meet their destiny at home,

but such as these the people do not love or miss:

the hero’s fate is mourned by high and low.

Everyone feels the loss of the stout-hearted man

who dies; alive, he ranks with demigods,

for in the people’s eyes he is a tower of strength,

his single efforts worth a company’s.

The use of epic language conjures up a recognizably Iliadic world.[10] At the same time, the reference to the practice of reclining through the verb κατάκεισθε in the first line acknowledges the sympotic ‘here and now’ and includes the symposion in the ‘plot’ of a dramatic situation:[11] the addressees should be fighting instead of feasting. This opening (if indeed this is the beginning of the poem, but the vocative in the first pentameter makes it likely) is striking also for the unusual construction with the present, which is extremely rare.[12] This adds to a sense of actuality and reinforces the reference to the sympotic ‘here and now’.[13] In the heroic world this kind of epic exhortation evokes a battlefield as its setting, since that is where heroes are usually exhorted; a typical situation for such exhortation might be the famous appeal by Hector to the Trojans (Iliad XIX 494–499) quoted by Lycurgus (our source for Tyrtaeus fr. 10) as being one of the sections of Homer which spurred to glory the Greeks at Marathon, or the speeches at Iliad V 529–532 or XVII 227–228. The elaborate exhortation directed at Achilles in Iliad IX is a crucial exception: he might be regarded as an irregular symposiast, as he sits ruefully alone, lyre in hand. It may not be unwarranted to imagine some interaction in our elegy with the idea of trying to get Achilles to fight. This would draw on an unusual situation in the Iliadic story, but the pottery does make much of it in its insistence on the depiction of Achilles as a symposiast.

§7 The use of epic language and subject matter to create an exemplary heroic world which is fed into the sympotic ‘here and now’ comes into sharper focus when we look more closely at the internal articulation of the fragment. If we view the poem in light of Christopher Faraone’s theory on the stanzaic architecture of early Greek elegy we can distinguish two slightly different rhetorical ‘modes’.[14] Faraone’s argument is that early Greek elegy was composed in basic units of five couplets, and that in the particular case of martial elegy, there is a pattern of stanzas of exhortation which are more firmly rooted in the ‘here and now’ being alternated with more meditative stanzas. The argument is particularly difficult to apply to our fragment of Callinus given that there is a lacuna of an unknown number of lines after line 4, but there are nevertheless several traces of such stanzaic structuring. We have a discrete compositional unit corresponding to a meditative stanza in lines 12–21: here the couplets are more frequently end-stopped, and are stylistically more elaborate, there is a series of internal rhymes (lines 13, 19, 21) and spondaic first half-lines. These are regular features which, according to Faraone, generally mark out meditative stanzas from exhortatory stanzas. The latter, by contrast, tend to exhibit much more frequent run-over between couplets and to be more firmly rooted in the ‘here and now’. The first four lines, with their emphatic rhetorical questions, might then correspond to an exhortatory stanza (pace Faraone).[15] Lines 5–11 are also likely to belong to an exhortatory stanza: here the frequent run-over and the less elaborate rhetorical style bring these exhortatory sections closer to speech, especially in the staccato questions at the beginning of the fragment. The distinction between meditative and exhortative stanzas shows up the alternation between the evocation of a world as present on the one hand and the more detached comment on this world on the other hand. This seems to imply two different representational modes. In the first mode—the exhortatory—the element of role-playing is more marked. In the second mode—the meditative—while the role-playing is still a factor (the language used continues to be that of epic warriors reflecting on their fate), it seems much less obtrusive, since general reflections about life and death are easily accommodated to the world of the symposion. In the first mode we are as if ‘dropped’ into a fictional world of the epic battlefield; in the second mode we take a step back and contemplate it. The ‘interactive’ aesthetic identified at the outset, one which breaks down the interface between the represented epic world and the sympotic world in which it is beheld, is thus effectively modulated in the alternation between conjuring up an epic world and inviting the audience to relate to it in a more personal way.

§8 The same effects we have remarked in Callinus are discernible in a more developed form in Tyrtaeus fr. 10 W2.

