Gkotsinas, Angelos. "Animal Diet, Mobility, and Social Complexity in Middle Helladic Central and Northwest Greece." CHS Research Bulletin 13 (2025). https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:106352549.

Early Career Fellow in Hellenic Studies 2024–25

Introduction

The Middle Helladic (MH) period (ca. 2000–1700 BCE) on the Greek mainland has traditionally been portrayed as a “Dark Age,” [1] wedged between the flourishing Early Helladic II and the palatial societies of Late Helladic III. [2] This view stems largely from the relative paucity of monumental architecture and the scarcity of long-distance trade indicators. Some scholars argue that the period was dominated by nomadic and pastoral lifeways that shaped its economy and socio-political organization. [3] Our current understanding, however, derives primarily from cultural material—chiefly pottery—from coastal settlements and islands. In contrast, the inland regions of Central and Northwest Greece—areas with complex ecologies and long-term human occupation—have been largely neglected. As a result, these inland zones remain significantly underexplored in Aegean Bronze Age research, particularly in terms of their economic organization as inferred through the study of biogenic remains, and more specifically, faunal assemblages. [4]

This project, conducted under the auspices of the CHS Early Career Fellowship, aims to reassess the MH period by examining the management of animals—particularly their diet, seasonal patterns, and mobility—as a lens through which to explore broader patterns of social and economic organization. The focus on animal exploitation practices offers a powerful approach to understanding the lived experiences, ecological strategies, and emerging complexities of MH communities.

Study Area and Research Aims

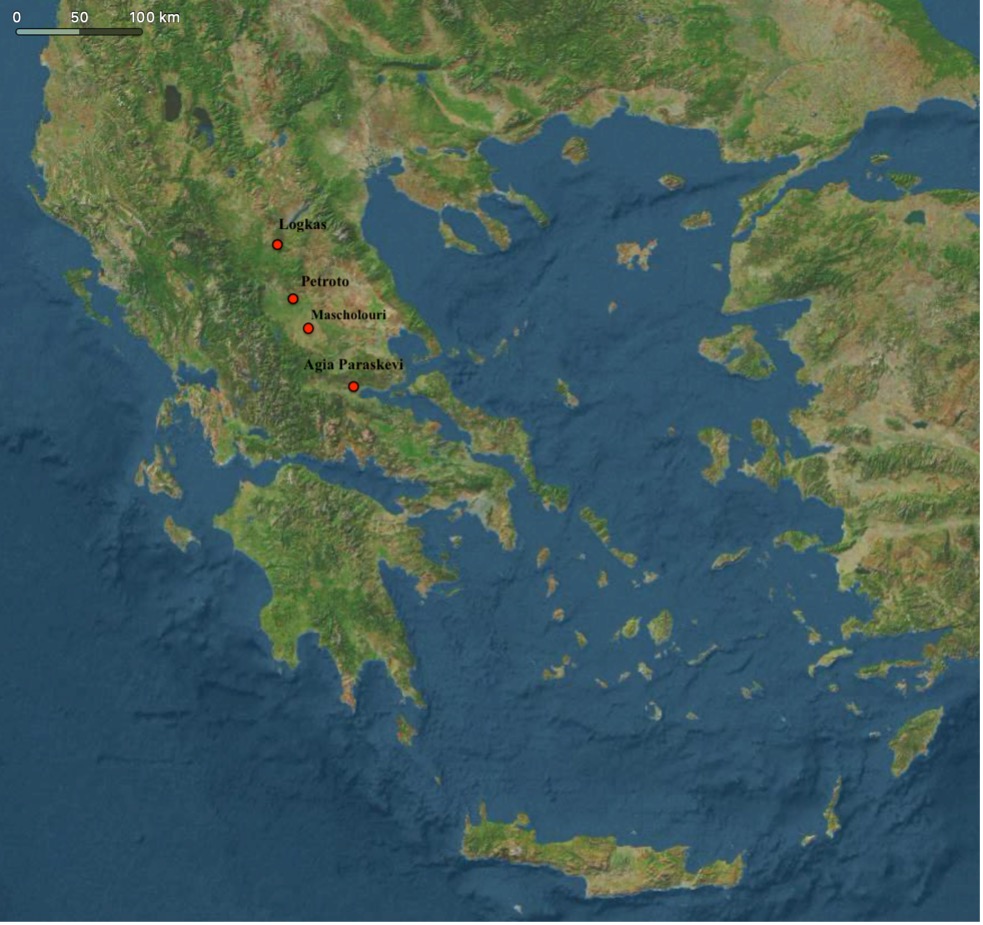

The research draws upon four Middle Helladic sites forming a south-to-north transect across mainland Greece: Agia Paraskevi/Platania in Phthiotis, [5] Mascholouri in Karditsa, [6] Petroto in Trikala, [7] and Logkas in Kozani [8] (Fig. 1) These sites were chosen for their environmental diversity, ranging from deltaic marshes and inland plains to upland valleys, allowing a comparative analysis of subsistence strategies across different ecologies.

