Menelaou, Sergios. "Rethinking Borders in Archaeology through the Eastern Aegean-Western Anatolia Interface." CHS Research Bulletin 13 (2025). https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:106352551.

Early Career Fellow in Hellenic Studies 2024–25

Introduction: What is a border?

Borders are more than mere geopolitical demarcations. They are dynamic, socially constructed processes, produced, contested, and experienced differently across time and space. In the modern world, borders are often embedded in physical infrastructures—walls, fences, checkpoints. In antiquity, however borders were rarely so visible. Instead, they were created through interaction, were shaped by movement, and expressed in material culture. [1]

Archaeology has traditionally lagged behind other disciplines in reconceptualizing borders in this way. While anthropology, geography, and political science have moved toward more fluid, critical interpretations, archaeology has often retained essentialist assumptions, equating material styles with discrete cultural or ethnic groups. [2] In this report, I argue that we must rethink archaeological approaches to borders. Drawing on my recent project, funded through a CHS Early Career Fellowship in Hellenic Studies in Greece and Cyprus, and specifically on the case study of the eastern Aegean–western Anatolia interface, [3] I propose that ancient borders functioned less as lines of division but as zones of convergence and negotiation, and must be understood as dynamic processes that intersect with questions of mobility, connectivity, and identity. I explore how such borders actively shaped cultural identities through the assimilation and adaptation of external elements, resisting models that view island communities as passive peripheries of dominant mainland cultures. Instead, I adopt a framework that sees borderzones as dynamic and creative spaces, formed through mutual engagement rather than unilateral influence.

Rethinking borders: Theoretical frameworks and disciplinary shifts

Scholars have long debated the nature of borders. While terms such as “boundary,” “frontier,” and “borderland” are often used interchangeably, they reflect different conceptual frameworks. Boundaries typically refer to abstract limits, frontiers evoke expanding peripheries, and borderlands emphasize zones of interaction and hybridity. [4]

In archaeology, early models—especially those rooted in the culture-historical tradition—tended to view material culture as a direct expression of ethnic or political identity. These models implied that ceramic styles, burial customs, or architectural forms were often assumed to delineate fixed cultural boundaries. [5] Such approaches have rightly been criticized for projecting modern nationalist frameworks onto ancient contexts.

More recent theoretical advances, especially those influenced by postcolonial theory and network analysis, have challenged this static view. Scholars now increasingly emphasize: cultural entanglement, [6] social and material hybridity, [7] and the agency of individuals and communities in border contexts. This reconceptualisation allows for more nuanced, bottom-up interpretations of borders, not as impermeable lines but as relational, historically situated spaces.

Methods and cautions

A key challenge in the archaeology of borders is methodological: how can we detect ancient boundaries when written sources are absent and material evidence is fragmentary or ambiguous?

As I outline in a recently published chapter, [8] drawn on research developed over the course of this fellowship, archaeologists often rely on the distribution of artefacts—especially ceramics—to infer cultural or political boundaries. However, this practice risks correlating stylistic variation with ethnic difference or political separation. Pottery styles may reflect taste, trade, technological choice, or social status; not necessarily ethnic identity. Similarly, burial customs or settlement patterns may reflect religious affiliation, kinship, or environmental adaptation, rather than geopolitical structures. To avoid these risks, archaeologists must integrate multiple lines of evidence (environmental, technological, spatial), avoid typological determinism, and interpret material culture in its broader social and historical context. In my work, I advocate a multi-scalar and contextual approach, combining site-level analysis with regional and interregional comparisons, and integrating scientific techniques such as ceramic petrography, elemental analysis, and GIS spatial analysis.

Eastern Aegean–Western Anatolia borderzone: A case study in fluidity

The region between the eastern Aegean islands (e.g., Samos, Chios, Lesbos) and the western Anatolian coast presents an ideal case study for rethinking archaeological borders. Today, this maritime space forms a sharp geopolitical divide between Greece and Turkey. But in antiquity, the Aegean was not a border—it was a bridge, a borderzone or interface: a space of contact, not separation.

While in the modern era, the sea forms a national border between Greece and Turkey, in antiquity it enabled cultural exchange, migration, and interaction. From the Neolithic through the historical periods, this region was characterized by sustained interaction. Communities on both sides shared technologies, artistic styles, architectural forms, comparable ceramic traditions, and other crafts, as well as evidence of exotica and ‘foreign’, non-local artefacts.