τεθνάμεναι γὰρ καλὸν ἐνὶ προμάχοισι πεσόντα

ἄνδρ’ ἀγαθὸν περὶ ἧι πατρίδι μαρνάμενον·

τὴν δ’ αὐτοῦ προλιπόντα πόλιν καὶ πίονας ἀγροὺς

πτωχεύειν πάντων ἔστ’ ἀνιηρότατον,

πλαζόμενον σὺν μητρὶ φίληι καὶ πατρὶ γέροντι 5

παισί τε σὺν μικροῖς κουριδίηι τ’ ἀλόχωι.

ἐχθρὸς μὲν γὰρ τοῖσι μετέσσεται οὕς κεν ἵκηται,

χρησμοσύνηι τ’ εἴκων καὶ στυγερῆι πενίηι,

αἰσχύνει τε γένος, κατὰ δ’ ἀγλαὸν εἶδος ἐλέγχει,

πᾶσα δ’ ἀτιμίη καὶ κακότης ἕπεται. 10εἰ δ’ οὕτως ἀνδρός τοι ἀλωμένου οὐδεμί’ ὤρη

γίνεται οὔτ’ αἰδὼς οὔτ’ ὀπίσω γένεος.

θυμῶι γῆς πέρι τῆσδε μαχώμεθα καὶ περὶ παίδων

θνήισκωμεν ψυχ<έω>ν μηκέτι φειδόμενοι.

ὦ νέοι, ἀλλὰ μάχεσθε παρ’ ἀλλήλοισι μένοντες, 15

μηδὲ φυγῆς αἰσχρῆς ἄρχετε μηδὲ φόβου,

ἀλλὰ μέγαν ποιεῖτε καὶ ἄλκιμον ἐν φρεσὶ θυμόν,

μηδὲ φιλοψυχεῖτ’ ἀνδράσι μαρνάμενοι·

τοὺς δὲ παλαιοτέρους, ὧν οὐκέτι γούνατ’ ἐλαφρά,

μὴ καταλείποντες φεύγετε, τοὺς γεραιούς. 20αἰσχρὸν γὰρ δὴ τοῦτο, μετὰ προμάχοισι πεσόντα

κεῖσθαι πρόσθε νέων ἄνδρα παλαιότερον,

ἤδη λευκὸν ἔχοντα κάρη πολιόν τε γένειον,

θυμὸν ἀποπνείοντ’ ἄλκιμον ἐν κονίηι,

αἱματόεντ’ αἰδοῖα φίλαις ἐν χερσὶν ἔχοντα – 25

αἰσχρὰ τά γ’ ὀφθαλμοῖς καὶ νεμεσητὸν ἰδεῖν,

καὶ χρόα γυμνωθέντα· νέοισι δὲ πάντ’ ἐπέοικεν,

ὄφρ’ ἐρατῆς ἥβης ἀγλαὸν ἄνθος ἔχηι,

ἀνδράσι μὲν θηητὸς ἰδεῖν, ἐρατὸς δὲ γυναιξὶ

ζωὸς ἐών, καλὸς δ’ ἐν προμάχοισι πεσών. 30ἀλλά τις εὖ διαβὰς μενέτω ποσὶν ἀμφοτέροισι

στηριχθεὶς ἐπὶ γῆς, χεῖλος ὀδοῦσι δακών.For it is a fine thing to lie fallen in the front line,

a brave man fighting for his fatherland,

and the most painful fate’s to leave one’s town

and fertile farmlands for a beggar’s life,

roaming with mother dear and aged father,

with little children and with wedded wife.

He’ll not be welcome anywhere he goes,

bowing to need and horrid poverty,

his line disgraced, his handsome face belied;

every humiliation dogs his steps.This is the truth: the vagrant is ignored

and slighted, and his children after him.

So let us fight with spirit for our land,

die for our sons, and spare our lives no more.

You young men, keep together, hold the line,

do not start panic or disgraceful rout.

Keep grand and valiant spirits in your hearts,

be not in love with life—the fight’s with men!

Do not desert your elders, men with legs

no longer nimble, by recourse to fight:it is disgraceful when an older man

falls in the front line while the young hold back,

with head already white, and grizzled beard,

gasping his valiant breath out in the dust

and clutching at his bloodied genitals,

his nakedness exposed: a shameful sight

and scandalous. But for the young man, still

in glorious prime, it is all beautiful:

alive, he draws men’s eyes and women’s hearts’

felled in the front line, he is lovely yet.Let every man then, feet set firmly apart,

bite on his lip and stand against the foe.