The study addresses three interrelated research questions. First, how did environmental and ecological factors influence livestock diets and mobility across these inland settlements? Second, in what ways did the interaction between community location and animal management shape emerging social and economic structures? And third, what role did livestock exploitation play in the transformations that paved the way for the complex societies of the Late Bronze Age?

Methodology

To investigate these questions, the project combines traditional zooarchaeological methods with advanced analytical techniques. Macroscopic analysis of the faunal assemblages includes taxonomic identification, anatomical representation, demographic profiling, biometric measurements, pathological observations, and taphonomic alterations.

These primary observations were then complemented by three high-resolution techniques. Two-dimensional dental microwear analysis was employed to reconstruct short-term dietary signatures in domestic animals by examining chewing-surface abrasion patterns [9] (Fig. 2). Cementochronology enabled the identification of birth and death seasons through incremental analysis of cementum in teeth, shedding light on seasonal herding cycles. [10] Stable isotope analysis—currently underway at the Demokritos research facility in Athens—measured carbon (δ¹³C), nitrogen (δ¹⁵N), oxygen (δ¹⁸O), sulfur (δ³⁴S), and strontium (⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr) values to assess diet, mobility, and geographic origin. [11] The latter technique is being applied to both animal and human remains.

Architecture and Settlement Organization

Archaeological, architectural, and geophysical survey [12] findings from two of the sites under study—namely Platania and Petroto—reveal settlement structures consistent with broader MH architectural patterns. Both sites exhibit unfortified layouts, with houses arranged along alleyways or around open spaces. The predominant architectural form is the apsidal house—elongated with rounded ends—often internally organized into distinct functional zones. Interior features include hearths and storage pits.

Household-level production is attested by the discovery of loom weights and grinding stones, indicating small-scale textile manufacture and food processing. Burial practices further reinforce the household as the central social unit: children at Platania were interred beneath house floors, while adult graves at Petroto were located within the settlement grid. [13] These practices emphasize continuity between the living and the dead and suggest long-term occupation of place.

Animal Exploitation and Subsistence Practices

The analysis of faunal remains from Platania and Petroto reveals distinct species distributions that reflect adaptation to local environments. At Platania, pigs are the most frequently represented species, followed by sheep, cattle, and goats. This pattern corresponds to the limited grazing space available around the settlement, which was further constrained by the presence—according to palaeogeographical studies—of nearby wetlands and a previously extensive coastal lagoon system. [14] This interpretation is further supported by the occurrence of lagoonal mollusks in the archaeological record. [15] Ιn contrast, Petroto is located in the fertile Trikala plain, where cattle dominate the assemblage, followed by sheep, goats, and pigs. The prominence of cattle in this setting reflects a strategic adaptation to intensive agriculture, likely involving an emphasis on traction, as suggested by age-at-death profiles.

Sheep and goats were central to subsistence, though their exploitation strategies varied by site. At Platania, sheep appear to have been primarily managed for fiber production, while goats were raised for meat. At Petroto, both species show a stronger orientation toward secondary products, particularly wool and hair. The scarcity of neonatal remains at both sites suggests that milk production was not a major economic priority. The presence of loom weights at both sites further supports the interpretation of wool-based textile production, likely carried out at the household level.

Cattle were typically maintained into adulthood, and pathological changes observed on phalanges from Petroto are consistent with stress injuries associated with draft work. This provides strong evidence for the use of cattle in ploughing and other traction-related activities, a practice well-suited to Petroto’s broad alluvial landscape. Pigs, by contrast, were generally slaughtered before their first year of life, indicating a focus on rapid meat production. Some subadult individuals may have been kept longer for fattening purposes, particularly at Platania.