Yet modern politics have reimagined this region in binary terms. Following the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Aegean was redefined as a national frontier. Greece and Turkey developed divergent archaeological traditions: Greek archaeology emphasized the Aegean’s Hellenic identity, while Turkish archaeology framed Anatolia as an indigenous Turkish cultural space. These nationalist narratives shaped fieldwork, funding, institutional access, and interpretive frameworks. As I argue, they have distorted our understanding of prehistoric dynamics in the region by projecting modern identities onto ancient communities. Foreign archaeological missions, often aligned with nationalist agendas, reinforced these divisions. This divide produced asymmetries in research access, data collection, and publication, while reinforcing ethnic and political binaries that obscure the region’s historical cosmopolitanism. Terms like “Aegean” and “Anatolian” are still too often deployed as ethnic markers, despite the fluid, composite nature of ancient societies.

Interpretive frameworks in archaeology of the region

In my chapter, I outline three key interpretive frameworks that have shaped archaeological thinking in this borderzone:

- Cultural koine models: These empasize shared material traits, e.g. ceramic styles or architectural elements, as evidence of a culturally unified sphere. [9] Scholars have pointed to a sense of homogeneity in the 4th–3rd millennium BC. However, this view may obscure regional diversity and oversimplify patterns of interaction.

- Core-periphery and diffusionist models: Drawing on world-systems theory, [10] these models interpret innovation and cultural change as a result of influence from more “advanced” core areas (e.g. Crete, the Greek mainland) onto peripheral regions like the eastern Aegean islands. The sea is seen here as a barrier, and interaction is often described in terms of passive reception rather than active exchange. This view tends to reproduce colonial hierarchies, positioning local communities as recipients rather than participants in cultural production. It also reflects nationalist narratives that map modern political identities onto ancient geographies.

- Interaction and hybridisation models: In contrast to the above, contemporary scholarship increasingly views the eastern Aegean-Anatolian region as a dynamic contact zone, where cultural exchange led to innovation, adaptation, and hybridity. This model acknowledges the active role of local agents in selecting, modifying, and integrating external influences into their own traditions. In this framework, archaeologists interpret material similarities not as evidence of domination or imitation, but as expressions of connectivity. [11] For example, the presence of Minoan or Mycenaean pottery on the Anatolian coast does not necessarily imply colonization but may reflect selective appropriation, trade, or stylistic adaptation. This approach moves away from binary notions of core and periphery and instead focuses on micro-regional dynamics, emphasizing the permeability and variability of cultural boundaries.