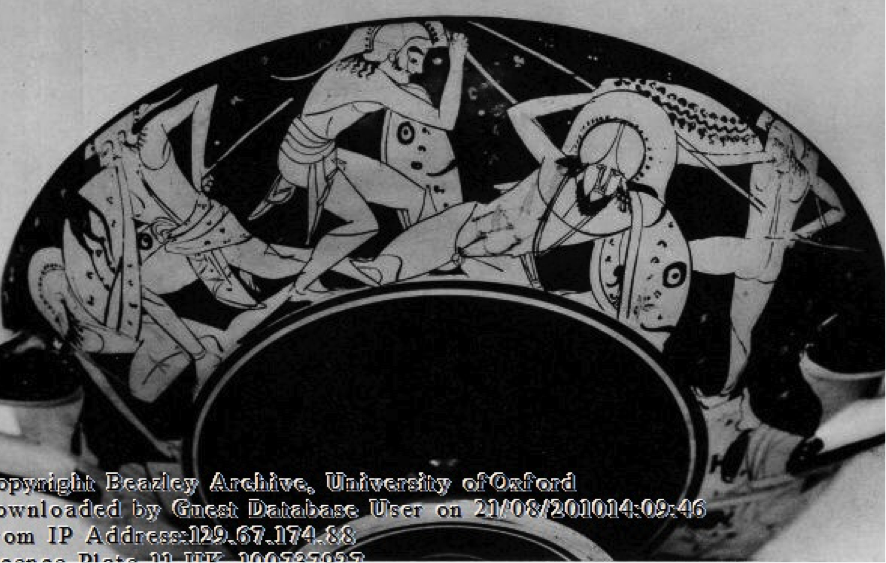

If we grant that the poem was performed at a symposion, then here too it becomes natural to contrast the body of the dead warrior (explicit) with that of the reclining symposiast (implicit). The embodied presence of the reclining singer and audience finds a counterpart in the vivid and almost voyeuristic description of the dead warriors in lines 21–30. Here we are presented with two different bodies—the young and the old warrior—symmetrically juxtaposed and conjured up as a sight to behold in order to make a moral choice. This direct appeal to the symposiast to measure himself up against the heroic slain hero on the battlefield also finds a parallel on painted pottery in an Athenian red-figure cup discussed at some length by Robin Osborne, to whom the present treatment in indebted (Figure 2, below).[16] The cup is self-reflexive in that on one side a symposion is represented, while beneath the scene runs a band with various vessels and other sympotic equipment silhouetted. The other side depicts in a “broad, but clear, compositional ‘rhyme’,”[17] a scene of warriors fighting. The bodies are ‘blocked’ in corresponding ways across the two scenes, thus inviting a comparison between the symposion and the battlefield, and in turn between the symposion on the cup and that without it—the symposion in which the viewer is participating. The collapsed warrior in the battle scene (the ‘reclining’ one, corresponding to the main symposiast on the other side of the cup) looks out of the picture and engages the gaze of the viewer directly, thus breaking out of the picture plane. It is the beautiful body of the prostrate warrior (in full manly beauty, like Tyrtaeus’) that is looking out at the viewer. Human figures are very rarely shown looking at the viewer in Greek vase painting; when they are it is to striking and purposeful effect.[18] It is often the case that humans depicted frontally are in circumstances which cause them to abstract themselves from their present situation, which may be one of extreme effort, Dionysiac frenzy, or, as in our case, imminent death.[19] At the moment of dying, the warrior is shown withdrawing from eye-contact with his fellow warriors, thus contravening the usual iconographic rule of profile representation. In this way, he cuts himself off from intercourse with the other characters in the scene; he seems to step out of the world of the representation by looking directly out at the viewer. In a similar way, Homer ‘apostrophizes’ a warrior at the moment of death (e.g. Melanippus at Il. 15.582, and the device then is put to maximum use to evoke the death of Patroclus even before it happens at 16.692–693; 787; maybe 788, depending on how we translate τοι; 813; 843). This interaction between poet and character, too, is a trespassing across the representational plane. The apostrophe parallels the conceit used in the vase where the warrior is unexpectedly made to look out of the vase directly at the viewer at the moment of death so that there is a direct connection between the character within the fiction and the audience without.[20] And in just the same way, in the sympotic context of our poems of martial exhortation, the role-play instigated by the use of epic language and imagery creates an open channel between the represented world of the warriors and the world of the ‘here and now’ outside the representation. This encourages an almost emotive connection with the dying warriors which acts as a prompt towards the correct kind of moral behaviour.[21]