Animal processing appears to have taken place within the settlements. Skinning marks are concentrated on skulls and lower limbs, while dismemberment cuts occur at major joints. Filleting marks along the diaphyses of long bones and evidence of marrow extraction from large cattle bones suggest systematic meat harvesting and consumption. Culinary practices inferred from bone surface modifications indicate that boiling was the predominant cooking method. The scarcity of burned bones implies that roasting was infrequent—possibly reserved for special occasions or communal feasts—while boiling likely constituted the everyday norm.

Wild animals were present at both sites, albeit in modest quantities. At Platania, the faunal assemblage also includes marine species, consistent with the site’s Bronze Age proximity to a coastal or lagoonal environment. Red deer dominate the game spectrum, followed by wild boar and fallow deer—the latter found only at Platania. Butchery marks on these remains suggest they were primarily exploited for meat, though antler and boar tusks may have been used for crafting purposes.

A particularly noteworthy find is a boar’s tusk plate from Platania, almost certainly part of a boar’s tusk helmet. Such helmets are typically associated with Mycenaean elites of the Late Helladic period, but the example from Platania dates to MH II and constitutes one of the earliest known instances of this prestigious artifact type. Its presence at a non-palatial site highlights the emergence of social differentiation well before the Mycenaean palaces, suggesting that mechanisms of elite display were already taking shape during the Middle Bronze Age.

Dogs were also part of the domestic and settlement landscape. Remains from both sites show evidence of gnawing, suggesting their role as scavengers. Their association with other domestic species further indicates that dogs may have been used as guards, hunters, or even companions. Alongside canids, the presence of equids also deserves mention. Although a single equid bone from Petroto may belong to a later phase—when equids are securely attested both archaeologically and in written sources such as Linear B tablets—the evidence from Middle Helladic Logkas, where equid burials have been found, suggests that these animals were likely known and perhaps already employed for transport or riding during the MH period. [16]

Beyond species presence and exploitation, the treatment of animal remains within settlements offers further insights into daily life and social practices. Taphonomic observations from both sites reveal mixed strategies of bone disposal. Some assemblages contain articulated remains that were likely buried shortly after discard, suggesting controlled waste management. Other bones exhibit signs of gnawing, weathering, and trampling, indicating longer surface exposure. This variation reflects differences in household discard practices and suggests that certain contexts—perhaps tied to communal or ceremonial activities—produced refuse managed separately from everyday domestic waste.

Conclusion

The research conducted through the CHS Early Career Fellowship presents the first multi-site, high-resolution investigation of animal economies in Middle Helladic inland Greece. Preliminary findings reveal communities that were both stable and adaptive—managing herds with sophistication, exploiting diverse environments, and engaging in symbolic practices that anticipate later Mycenaean traditions. Variability in species exploitation, cattle traction, and butchery techniques suggests regional economic differentiation, while the presence of elite artifacts, such as the boar’s tusk plate, points to the emergence of social hierarchies.

The ongoing laboratory work—which integrates zooarchaeological, dental microwear, cementochronological, and isotopic data—continues to deepen our understanding of animal management strategies, dietary practices, and seasonal rhythms across ecologically distinct landscapes, contributing to a more nuanced reconstruction of Middle Helladic society. By placing animal management at the center of Bronze Age lifeways, the project offers new perspectives on the socio-environmental foundations of Aegean complexity.

This research would not have been possible without the financial support of the CHS Early Career Fellowship and access to Harvard’s library resources. The opportunity to work at the CHS facilities in Washington, D.C., and Nafplio has further enriched the experience—both academically and personally.

References

Ambrose, S. H., and L. Norr. 1993. “Experimental evidence for the relationship of the carbon isotope ratios of whole diet and dietary protein to those of bone collagen and carbonate.” In Prehistoric human bone: Archaeology at the Molecular Level, eds. J. B. Lambert and G. Grupe, 1–37. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-02894-0_1.

Bennet, J. 2013. “Bronze Age Greece.” In The Oxford Handbook of the State in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean, eds. P. F. Bang and W. Scheidel, 235–258.Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

DeNiro, M. J., and S. Epstein. 1978. “Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals.” Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 42(5):495–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(78)90199-0.

Dickinson, O. T. P. K. 1977. The Origins of Mycenaean Civilisation. SIMA Vol. 49. Göteborg: Paul Åströms Förlag.

Dickinson, O. T. P. K. 1989. “‘The Origins of Mycenaean Civilisation’ revisited.” In Transition: Le monde égéen du Bronze moyen au Bronze récent, ed. R. Laffineur, 131–136. Aegaeum 3. Liège: Université de Liège.

