Christakopoulou, Olga. "Cracking the Code: Symbols, meanings and networks in Early Iron Age Greece; Evidence from the Stamna pottery. The qualitative approach." CHS Research Bulletin 12 (2024). https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:105019626.

I. Stamna Basics

The Protogeometric period in Stamna, Aetolia, initially came to light through isolated rescue excavations conducted intermittently over the past thirty years. [1] However, it gained recognition as an extensive cemetery of this period following a rescue excavation conducted from 1998 to 2000, prompted by the construction of a bypass highway.

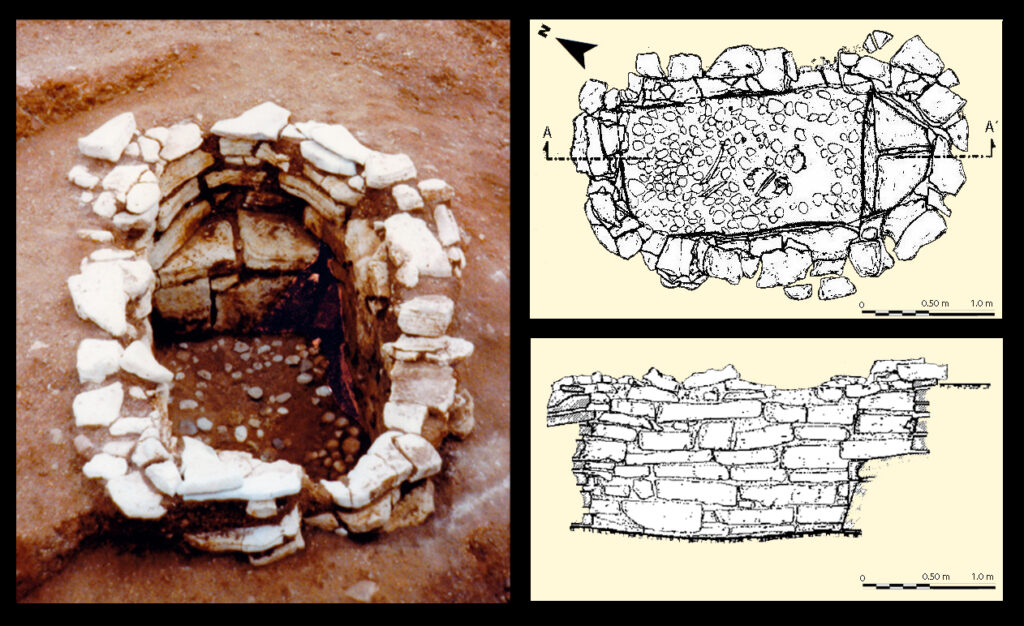

The region of Aetolia (FIG.1) remains a complex landscape that has historically attracted ancient settlers over the centuries. My 1994 excavation of a monumental apsidal tomb in Stamna, Aetolia (FIG.2), unique in both Greek and international literature for its typology, the nature of the burials it hosted, and their grave goods—stimulated my desire to explore and subsequently study the ancient cemetery in this area.

The study of the cemetery in Stamna, predominantly dating to the Protogeometric period and displaying distinct Mycenaean influences, has opened new avenues for historical research within a region previously marginalized as the outskirts of the Greek world. Stamna has now secured its place on the archaeological map of the Protogeometric period in Greece. Its necropolis, yet to be fully excavated, unveils a notable human presence during an era previously understudied, underscored by the remarkably intact condition of its tombs.

Spanning dozens of hectares along and around the lagoon of Aetoliko (FIG.3), an area of unparalleled natural beauty even today, the findings suggest a population that settled intentionally, aware of the advantages of this specific location. Over the years, due to rescue excavations for housing construction and the development of the bypass highway, the excavation site in Stamna has served as an open-air museum, providing a space for “reading” the archaeological landscape.

[But what lies behind the name “Stamna”?

The story begins in the Middle Neolithic period (5800 to 5300 BC), where Stamna emerged as a vessel crafted for the transportation and storage of liquids. The Stamna vessel served various purposes on different occasions, from dispensing water to pouring wine or oil. The term “Stamna” finds its roots in the Byzantine era, derived from “stamnion,” which traces back to the ancient Greek verb ἵστημι signifying its ability to stand independently. The abundance of ancient clay vessels discovered in the area suggests the presence of local workshops, giving credence to Stamna’s evolution into a hub for pottery production in later years. This archaeological evidence not only enriches our understanding of the region’s past but also justifies the enduring legacy of the name “Stamna” in describing its pottery tradition].

II. Stamna Non-Basics

Throughout history, art has served as a universal medium through which individuals and societies process loss. Whether experiencing the loss of a loved one or confronting catastrophic events like a devastating pandemic, people are compelled to reassess the value of life with greater intensity. The sobering realization that death is irreversible fosters a profound need for communication among the living. This urge to bridge the void left by death compels individuals to articulate unexpressed emotions and bestow posthumous honors upon the departed.