§9 In Tyrtaeus’ poem, both meditative stanzas or sections (lines 1–10 and 20–30) are structured around the contrast between a good and a bad example: in the first the valiant warrior is contrasted with the craven one, in the last the old warrior is compared with the young warrior in death. In both cases the good and bad vignettes are held up as scenes to be beheld. In both cases the negative example is the more detailed and prominent. The exhortation in the middle stanza follows logically from these negative examples. Here again there is the same alternation as we have seen in the fragment of Callinus between acting in the marked sympotic world of martial feasting in the second stanza and contemplating an imaginative epic scenario in the first and third stanzas. The repeated contrast between good and bad and the consequent exhortation to do what is good bring out more forcefully the didactic stance of the speaking persona, and it is this that we will now examine as a possible further feature of the sympotic language game that is martial exhortation.

§10 The emphasis on the attractiveness of youth, to men and to women, with words of gazing and desire (ἐρατῆς in line 28, θηητός and ἐρατός in line 29) creates a challenging interaction with the sympotic world. The challenge is pressed to the end when the youth is καλός even in death. There is an interesting relation between the image of the old warrior in the meditative stanza and the deictic indications of age in the ‘here and now’. At lines 13–14, the poet uses the first person plural and includes himself in the exhortation, whereas at lines 15–16 and again in the final extant couplet at line 31 (assuming it belongs), he uses the second person plural. The poem, then, implies two kinds of addressees, the ‘young’ warriors and the ‘old’ (or ‘older’) warriors, and the speaker belongs to the latter group. The speaker of the fragments is addressing νέοι and marking himself off as an older man. This seems to be a generic trait shared with other kinds of sympotic poetry such as the political and erotic poetry of Theognis, and the erotic poetry of Anacreon and Mimnermus. It is likely that the exhortation directed at the νέοι is a generic convention. As Nicole Loraux has remarked, in a martial context νέοι (as opposed to ἄνδρες or γέροντες) are those who are being initiated into combat.[22] The use of this term suggests that what we have in our poems is not so much an exhortation to fight in a particular situation as an exemplary exhortation—it is an instance of the same sort of didactic sympotic stance as we see in elegy other than martial, most especially in Theognis. In fact, in a poem of Theognis (lines 549–554) which is clearly a sympotic utterance, addressed as it is to Cyrnus, we find a surprisingly close parallel to our martial exhortation:

ἄγγελος ἄφθογγος πόλεμον πολύδακρυν ἐγείρει

Κύρν’, ἀπὸ τηλαυγέος φαινόμενος σκοπιῆς. 550

ἀλλ’ ἵπποισ’ ἔμβαλλε ταχυπτέρνοισι χαλινούς·

δήιων γάρ σφ’ ἀνδρῶν ἀντιάσειν δοκέω—

οὐ πολλὸν τὸ μεσηγύ—διαπρήσσουσι κέλευθονThe voiceless messenger awakens woeful war,

Cyrnus, blazing forth from the lookout visible from afar.

Come now saddle up your swift-footed steeds:I think we’ll engage in battle with fierce men

they are not far—they are on the march.

Here, too, a dangerous circumstance of war is strikingly portrayed as present in the ‘here and now’, and Theognis directs his authoritative voice to his young companion to exhort him to action. This shows that there could be a remarkable continuity between the more overtly sympotic elegiac fragments and our fragments of martial exhortation.