Dickinson, O. T. P. K. 2010. “The ‘Third World’ of the Aegean? Middle Helladic Greece revisited.” In Mesohelladika: La Grèce continentale au Bronze Moyen, eds. A. Philippa-Touchais, G. Touchais, S. Voutsaki, and J.C. Wright, 13–27. Athens: École française d’Athènes.

Gkotsinas, A. 2018. “Animal burials in the Early and Middle Helladic cemetery of Logkas Elatis. Presentation of the burials and preliminary results of the zooarchaeological study” [Ενταφιασμοί ζώων στο νεκροταφείο της Πρώιμης και Μέσης Εποχής του Χαλκού στην Ελάτη, θέση Λογκάς. Παρουσίαση ταφών και προκαταρκτικών αποτελεσμάτων ζωοαρχαιολογικής μελέτης]. In The Archaeological Work of Upper Macedonia, 3 (2013), ed. G. Karamitrou-Mentessidi, 65–79. Aiani.

Gkotsinas, A., A. Karathanou, M. F. Papakonstantinou, G. Syrides, and K. Vouvalidis. 2014. “Approaching human activity and interaction with the natural environment through the archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological remains from Middle Helladic Agia Paraskevi.” In Physis: L’environnement naturel et la relation homme-milieu dans le monde égéen protohistorique, eds. G. Touchais, R. Laffineur, and F. Rougemont, 487–494. Aegaeum 37. Leuven–Liège: Peeters.

Hielte, M., 2004. “Sedentary versus nomadic life-styles: the ‘Middle Helladic People’ in southern Balkan (late 3rd & first half of the 2nd Millennium BC).” Acta Archaeologica 75(2): 27–94.

Hourmouziadis, G. Ch. 1979. “Agia Paraskevi (Platania)” [Αγία Παρασκευή (Πλατάνια)]. Archaiologiko Deltion (ΑΔ) 29:518–519.

Karamitrou-Mentessidi, G., 2006. “Kozani and Grevena Prefectures: Public Electricity Corporation S.A. (Ilarion Dam) and Antiquities” [Νομοί Κοζάνης και Γρεβενών: ΔΕΗ Α.Ε. (Φράγμα Ιλαρίωνα) και Αρχαιότητες].” In The Archaeological Work in Macedonia and Thrace, eds. P. Adam-Veleni and K. Tzanavari, 609–622. (ΑΕΜΘ) 18. Thessaloniki.

Karamitrou-Mentessidi, G. 2008. “The Ilarion Dam 2006: Research in the Elati, Panayia and Paliouria areas” [Φράγμα Ιλαρίωνος 2006: Έρευνα στην Ελάτη, Παναγιά και Παλιουριά].” In The Archaeological Work in Macedonia and Thrace (ΑΕΜΘ), eds. P. Adam-Veleni and K. Tzanavari, 20:875–894. Thessaloniki.

Karamitrou-Mentessidi, G. 2014. “The work of the 30th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities during 2010” [Από το ανασκαφικό έργο της Λ΄ Εφορείας Προϊστορικών και Κλασικών Αρχαιοτήτων κατά το 2010]. In The Archaeological Work in Macedonia and Thrace (ΑΕΜΘ), eds. P. Adam-Veleni and K. Tzanavari, 24:17–38 Thessaloniki.

Karamitrou-Mentessidi, G. 2015. “From the excavation work of the 30th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities during 2011” [Από το ανασκαφικό έργο της Λ΄ Εφορείας Προϊστορικών και Κλασικών Αρχαιοτήτων κατά το 2011].” In The Archaeological Work of Macedonia and Thrace (ΑΕΜΘ), 25:37–61. Thessaloniki.

Karamitrou-Mentessidi, G. 2017. “Research on Mavropigi and the Ilarion dam during 2012” [Η έρευνα στη Μαυροπηγή και στο φράγμα Ιλαρίωνα κατά το 2012]. In The Archaeological Work in Macedonia and Thrace (ΑΕΜΘ), eds. P. Adam-Veleni and K. Tzanavari, 26:47–90. Thessaloniki.