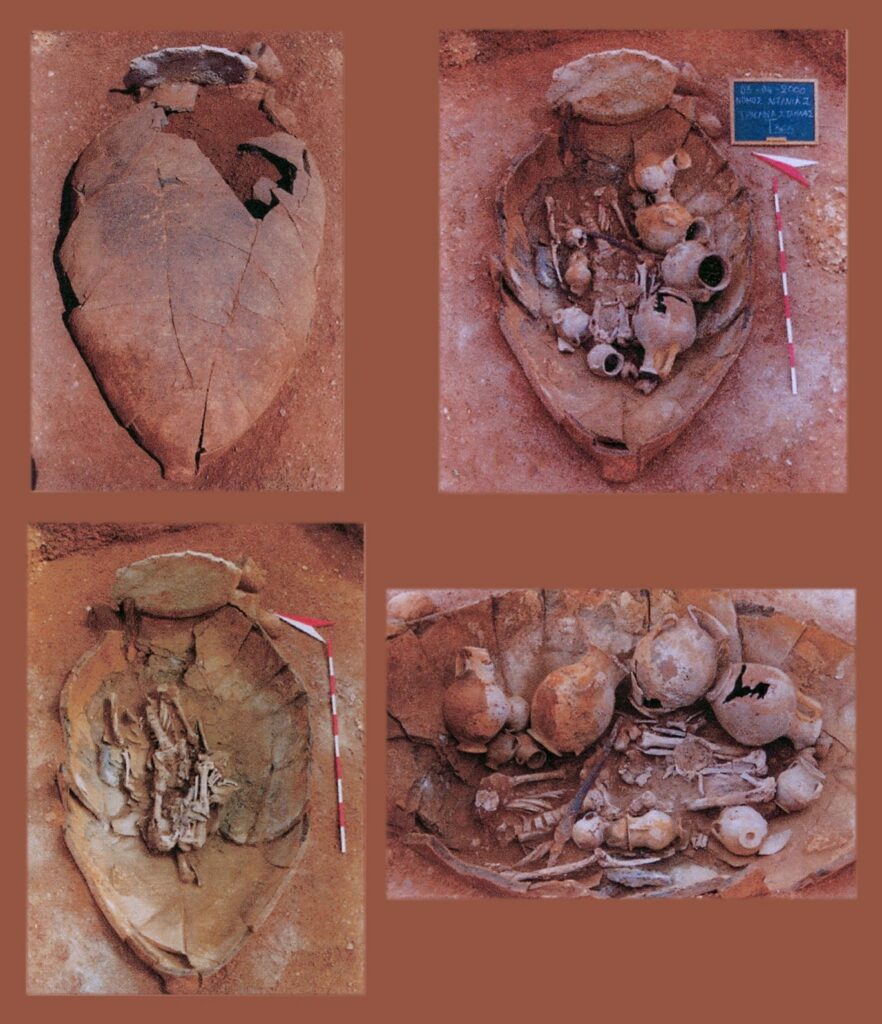

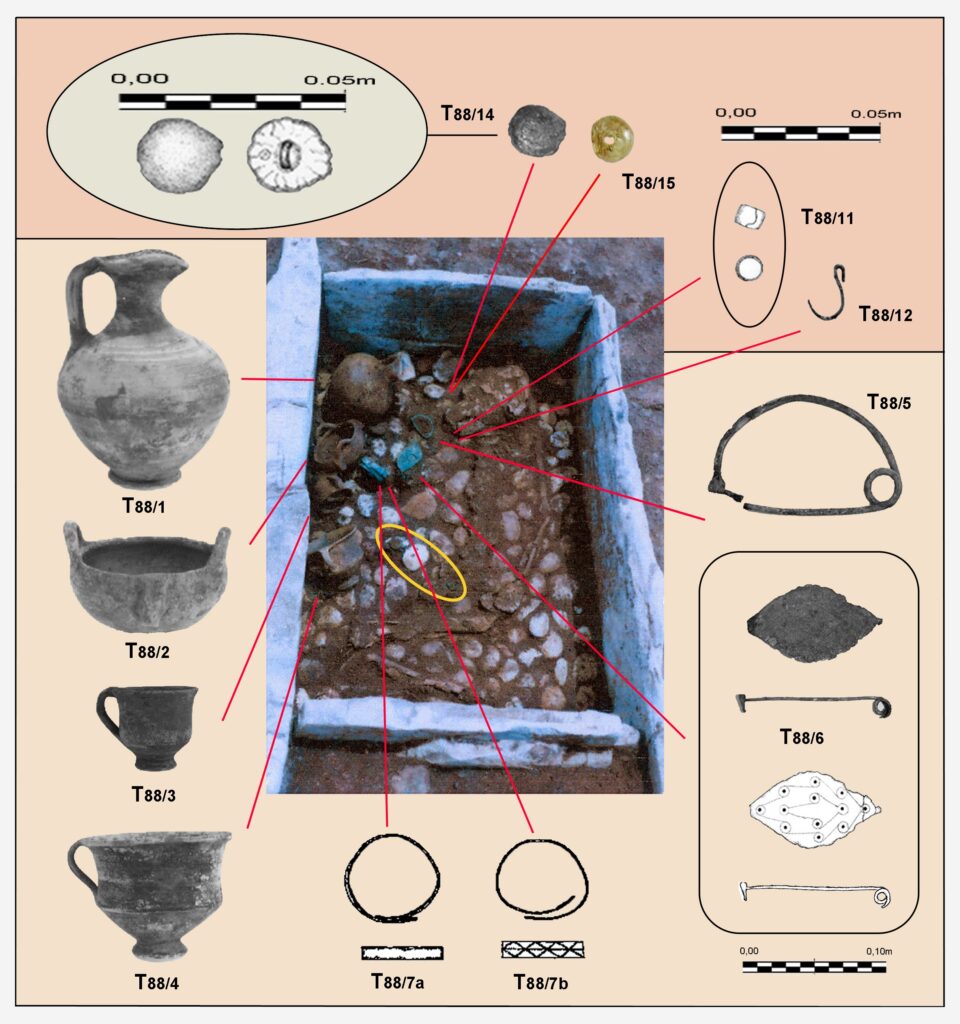

Grave offerings (FIG. 4 and 5) and the items included as grave goods serve as essential means of personal communication, allowing the deceased to be honored and remembered by their loved ones. The widespread presence of symposium vessels in Stamna suggests that the population highly valued ritual feasting as a key aspect of their worship practices. These vessels, found in the graves, not only symbolize communal dining but may also carry personal significance through their decorative elements, reflecting the individual connections and sentiments of those who placed them there.

Initially, we assume that the typological development of pottery follows a progression, akin to a gradient on an imagined statistical chart. In this chart, vessel types and motifs evolve in form and design over time, influenced by accumulated experience. Concerning Stamna, we currently lack significant numerical datasets that could delineate a continuous evolution within the Protogeometric period (early, middle, late). This lack of data hinders our ability to clearly identify shifts in the socio-political structure of the settlement and cemetery. Most ceramic findings date to the late Protogeometric period, with only a few examples from the early and middle phases.

This project attempts a first approach of the cultural significance of the individual and recurring motifs/symbols that adorned ceramic vessels at Stamna Aetolia (FIG. 6), yielded from the excavation of 500 tombs. Their evaluation is based on the motifs’ geometry, their spatial arrangement on the respective surface, and also on aesthetic criteria. We believe that they have functioned as symbols of identity, encrypting social notions which extend across or beyond ethnic identities in the wider region of Eastern Mediterranean, the Aegean, Asia Minor etc. The title “Cracking the Code” signifies our willing to decode the meanings hidden behind the deposition of these archaeological findings. Through this project, we aim to unearth the concealed messages and cultural connections that shape the puzzle of the past. Additionally, the title also symbolizes the effort to bridge relationships between different cultures, highlighting their common roots and influences, deepening our comprehension of global cultural interactions.

This project constitutes a collaborative project. The interpretation of the motifs will be supported by Quantitative analysis that employs GIS techniques.

III. Symbols and meanings (The Art of Knowing)