§11 It is probable, then, that in our martial poetry, too, we witness a participant in the symposion taking on, as well as the persona of an epic hero, that of an older man addressing younger men. In this sense, the epic persona is modified to suit the setting of the symposion. In epic we do not get the distinction between younger and older fighters. There is the exception of Nestor and Antilochus, and we are also told that Patroclus is older than Achilles, but on the whole the generations are compressed in the epic cycle, and on the Iliadic battlefield heroes are all essentially of the same age—ἥλίκες.[23] On the other hand, the distinction between a younger and an older generation is, as we have seen, a key ingredient of the sympotic world. It corresponds to the distinction between erastes and eromenos in the erotic sphere. A visual counterpart of this is seen on pottery depicting the symposion, where bearded and beardless men are always seen side by side. The convention by which an older man’s didactic persona is adopted, then, may be regarded as another rule in the sympotic language game played out by the poems.

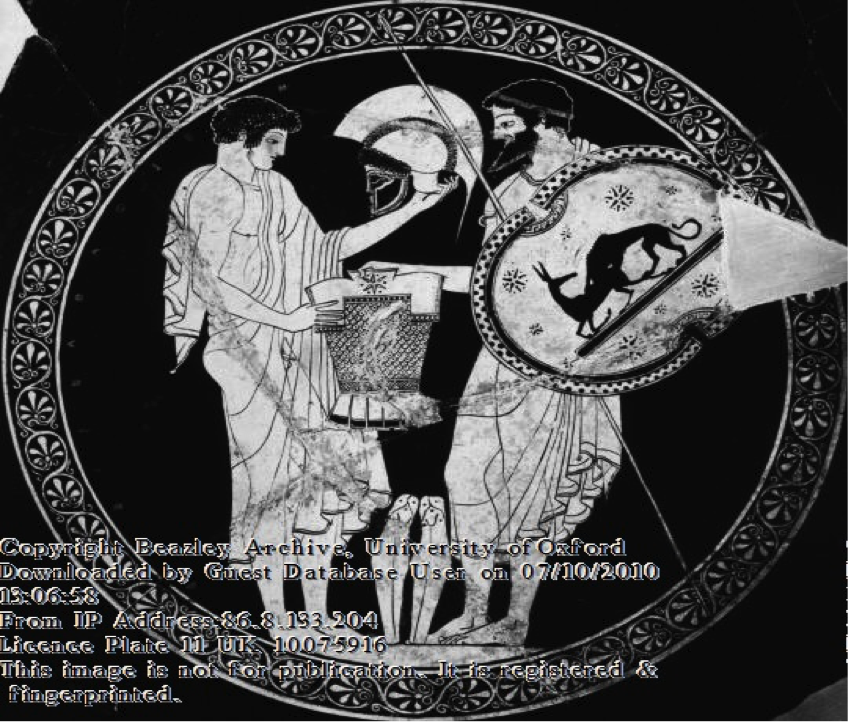

§12 In fact, a more specific visual analogy is found on vases depicting this didactic relationship in a specifically martial context. On a cup by Douris (Figure 3) the exterior depicts the fairly common scene of the quarrel over the arms of Achilles: the interior shows an older man handing to a νέος a similar (archaizing) armour to that seen in the mythological scene.[24] Here we see in action two aspects of the language game which we had observed in our martial exhortation. First of all, the cup replicates the poem’s martial didactic stance of an older man towards a νέος or νέοι. This reinforces our idea that such a set-up is a topos or ‘rule’ of a rhetorical strategy typical of the symposion. Secondly, we see replicated in the cup the idea of epic role-play in a sympotic setting; this is flagged by the archaizing armour, which links the exterior representation to the tondo. It is possible to construe the two characters in the tondo as Odysseus and Neoptolemus, but it is just as easy to construe them as the generic erastes and eromenos characters who are often depicted on sympotic pottery handing and receiving gifts. The drinker is made first to behold the mythological scene on the exterior, and then, on draining his cup, he is faced with another scene which relates the epic one to the ‘here and now’ of the sympotic situation in which he is participating. This relating of the epic world to that of the ‘here and now’ is played out in a strikingly similar fashion to what we have observed in our exhortatory fragments.

§13 These several similarities between the vases and the poems, then, suggest that some of the ploys we meet in poetry may fit into larger cultural patterns of comparison and contrast. Moreover, they add to the body of evidence testifying to that peculiar ‘interactive’ aesthetics first identified as being characteristic of the symposion in the pioneering work of Francois Lissarrague.[25] This is a more pervasive sympotic mindset than simply a playfulness such as we are accustomed to noticing in the more conspicuously witty fragments of e.g. Anacreon or the cups with visual puns; attentiveness to less overt instances proves rewarding. It is only in this context of an aesthetics of interaction across representational planes that our poems of martial exhortation, with all their serious political and moral import, can begin to be properly understood.