Karamitrou-Mentessidi, G., and D. Theodorou. 2013. “Research in Ilarion dam (Haliakmon): Excavation in Logka Elatis” [Από την έρευνα στο φράγμα Ιλαρίωνα (Αλιάκμων): η ανασκαφή στον Λογκά Ελάτης]. In The Archaeological Work in Macedonia and Thrace (ΑΕΜΘ), eds. P. Adam-Veleni and K. Tzanavari, 23:53–62. Thessaloniki.

Naji, S., L. Gourichon, and W. Rendu. 2015. “La cémentochronologie.” In Messages d’Os: Archéométrie du squelette animal et humain, eds. M. Balasse, J.-P. Brugal, Y. Dauphin, E.-M. Geigl, C. Oberlin, and I. Reiche, 217–240. Paris: Éditions des Archives contemporaines.

Papakonstantinou, M.-F., and T. Krapf. 2020. “Middle Helladic settlement at Agia Paraskevi, Lamia Excavations 2012-2013” [Μεσοελλαδικός οικισμός Αγίας Παρασκευής Λαμίας. Ανασκαφικές έρευνες 2012–2013]. In The Archaeological Work in Thessaly and Central Greece (ΑΕΘΣΕ), ed. A. Mazarakis Ainian, 5(I):863–876. Volos.

Papakonstantinou, M.-F., and T. Krapf. 2022. “The Middle Helladic settlement of Agia Paraskevi at Lamia: New excavation results” [Ο Μεσοελλαδικός Οικισμός Αγίας Παρασκευής Λαμίας: Νεότερα Ανασκαφικά Δεδομένα]. In The Archaeological Meeting of Thessaly and Central Greece (ΑΕΘΣΕ), ed. A. Mazarakis Ainian, 5(II):821–834. Athens.

Papakonstantinou, M.-F. and K. Vouvalidis. 2015. “Archaeological and palaeogeographical research in the Spercheios valley (APEKS): First presentation” [Αρχαιολογική και Παλαιογεωγραφική Έρευνα στην κοιλάδα του Σπερχειού (ΑΠΕΚΣ). Πρώτη παρουσίαση]. In Proceedings of the 5th Conference on the History of Phthiotis, 16–18 April 2010, 23–38. Lamia.

Papakonstantinou, M. F., T. Krapf, N. Koutsokera, A. Gkotsinas, A. Karathanou, K. Vouvalidis, and G. Syrides. 2015. “Agia Paraskevi, Lamia: The cultural and natural environment of a settlement in the deltaic plain of the Spercheios River during the Middle Helladic period” [Αγία Παρασκευή Λαμίας, θέση «Πλατάνια». Το πολιτισμικό και φυσικό περιβάλλον ενός οικισμού στη δελταϊκή πεδιάδα του Σπερχειού κατά τη Μέση Εποχή του Χαλκού]. In The Archaeological Work in Thessaly and Central Greece (ΑΕΘΣΕ), ed. A. Mazarakis Ainian, 4(II):989–998. Volos.

Rivals, F., 2015. “L’analyse de la micro- et meso-usure dentaire: méthodes et applications en archéozoologie.” In Messages d’Os. Archéométrie du squelette animal et humain, eds. M. Balasse et al., 241–254. Paris: Éditions des Archives contemporaines. https://doi.org/10.17184/eac.3999.

Syrides, G., E. Aidona, K. Vouvalidis, M.-F. Papakonstantinou, S. Pehlivanidou, and N. Koutsokera. 2015. “Anthropogenic and natural sedimentary records from the prehistoric settlement of Agia Paraskevi, Lamia” [Ιζηματογενείς καταγραφές ανθρωπογενών και φυσικών διεργασιών στον προϊστορικό οικισμό της Αγίας Παρασκευής Λαμίας]. In The Archaeological Work in Thessaly and Central Greece (ΑΕΘΣΕ), ed. A. Mazarakis Ainian, 4(II):893–899.Volos.

Tsokas, G. N., A. Stampolidis, G. Vargemezis, P. Tsourlos, M.-F. Papakonstantinou, and N. Koutsokera. 2015. “Geophysical investigation and exavation of limited scale at the site “Plataniα” Agias Paraskevis in the Municipality of Lamia” [Γεωφυσική διασκόπηση και συνακόλουθη σύντομη ανασκαφική έρευνα στη θέση «Πλατάνια» Αγίας Παρασκευής Λαμίας]. In The Archaeological Work in Thessaly and Central Greece (ΑΕΘΣΕ), ed. A. Mazarakis Ainian, 4(II):911–918. Volos.