Ceramic typology stands as one of humanity’s oldest forms of design, where decoration and symbolism play vital roles in enhancing its significance. Much like in the field of design, potters strive to achieve an ideal balance between functionality and aesthetics. Equally meticulous, vase painters employ symbolism that underscores the intricacies of human development and the enduring cultural legacy of their respective communities.

During the Late Iron Age, potters in Stamna created utilitarian vessels and cooking utensils primarily to meet their daily needs, evident from tomb findings which indicate these vessels accompanied them into the afterlife. Their vessels take shapes that appear to correspond to daily living conditions, primarily associated with drinking vessels, followed by food, serving, storage, and transport utensils. Thus, it is no coincidence that vessels catering to these needs are numerically dominant in Stamna, particularly amphorae (268) and oinochoae (159), imbuing them with a dual character: everyday utility and ceremonial significance (symposium).

Maintaining consistent typological forms throughout the cemetery’s use, along with employing similar linear patterns at specific locations on their surfaces (FIG. 6), reflects enduring living conditions over the settlement’s extensive history. This continuity underscores the potential of ancient techniques to reveal new pathways in symbolism and evaluation, encouraging us to move beyond rigid categorization of forms and standardized recording of linear motifs towards innovative interpretations.

Beyond the domains of art and archaeology, let us briefly consider the individuals who crafted these artifacts—their values and experiences. What dreams did they cherish? What untold stories are concealed within these artworks? Vase painters should be recognized as skilled artisans who not only captured shapes and colors but also infused their creations with the dynamic, enigmatic spirit that characterized ancient artists—the human creators. This perspective aims to illustrate that these vase painters were not merely skilled craftsmen but also expressed a profound, nuanced spiritual essence in their works, reflecting the creativity and complexity of ancient artists.

Thus, we understand that the vessels used by the inhabitants of Stamna to accompany their dead, adorned with specific motifs, represented something more than mere ceramic objects. Each motif, color, and design chosen by the deceased’s relatives expressed and reflected the life and personality of the deceased posthumously. This conclusion underscores the deeper cultural and personal significance of the artifacts found in Stamna.