Methodological integration and project approach

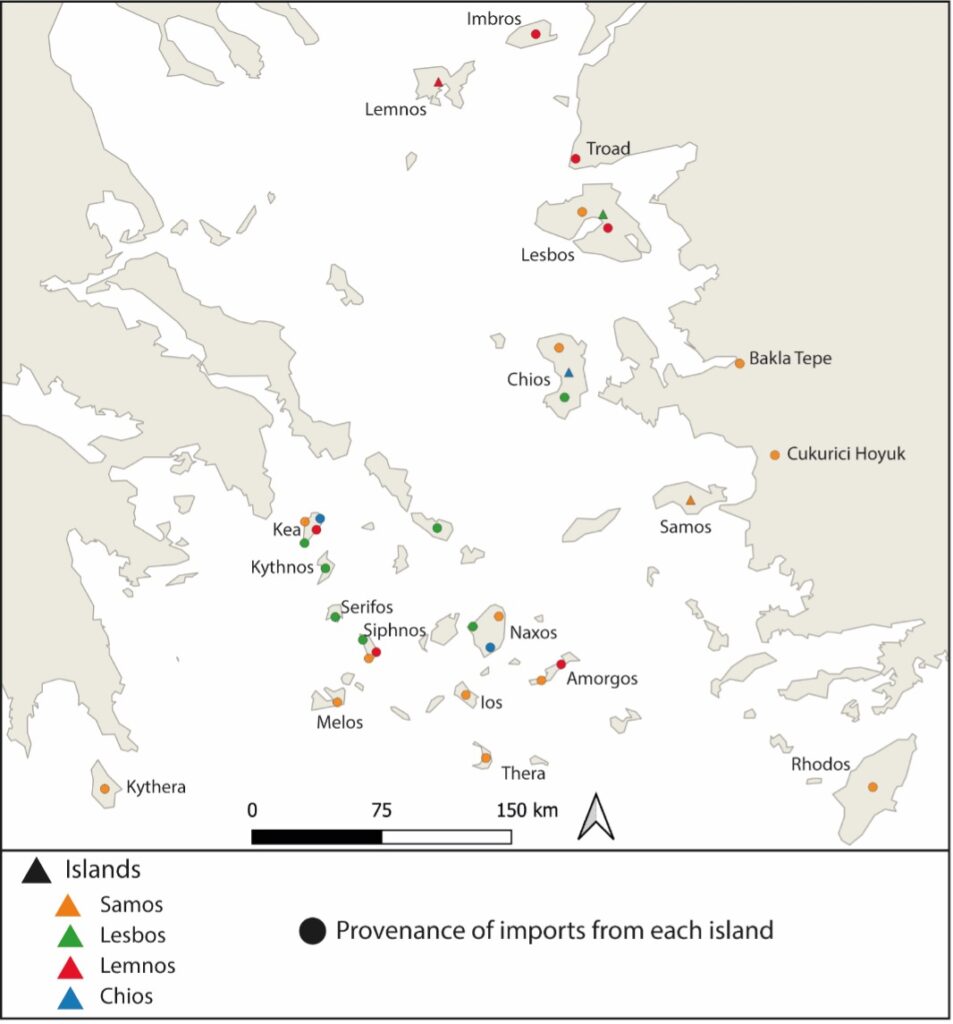

Building on the foundation of prior work, [12] this research project was a multifaceted endeavor. It aimed to contextualize the data collected from the northeast Aegean islands by expanding the study to key sites in the southeast Aegean, as well as Western Anatolia, with a particular focus on the site of Troy. Pottery, a pivotal element of material culture in this era, is employed as a powerful proxy for tracing interconnections and as an embodied source of ideological and technological transmission. Stylistic and typological ceramic affinities have often been considered the primary evidence for identifying connections between different regions, often attributed to trading activities. The research methods I employed reflect the theoretical shift mentioned above. My project combined traditional archaeological survey and ceramic analysis with advanced archaeometric techniques. Specifically, ceramic petrography and elemental analysis are used to trace provenance and exchange patterns on the islands of Lemnos, Lesbos, Chios, Samos, and Troy (Figure 1), during the 3rd millennium BC, and these connections were visualized through spatial analysis to reconstruct interaction networks in the region. [13] The aim was not to map ancient boundaries, but to question how those boundaries were constituted, perceived, and transformed through interaction.

Conclusion: borders as processes, not fixed boundaries

This project challenges the notion of borders as static or immutable. Instead, it argues that borders are historically contingent, socially constructed and continually reshaped through interaction, memory, and meaning-making. In archaeological practice, this entails moving beyond simplistic associations between material culture and fixed ethnic or political boundaries, acknowledging the limitations and biases of traditional frameworks, and adopting models of hybridity, entanglement, and fluidity.

Drawing on the theoretical foundations and preliminary findings of the CHS project, the eastern Aegean–western Anatolia interface, particularly its northeastern extent, emerges not as a frontier, but a liminal zone. This region was shaped by negotiation, where identities, styles, and practices interwove and reconfigured over time, as reflected in the material culture. Rather than delineating discrete cultural territories, the project interrogates the very concept of boundedness in the archaeological record.

This approach aligns with recent theoretical critiques that question the projection of modern political borders and nationalist narratives onto the ancient world. As recent scholarship has shown, such frameworks often essentialize cultural groups and reinforce previous notions of territoriality. By foregrounding the agency of local communities and the dynamics of interaction, this project reconceptualizes borderlands as spaces of cultural creativity and transformation.

The eastern Aegean/western Anatolia interface exemplifies the complexity and permeability of border zones in both antiquity and the modern times. Studying these regions critically allows archaeology to move beyond reductive narratives and engage with broader contemporary debates on migration, identity, and connectivity. Ultimately, the study of borders should focus not on drawing lines, but on understanding movement, negotiation, and transformation—both in the past and in how we choose to interpret it.