Vaiopoulou, M. 2015a. “‘Raches’ Mascholouri: A settlement at the transitional from MBA III to LBA. A first presentation” [«Ράχες» Μασχολουρίου: Οικισμός της μεταβατικής περιόδου από τη Μέση Εποχή Χαλκού ΙΙΙ στην Ύστερη Εποχή Χαλκού. Μια πρώτη παρουσίαση]. In The Archaeological Work in Thessaly and Central Greece (ΑΕΘΣΕ), ed. A. Mazarakis Ainian, 4(I):177–186. Volos.

Vaiopoulou, M. 2015b. “A new settlement of the Middle and Late Bronze Age in location ‘Asvestaria’ of Petroto, Trikala” [Οικισμός της Μέσης και Ύστερης Εποχής Χαλκού στη θέση «Ασβεσταριά» του Πετρωτού Τρικάλων]. Trikalina 35:205–220. Proceedings of the 10th Symposium of Trikala Studies. Trikala.

Vaiopoulou, M. 2019. “A settlement at the place «Asvestaria» in Petroto, Trikala. A prehistoric settlement with timeless residence from LN to LHIIIC” [Οικισμός στη θέση «Ασβεσταριά» Πετρωτού Τρικάλων (Δυτική Θεσσαλία): Ένας προϊστορικός οικισμός με διαχρονική κατοίκηση από τη ΝΝ έως την ΥΕ ΙΙΙΓ]. Themes in Archaeology (Θέματα Αρχαιολογίας) 3(3):320–337.

Vaiopoulou, M. 2022. “Five years of excavations at the Bronze Age settlement of “Asvestaria” Petrotou, near Trikala” [Πέντε χρόνια ανασκαφικών ερευνών στον οικισμό της Εποχής Χαλκού στη θέση «Ασβεσταριά» Πετρωτού, Τρικάλων]. In: The Archaeological Work in Thessaly and Central Greece (ΑΕΘΣΕ), ed. A. Mazarakis Ainian, 6(I):247–255. Athens.

Van der Merwe, N. J., and J. C. Vogel. 1978. “13C content of human collagen as a measure of prehistoric diet in woodland North America.” Nature 276(5690):815–816. https://doi.org/10.1038/276815a0.

Vouvalidis, K., G. Syrides, K. Pavlopoulos, M. Papakonstantinou, and P. Tsourlos. 2010. “Holocene palaeoenvironmental changes in Agia Paraskevi prehistoric settlement, Lamia, Central Greece.” Quaternary International 215:64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2009.08.016.

Wiersma, C. 2014. Building the Bronze Age: Architectural and social change on the Greek Mainland during Early Helladic III, Middle Helladic and Late Helladic I. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Wiersma, C., and S. Voutsaki, eds. 2017. Social Change in Aegean Prehistory. Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow Books.

Zafeiri, D., S. Triantafyllou, and M. Vaiopoulou. 2022. “Skeletal remains analysis from Petroto, Trikala” [Μελέτη σκελετικών καταλοίπων από το Πετρωτό του νομού Τρικάλων]. In The Archaeological Work in Thessaly and Central Greece (ΑΕΘΣΕ), ed. A. Mazarakis Ainian, 6(I):257–267. Athens.

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. Dickinson 1977; 1989; 2010.

[ back ] 2. Bennet 2013.

[ back ] 3. Hielte 2004.

[ back ] 4. Wiersma 2014; Wiersma & Voutsaki 2017.

[ back ] 5. Hourmouziadis 1979; Papakonstantinou & Krapf 2020; 2022; Papakonstantinou et al. 2015.

[ back ] 6. Vaiopoulou 2015a.

[ back ] 7. Vaiopoulou 2015b; 2019; 2022.

[ back ] 8. Karamitrou-Mentessidi 2006; 2008; 2014; 2015; 2017, Karamitrou-Mentessidi & Theodorou 2013.

[ back ] 9. Rivals 2015.

[ back ] 10. Naji et al. 2015.

[ back ] 11. Ambrose & Norr 1993; DeNiro & Epstein 1978; van der Merwe & Vogel 1978.

[ back ] 12. For Platania: Tsokas et al. 2015.

[ back ] 13. Zafeiri et al. 2022.

[ back ] 14. Papakonstantinou & Vouvalidis 2015; Vouvalidis et al. 2010.

[ back ] 15. Gkotsinas et al. 2014; Syrides et al. 2015.

[ back ] 16. Gkotsinas 2018.