IV. Cracking the Code: Theoretical Framework and Methodology (Knowledge is Bliss)

IV.1 Theoretical Framework

This study represents an initial exploration into the cultural significance of individual and recurring geometric patterns/symbols adorning ceramic vessels from Stamna, Aetolia. The evaluation of these motifs is grounded in geometric principles, aesthetic criteria, and their spatial structure on each surface. The theoretical framework for this research is based on the following assumptions to trace the population’s origin through the patterns on their burial vessels:

1.1 Continuity in Tradition:

A stable tradition of using specific geometric motifs on burial vessels during the specified period implies that a consistent practice was followed over a sufficiently long duration to establish a coherent tradition. This assumption is rooted in the theoretical understanding of cultural transmission and tradition maintenance within anthropological and archaeological contexts.

1.2 Transmission of Traditions:

The population maintained the tradition of using specific geometric motifs even when relocating. This theoretical perspective aligns with the concept of cultural transmission, where traditional knowledge and practices are passed down through generations, ensuring continuity despite geographical relocations.

1.3 Cultural Identity:

The population’s origin must be closely tied to a unified cultural identity that preserves consistent geometric motifs and burial practices across different regions. This assumption is based on theories of cultural identity, which emphasize the role of shared symbols and practices in maintaining group cohesion and identity.

IV.2 Methodology

To address the research questions posed in this project, we constructed comprehensive databases and derived preliminary conclusions (Simoni 2024). The methodology involved several key steps:

2.1 Database Creation:

Greek Data: This database includes geometric patterns and locations from across Greece, encompassing various regions and time periods.

International Data: This database covers sites and geometric motifs in the Eastern Mediterranean, including Cyprus and Italy, as well as regions in Asia. Additionally, data were gathered from visits to museums such as the Smithsonian Museums (Washington D.C.), The Walters Art Museum (Baltimore), and the MET (New York), focusing on sites and populations in the Americas.

2.2 Data Analysis:

Pattern Frequency and Distribution: We analyzed the frequency of specific geometric motifs at various sites to identify potential connections. This analysis was based on particular parameters, primarily chronological, to understand the temporal context of these populations.

Assumptions and Typology of Burials:

- Development of Site-Specific Databases: We documented distinguished burials, categorizing them based on tomb typology and associated grave goods.

- Characteristics of Distinguished Burials: Common characteristics of elite burials were identified to facilitate their recognition in other regions.

2.3 Pattern Analysis Example:

Search for Specific Patterns: We examined whether certain geometric motifs, such as triangles or zigzags, were exclusively found in distinguished burials. This step involved detailed pattern recognition analysis and comparative studies across different sites.

2.4 Categorization Process:

Data Compilation: Created tables documenting data from distinguished burials, analyzing their characteristics.

Regional Comparison: Used this data to categorize similar groups of burials in other regions, such as Stamna, based on vessel decoration and geometric motifs.

2.5 Further Analysis:

Motif Count per Vessel: Recorded the number of geometric motifs on each vessel, as this provides significant information about the complexity and variation of the decorative patterns.

By integrating the data on geometric motifs with the broader archaeological context, including tomb typology and associated grave goods (Simoni 2024), we can draw more nuanced conclusions about the cultural significance of these patterns. The preliminary findings suggest that certain geometric motifs were consistently used across different regions, highlighting a shared cultural identity and practices among these ancient populations. This theoretical approach underscores the importance of geometric motifs in understanding the archaeological record and the cultural continuity, identity, and transmission among ancient societies.

V. Preliminary Conclusions (Too Dark in Here?)

This study aimed to elucidate how decorative motifs on pottery functioned as cultural markers and indicators of elite status, not only within the prosperous settlement of Stamna but also across various regions in Greece and internationally during the same period. By leveraging advanced technological methods, our research has yielded significant findings, guiding us into specialized areas concerning the migration and settlement of populations. These insights extend beyond the studied period to other historical eras, as evidenced by the consistent motifs found in pottery. This broader perspective underscores the importance of geometric patterns as indicators of cultural transmission and population movements, providing deeper insights into ancient societies and their interconnectedness.

Traditionally, pottery evaluations have relied on descriptive accounts of decorative motifs. This study aims to provide precise and quantitative analysis of the material evidence associated with these motifs, treating them as case studies both preceding the emergence of Iron Age populations and prior to the collapse of Mycenaean palatial centers. Our research offers quantitative documentation of decorative motifs not only in Stamna but also beyond the conventional boundaries of the Greek world, employing an ethnoarchaeological and diachronic approach. This investigation raises questions about trade during this period—whether the presence of specific motifs indicates trade routes, imports, exports, or merely local phenomena in ceramic decoration. The abundance of tombs, their architectural originality, and their clustered arrangements, along with associated grave goods and forms of worship, reflect a dynamic organization of settlements both spatially and functionally, independent of gender. During our fellowship, distinct case studies were conducted on the dispersion of specific motifs, not only within the Stamna cemetery but also across the broader Greek and international contexts during the Early Iron Age and preceding and following it.