Bibliography

Adkins, A. W. H. 1977. “Callinus 1 and Tyrtaeus 10 as poetry.” HSCP 81:59–97.

Aloni, A. 2009. “Elegy.” In Budelmann 2009:168–188.

Bettini, M., ed. 1991. La maschera, il doppio e il ritratto. Bari

Berard, C., ed. 1989. A City of Images. Iconography and Society in Ancient Greece. Princeton.

Bowie, E. 1986. “Early Greek elegy, symposium and public festival.” JHS 106:13–35.

———. 1990. “Miles ludens? The problem of martial exhortation in early Greek elegy.” In Murray 1990:221–229.

Campbell, D. A. 1967. Greek Lyric Poetry. London.

Cingano, E. 2010. “Differenze di età e altre peculiarità narrative in Omero e nel ciclo epico.” In Cingano 2010:77–90.

Cingano, E., ed. 2010. Tra panellenismo e tradizioni locali: generi poetici e storiografia. Alessandria.

D’Agostino, B., and D. Ridgway, eds. Apoikia. Scritti in onore di Giorgio Buchner. Annali Istituto Orientale di Napoli, n.s. 1. Naples.

Dasen, V., and J. Wilgaux. 2008. Langage et métaphores du corps. Rennes.

Faraone, C. A. 2008. The Stanzaic Architecture of Early Greek Elegy. Oxford.

Frontisi-Ducroux, F. 1986. “La mort en face.” Metis I 2:197–218.

———. 1991. “Senza maschera né speccho: l’uomo greco e i suoi doppi.” In Bettini 1991:131–158.

Giuliani, L. 2013. Image and Myth. A History of Pictorial Narration in Greek Art. Chicago.

Griffin, J. 1986. “Homeric words and speakers.” JHS 106:36–57.

Hutchinson, G. O. 2010. “Deflected addresses: apostrophe and space (Sophocles, Aeschines, Plautus, Cicero, Virgil and others).” CQ 60(1):96–109.

Irwin, E. 2005. Solon and Early Greek Poetry: the Politics of Exhortation. Cambridge.

Korshak, Y. 1987. Frontal Faces in Attic Vase Painting of the Archaic Period. Chicago.

Lissarrague, F. 1989. “The world of the warrior.” In Bérard 1989:39–52.

———. 1990. The Aesthetics of the Greek Banquet. Princeton.

———. 2008. “Corps et armes: figures grecques du guerrier.” In Dasen and Wilgaux 2008:15–27.

Loraux, N. 1975. “ΗΒΗ et ΑΝΔΡΕΙΑ: deux version de la mort du combattant athénien.” Ancient Society 6:1–31.

Morrison, A. D. 2007. The Narrator in Archaic Greek and Hellenistic Poetry. Cambridge.

Murray, O., ed. 1990. Sympotica: a Symposium on the Symposion. Oxford.

Murray, O. 1991. “War and the Symposium.” In Slater 1991:83–103.

———. 1994. “Nestor’s Cup and the origin of the Greek Symposion.” In D’Agostino and Ridgway 1994:47–54.

Osborne, R. 2007. “Projecting identities in the Greek symposium.” In Sofaer 2007:31–52.

Padgett, J. M. 2003. The Centaur’s Smile. Princeton.

Reitzenstein, R. 1893. Epigramm und Skolion, ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der alexandrinischen Dichtung. Giessen.

Rösler, W. 1990. “Mnemosyne in the Symposion.” In Murray 1990:230–237.

Slater, W.J., ed. 1991. Dining in a Classical Context. Michigan.

Sofaer. J.R., ed. 2007. Material Identities. Malden, MA.

West, M. L. 1993. Greek Lyric Poetry. Oxford.

———. 2011. Hellenica, vol. 1. Oxford.

[1] This paper is a compressed extract from a chapter of my forthcoming monograph on imagery in archaic lyric poetry (OUP). My warmest thanks to all the Fellows and staff of the CHS, and especially to Professors Gregory Nagy, Luca Giuliani, Yiannis Petropoulos, and Dr Madeleine Goh for advice and criticism of various kinds.