Focusing on cultural exchange, typology of tombs, burial practices, vessel typology, and decorative motifs—all documented using methods employed by colleague and GIS systems specialist, Helene Simoni, it became evident that Stamna had close relationships and influences from other regions (Simoni 2024). These relationships facilitated the exchange of products and ideas with other ancient communities, promoting the international dissemination of cultural elements despite Stamna’s initial apparent isolation. More specifically, the procedures followed and the objectives pursued are summarized as follows:

V.1 Symbols, meanings and networks: Findings and Interpretation

Advanced Technological Methods: The use of advanced technological methods, such as GIS mapping and detailed pattern analysis, led to significant findings. These techniques provided deeper insights into population movements and settlement patterns.

Cultural Markers and Elite Status: Decorative motifs on pottery served as significant cultural markers and indicators of elite status. These motifs were not merely decorative but symbolic, aiding in the identification and distinction of elite groups within Stamna and beyond, across Greece and internationally.

Quantitative Analysis of Motifs: Unlike traditional descriptive methods, this study offers precise quantitative analysis of decorative motifs. This approach provides concrete evidence of the significance and usage of these motifs, tracing their presence from before the Iron Age to the collapse of Mycenaean palatial centers.

Temporal and Geographical Scope: The insights gained extend beyond the studied period to other historical eras, as indicated by the consistent presence of pottery motifs. The recurring patterns across different time periods suggest long-term cultural transmission and influence across various regions.

Trade and Cultural Exchange: The presence of specific motifs raises questions about trade routes and cultural exchange networks. These motifs likely indicate extensive trade interactions and cultural exchanges, suggesting they were part of a broader system of cultural exchange rather than isolated local phenomena in ceramic decoration.

Organization of Tombs and Grave Goods: The unique architectural styles and clustered arrangements of tombs, along with diverse grave goods, reflect a well-organized settlement structure. These characteristics point to a complex society with distinct spatial and functional organization, unaffected by gender roles, highlighting social complexity.

Case Studies on Motif Dispersion: Case studies revealed the dispersion of specific motifs across Stamna and beyond during and after the Protogeometric period. These studies illustrate how certain motifs spread spatially and temporally, shedding light on patterns of cultural diffusion and interaction.

Cultural Influences and Relationships: Stamna exhibited close relationships and influences from other regions, as demonstrated by GIS specialist Helene Simoni. These connections facilitated the exchange of goods and ideas with other ancient communities, promoting the international dissemination of cultural elements despite initial perceptions of Stamna’s isolation.

V.2 From Research to Publication: The ‘Cracking the Code’ Journey

It should be noted that the results of our collaboration with Helene Simoni are part of a larger endeavor. The overall aim of the project is to publish a corpus in a monograph titled, The ‘Cracking the Code’ Project: Pattern is the Key, a significant portion of which has already been written during our fellowship at the CHS.

VI. Exploring Research sub-projects: Insights from the CHS Fellowship

VI.1 Collaborative articles/presentations

Thanks to the Harvard fellowship, Helene Simoni and I have successfully completed three sub-projects under the umbrella of the main project. The first of these sub-projects is set to be published by Archaeopress Publishing House in Oxford.

1st sub-project | Christakopoulou, G., and H. Simoni, “The ‘Cracking the Code‘ project; Stamna’s Pithoi Workshops: Unveiling Pottery Heritage,” in Workshops / Ateliers / Werkstaetten: Premises and Processes of Creation in Antiquity, eds. C. E. Partida and C. Graml. Oxford, Archaeopress (in press).

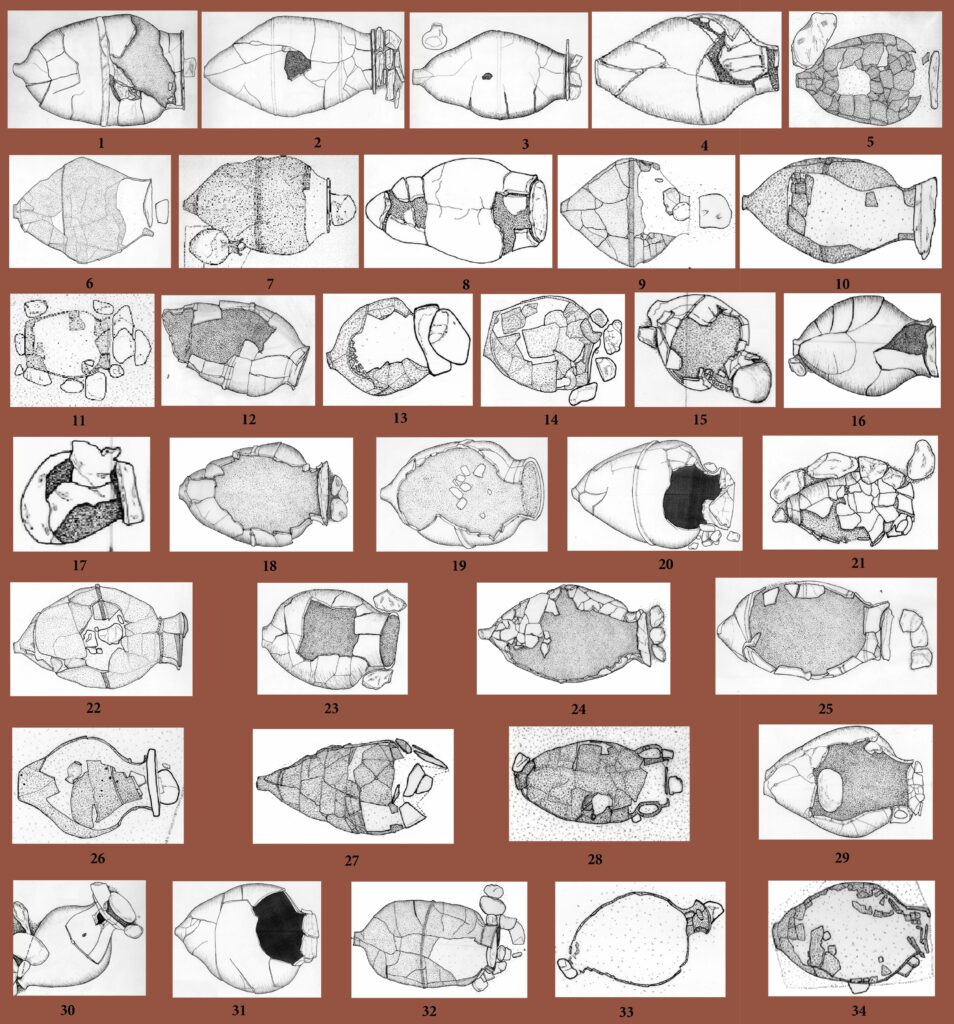

This sub-project examined the documentation of ceramic workshops specializing in pithoi in Stamna, focusing on their typology, decoration, and the social status of their owners. The study catalogued 267 pithoi (34 types) (FIG.7) used for funerary purposes, in addition to 40 that served as storage containers. These vessels primarily contained inhumed individuals, with ten tripod-pithoi being used for both inhumations and cremations, each featuring distinct typological elements.

The decoration on Stamna’s pithoi revealed significant cultural insights. The study investigated how these decorative patterns marked a transition from storage vessels to coffins, offering new perspectives on ancient burial practices. The use of pithoi as coffins suggests a symbolic connection between storage and burial practices, reflecting human care and the preservation of the body after death. (FIG.8).

The research delved into various decorative elements, such as rope, plastic, and impressed decorations, to understand their evolving significance. For example, rope decoration imitates attachments used for handling and protection, while changes in pithos typology and decoration reflected broader economic and social shifts of the time. As communal storage practices transitioned to individual wealth accumulation, the demand for large storage pithoi decreased, leading to simpler decorative designs that marked a departure from their traditional role as symbols of economic and social status.

Overall, this sub-project provided a comprehensive analysis of ceramic workshops in Stamna, revealing how the typology and decoration of pithoi were intertwined with cultural practices and social structures. Through detailed documentation and analysis, the study uncovered the multifaceted roles that these vessels played in ancient society, from practical storage to significant burial artifacts, highlighting their importance in understanding the cultural heritage of Stamna.

2nd sub-project | Christakopoulou, G., and H. Simoni, “The ‘Cracking the Code‘ project; Markers of Culture and Networks in Early Iron Age Stamna, Greece,” The 89th Annual Meeting of SAA (Society for American Archaeology) April 17–April 21, 2024, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Our project aimed to make our methodology and anticipated outcomes accessible to a broad scientific audience, extending beyond the European sphere: we utilized contemporary digital techniques for qualitative and quantitative analyses to interpret ceramic artifacts. Specifically, Geographic Information System (GIS) tools were employed to map motif distributions across the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean regions. By examining motif correlations and densities, we sought to uncover spatial trends, while network analysis enabled the reconstruction of crucial social and trade connections in ancient societies.

A critical aspect of our approach was ensuring a well-structured database, a challenge especially pronounced in older excavations lacking digital documentation. This study outlined initial steps in digitizing analog data, laying the foundation for comprehensive GIS applications. Ultimately, our endeavor aimed to reconstruct the historical narrative of the communities associated with this remarkable ceramic heritage.

3rd sub-project | Christakopoulou, G., and H. Simoni, “The ‘Cracking the Code‘ project; Ancient tales from the grave; A quantitative approach to an unknown Protogeometric community,” 30th EAA Annual Meeting in Rome, Italy, 31 August – 3 September 2024.

The third sub-project delved once again into the analysis of the 267 burial pithoi within the cemetery, with a particular focus on quantitative analysis and the application of Geographic Information System (GIS) techniques. By employing georeferencing methods, we meticulously mapped the previously identified clusters and utilized an array of GIS tools, including spatial analysis, spatial statistics, and Kernel Density Analysis (KDA). This rigorous approach enabled us to explore several critical questions:

– Are there discernible differences in burial practices among the various clusters?

– Does the spatial arrangement of pithoi, along with their associated offerings and decorations, imply a hierarchical societal structure?

– Are there any signs of interaction with external communities?

Through this integrative method, we presented a sophisticated framework for the analysis of excavation data, emphasizing the pivotal role of detailed spatial documentation in rescue excavations. This sub-project not only advanced our understanding of the burial practices at the site but also demonstrated the profound insights that can be gained through the application of advanced GIS methodologies in archaeological research.