[2] Bowie 1986, reviving a view first advanced by Reitzenstein 1893, reviews all contexts of performance previously posited for shorter elegy and convincingly eliminates all but the symposion and the κῶμος; Bowie 1990 positively argues for sympotic performance of Callinus and Tyrtaeus. See, too, Rösler 1990 on the thematic appropriateness of martial exhortation to the sympotic context and Lissarrague 1989 on the martial interest evidenced by sympotic iconography.

[3] Irwin 2005:19–80.

[4] Morrison 2007:94–95. For concentration of abstract and evaluative terms in characters’, rather than the author’s, voice in Homer the classic study is Griffin 1986.

[5] The general terms ‘epic poems’ and ‘Iliadic tradition’ are used in light of the controversy on the relative chronology of the Iliad and martial elegy. Whether or not the Iliad as we know it was in existence in Callinus’ and Tyrtaeus’ day (and this is coming to seem increasingly unlikely), it seems inescapable that martial elegy (which itself must have had a long tradition by the time it rises into view for us fully formed on both sides of the Aegean) was aware of an epic Iliadic tradition of some sort. See especially West 2011:226–232, arguing for several borrowings on the part of the Iliad of the language of Callinus and Tyrtaeus.

[6] Munich Antikensammlungen 2618. On the schema of the ransom of Hector’s body see Giuliani 2013:156–169, with a different though compatible emphasis: his focus is on relating the account of the paintings to that of the Iliad rather than relating the images on the vessels to the sympotic context in which they were meant to be viewed.

[7] On sympotic ‘genre scenes’ as a false category see the Topper 2012:2–4, with references.

[8] Osborne 2007:39.

[9] Translations of Callinus and Tyrtaeus are from West 1989, except for the introduction of ‘stanzaic’ breaks (see below), which are introduced into both Greek and translation following Faraone 2008.

[10] On the extent to which the language of Callinus is Homeric see e.g. Campbell 1967 and Adkins 1977, but see also the salutary cautionary note sounded by Faraone 2008 with references: e.g. elegy seems to lacks many of the particles characteristic of epic and to be unfamiliar with the digamma, and it appears on close inspection to operate by different metrical dynamics. See also Aloni 2009. Close parallels have been noted between our elegy of Callinus and Iliad XV 494–499; XII 95–124; VI 486–493; XII 310–328.

[11] An account of previous scholarship on the implications (sympotic or otherwise) of this verb in Bowie 1990; see also Aloni 2009, who terms this “clear evidence of the sympotic context of this elegy.” To Bowie’s argument (convincing, to my mind) that the symposion is the only possible appropriate situation to such a charge of ‘lying idle’ add the remarks in Murray 1994 on other uses of the term, which is not attested figuratively in Homer or indeed before Xenophon.

[12] Campbell 1967 remarks that is paralleled only by Paulus Silentiarius, a poet of Justinian’s court; he stands corrected by Christenson 2000:631, who notes its pointed use by Achilles Tatius, five times, in an erotic context, in a parodic take on the theme of militia amoris.

[13] There may be a further slight allusion to the sympotic context at line 11: … τὸ πρῶτον μειγνυμένου πολέμου. The expression is not Homeric and Adkins 1977:72–73 remarks that the metaphor may be drawn from the practice of mixing wine “when the dark wine and the clear water are mingled confusedly, not yet fully mixed.”

[14] Faraone 2008.

[15] Faraone 2008:56.

[16] Osborne 2007. Athenian red-figure cup, 525–475 BC; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum 37.19. Images can be viewed freely online on the Beazley Archive website.

[17] Osborne 2007:39.

[18] Korshak 1987.

[19] Frontisi-Ducroux 1991.

[20] Cf. Frontisi-Ducroux 1986.

[21] An account of ancient ideas on apostrophe, especially in relation to the heightening of emotion and with an exploration of the complex effects which can be achieved by it, in Hutchinson 2010.

[22] Loraux 1975.

[23] Cingano 2010.

[24] Athenian red-figure cup, 500–450 BC, signed by Douris. Vienna Kunsthistoriches Museum 3695.

[25] Especially Lissarrague 1990.