VI.2 Additional Scholarly Contributions Beyond the Main Project

During my fellowship at CHS, two more articles were prepared for publication in collaboration with Mary Giamalidi, a fellow archaeologist from Princeton University, who was hosted at CHS as a scholar. The research utilized CHS resources extensively to complete these articles. The articles in question are as follows:

2024 | Giamalidi, M., and G. Christakopoulou, “Deathscape planners in Voula, Attica (Greece). Aspects of social structure through spatial planning and burial procedures” [JEMAHS (Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies)(under review)].

2024 | Christakopoulou, G., and M. Giamalidi, “Pictorial representations of a burial complex of vessels in Voula, Attica” (under review).

VI.3 Talks

During my tenure at CHS, I presented a lecture titled “The ‘Cracking the Code’ Project: Providing ‘the Sense of Order’ or Bridging the Gap between Cultures? Evidence from the Stamna Pottery.” The presentation took place at the Harvard Center for Hellenic Studies in Washington, DC on Wednesday, March 20, 2024.

VI.4 Hybrid Round Table Discussion

During my tenure at the CHS, I actively participated in a hybrid round table discussion on “Cultural Heritage Preservation” convened in May. This interdisciplinary event brought together CHS Spring term research fellows and faculty and students from the Department of Geology at the University of Patras. Guided by my collaborator, Helene Simoni, the round table explored critical strategies and challenges in preserving cultural heritage, emphasizing interdisciplinary approaches and collaborative research methodologies.

Acknowledgements

I extend my heartfelt gratitude to Mark J. Schiefsky, C. Lois P. Grove Professor of the Classics and Director of the Center for Hellenic Studies, for his invaluable guidance and support throughout our tenure at CHS. His visionary leadership has been instrumental in shaping our research endeavors and fostering an environment of scholarly excellence.

Special thanks to Caroline Stark, Associate Director of Academic Affairs, whose steadfast guidance and support enabled us to navigate the CHS landscape effectively. Her dedication to our academic growth and development has been truly commendable.

I am deeply indebted to M. Zoie Lafis, Executive Director, and Tamela J. Taylor, Administrative Manager, for their invaluable assistance and consistent support in all aspects of my work. I am also deeply grateful to Olivia Henderson, Programs Coordinator, who was always there to ensure that everything was perfectly aligned with our needs. Her meticulous planning and coordination were essential in facilitating our work and making our experience at the Center for Hellenic Studies seamless and productive.

I am also deeply appreciative of the entire CHS staff (T. Temple Wright, Librarian for Acquisitions, Reference and Visitor Relations, Sophie Boisseau, Cataloging Librarian, John Fletcher, IT Systems Administrator, Tamir Norman, IT Desktop Support Technician, Ruth Taylor, Director of Hospitality and Facilities, Luc Bouchard and Jose Marquez, Buildings and Grounds Maintenance Technician, Anton Jancsik, Chef, Jose Escobar, Lead Line Cook/Chef de Partie, Ada Resendiz, Head Housekeeper, Jenny Flores and Kelly Navarrette, Housekeepers), for their warm hospitality and invaluable assistance. Their unwavering commitment to our academic pursuits created an environment conducive to focused research and scholarly achievement.

Last but foremost in my heart, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the CHS Spring Term Fellows 2023-24 (Helene Simoni, Michiel van Veldhuizen, Konstantinos Karathanasis, Debby Sneed, Alexandra Villing, Alaya Palamidis, Dylan James, Samuel Holzman, Patricia Kim, Julia Sturm) with whom I had the privilege to collaborate. My experience with them epitomized the dual essence of scholarly and human connection. At CHS, I learned firsthand the transformative power of community, where intellectual growth intertwines with personal development. The sense of fellowship and exchange of ideas among fellow scholars not only enriched my research but also deepened my understanding of myself and others. I am sincerely grateful for the opportunity to have been part of such a supportive and inspiring academic community.

Bibliography

Appadurai, A. 1986a. “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. A. Appadurai, 3–63. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Appadurai, A., ed. 1986b. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bapty, I., and T. Yates, eds. 1990. Archaeology After Structuralism: Post-structuralism and the Practice of Archaeology. London: Routledge.

Bintliff, J. 2012. The Complete Archaeology of Greece From Hunter-Gatherers to the 20th Century AD. www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

Boujek, J. 1985. The Anatolia, Anatolia and Europe: cultural interrelations in the second millennium B.C. Praha.

Christakopoulou Somakou, G. 2009. The cemetery of Stamna and the Protogeometric Period in Aetolia/Akarnania. PhD diss., National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Christakopoulou, G. 2016. “The Protogeometric settlement at Stamna, Aetolia. Some thoughts on the settlers’ origin based on the typology of the graves.” In ACHAIOS, Studies presented to Professor Thanasis I. Papadopoulos, eds. E. Papadopoulou Chrysikopoulou, V. Chrysikopoulos, and G. Christakopoulou, 59–76. Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology.

Christakopoulou, G. 2018. To die in style! The residential lifestyle of feasting and dying in Iron Age Stamna, Greece. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.

Christakopoulou, G. 2023. “Geometric decoration of a monumental oinochoe from Achaia, Greece. An interpretative approach using chess-related terminology and metaphors.” Journal of Greek Archaeology 8:171–201.

Cline, H. E. 2014. 1177 B.C. The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Translated into Greek 2019 by X. Magoulas as 1177 π.Χ. ¨Όταν Κατέρρευσε ο Πολιτισμός¨.

Coldstream, J. N. 1968. Greek Geometric Pottery. London: Methuen.

Coldstream, J. N. 1977. Geometric Greece. London: Ernest Benn.

Gombrich, E. H. 1982. Image and the eye: further studies in the psychology of pictorial representation. Oxford: Phaidon.

Hall, S. 1980. “Encoding/decoding.” In Culture, Media, Language, eds. S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, and P. Willis, 128–138. London: Hutchinson.

Hamilakis, Y. 2007. The Nation and its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hamilakis, Y., and A. Anagnostopoulos. 2009. “What Is Archaeological Ethnography?” Public Archaeology 8(2–3):65–87.

Hardenberg, R., M. Bartelheim, and J. Staecker. 2017. “The ‘Resource Turn’. A Sociocultural Perspective on Resources.” In Resource- Cultures. Sociocultural Dynamics and the Use of Resources, eds. K. A. Scholz, M. Bartelheim, R. Hardenberg, and J. Staecker, 13–23. Ressourcen Kulturen 5. Tubingen.

Hodder, I. 1982. Symbols in Action: Ethnoarchaeological Studies of Material Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hodder, I. 1987. “The contextual analysis of Symbolic meanings.” In The Archaeology of Contextual Meanings, ed. I. Hodder, 1–25. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klontza Jaklova, V. 2012. “Aegean Parallels to Carpathian Bronze Age Pendants.” Archaeologica Slovaca Monographiae 13:189–198.

Knodell, A. R. 2021. Societies in Transition in Early Greece. An Archaeological History. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kopytoff, I. 1986. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. A. Appadurai, 64–91. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Kotsonas, A. 2022. “Early Greek Alphabetic Writing: Text, Context, Material Properties, and Socialization.” American Journal of Archaeology 126:167–200. 10.1086/718415.

Kristiansen, K, and T. Larsson. 2005. The Rise of Bronze Age Society: Travels, Transmissions and Transformations. Cambridge.

Langdon, S. 2008. Art and Identity in Dark Age Greece, 1100−700 BCE. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lemos, I. S., and A. Kotsonas, eds. 2020. A Companion to the Archaeology of Early Greece and the Mediterranean. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell.

Mazarakis-Ainian, A. 2020. Όμηρος και Αρχαιολογία. Athens.

Morris, I. 2010. Why the West rules–for now: the patterns of history, and what they reveal about the future. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Papadopoulos, J. 2019. “Object(s)—Value(s)—Canon(s).” In Canons and Values: Ancient to Modern, eds. L. Silver and K. Terraciano, 42–68. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

Pearce, S. 2002. Μουσεία, αντικείμενα και συλλογές. Μία πολιτισμική μελέτη. Trans. L. Yiokas. Thessaloniki. Originally published in English 1992 as Museums, Objects and Collections. A Cultural Study. Leicester University Press.

Robb, J. E. 1998. “The Archaeology of Symbols.” Annual Review Anthropology 27:329–346.

Robb, J. E. 1999. Material Symbols: Culture and Economy in Prehistory. Carbondale, IL: Center of Archaeology Investigation.

Shanks, M., and C. Tilley. 1987a. Reconstructing Archaeology: Theory and Practice. Cambridge.

Shanks, M., and C. Tilley. 1987b. Social Theory and Archaeology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Simoni, H., K. Papagiannopoulos, R. Tsiakiris, and K. Stara. 2022. “Local Resource Management Imprinted in the Landscape. Convergent Evolution in Two Greek Mountain-Plains During the Last Five Centuries.” In Human-made Environments, The Development of Landscapes as Resource Assemblages, eds. M. Bartelheim, L. Garcia Sanjuan, and R. Hardenberg, 53–74. Tubingen University Press.

Simoni, H. 2024. “Cracking the Code; Symbols, meanings and networks in Early Iron Age Greece. Evidence from the Stamna pottery.” CHS Research Bulletin 12.

Swoboda, E., and P. Vighi. 2016. Early Geometrical Thinking in the Environment of Patterns, Mosaics and Isometries. Springer International Publishing.

Thomas, J. 1996. Time, Culture and Identity: an Interpretive Archaeology. London.

Turner, G. 1992. British Cultural Studies. An Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Whitley, J. 2001. The Archaeology of Ancient Greece. Cambridge University Press.

Whitley, J. 2002. “Objects with Attitude: Biographical Facts and Fallacies in the Study of Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Warrior Graves.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 12:217–232 doi:10.1017/S0959774302000112.

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. This report outlines a collaborative research project with Dr. Helene Simoni. For H. Simoni’s report, see Simoni 2024.