Preliminary outcomes and dissemination

This research project had two primary objectives. Firstly, it aimed to examine and reassess previous views on the increase of ceramic imports, and thus of connectivity and mobility, during the second half of the 3rd millennium BC. Analysis of ceramic assemblages from the sites of Poliochni-Lemnos, Thermi-Lesbos, Heraion-Samos, and Troy, revealed a pattern of connectivity with specific sources not only in the northeast Aegean region, but also with the Cyclades (e.g. Naxos, Kea, Sifnos). More importantly, it appears that these sites shared more or less the same sources of imports, thus pointing to a North-South axis network of mobility. [14] These results will be published in a journal article that will contextualize these ceramic connectivity patterns in the eastern Aegean seaboard. Secondly, the project extended beyond the technical-practical aspects to develop a comprehensive theoretical framework, which formed the basis for a chapter published a few months ago that explored the multifaceted definition of borders and its influence on archaeological narratives in the Greek-Turkish geopolitical zone. [15]

In addition to the publications, I have presented preliminary results of my research in several conferences over the year, including for instance the European Association of Archaeologists held in Rome (August 2024), the Archaeometry conference held at Kalamata (October 2024), and the Ceramic Petrology Group Meeting held at Padova-Italy (February 2025). Finally, I was lucky to present my work at the CHS in Washington in May 2025, where I exchanged views and experiences with the other fellows, both visiting and residential.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the Center for Hellenic Studies for awarding me an Early Career Fellowship in Hellenic Studies. This fellowship was a truly meaningful experience, both academically and personally. I feel privileged and honoured not only to have carried out my research with the support of the CHS, but also to have had the opportunity to visit its headquarters in Washington, D.C., and spend time in its exceptional facilities. Access to Harvard University’s electronic resources greatly enriched my work, while presenting my project and engaging with the CHS community was undoubtedly a highlight. Above all, I am deeply grateful to have felt part of the CHS family, a warm, stimulating, and supportive environment.

Select Bibliography

Anderson, J., and L. O’Dowd. 1999. “Borders, Border Regions and Territoriality: Contradictory Meanings, Changing Significance.” Regional Studies 33 (7): 593–604.

Cornell, P. 2017. “Archaeology and the Making of Cultural Borders. Politics of Integration and Disintegration.” In Cultural Borders and European Integration, ed. A. Mats, 47-51. Göteborg.

Diener, C. A., and J. Hagan. 2012. Borders: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford.

Dommelen, P. van, and B. A. Knapp. 2010. Material Connections in the Ancient Mediterranean: Mobility, Materiality and Mediterranean Identities. London.

Feuer, B. 2016. Boundaries, Borders and Frontiers in Archaeology: A Study of Spatial Relationships. Jefferson, NC.

Gimatzidis, S., M. Pieniążek, and S. Mangaloğlu-Votruba, eds. 2018. Archaeology Across Frontiers and Borderlands: Fragmentation and Connectivity in the North Aegean and the Central Balkans from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age. Vienna.

Kotsonas, A., and J. Mokrišová. 2020. “Mobility, Migration, and Colonization”. In The Wiley Companion to the Archaeology of Early Greece and the Mediterranean, eds. I. Lemos and A. Kotsonas, 217-46. Blackwell.

Langer, C., and M. Fernández-Götz. 2020. “Boundaries, Borders and Frontiers: Contemporary and Past Perspective.” In Political and Economic Interaction on the Edge of Early Empires, D.A. Warburton, 33-47. eTopoi. Journal for Ancient Studies, Special Volume 7.

Lightfoot, K. G., and A. Martinez. 1995. “Frontiers and Boundaries in Archaeological Perspective.” Annual Review of Anthropology 24: 471-492.

Menelaou, S. 2021. “Insular, Marginal or Multiconnected? Maritime Interaction and Connectivity in the East Aegean Islands during the Early Bronze Age through Ceramic Evidence.” In European Islands Between Isolated and Interconnected Life Worlds. Interdisciplinary Long-Term Perspectives, eds. L. Dierksmeier, F. Schön, A. Kouremenos, A. Condit, and V. Palmowski, 131-161. Tübingen.

Menelaou, S. 2024a. Multifaceted Borders: Historical Contingencies and Archaeological Perspectives in Modern Cyprus and the Greek-Turkish Interface. In Navigating Borders: Perspectives on Migration and Identity, ed. O. Lytovka, 68-91. London.

Menelaou, S. 2024b. “Bounded by the sea: Concepts of connectivity and mobility across the border zone of the eastern Aegean Islands and western Anatolia during the third millennium BC.” In Borders and Interaction: Concepts of Frontiers in Archaeological Perspectives, eds. M. Brunner, J. Menne and A. Hafner, 89-99. Universitätsforschungen zur Prähistorischen Archäologie 398. Bonn.

Menelaou, S. 2025. “Crafting choices for pottery-making in prehistoric Thermi-Lesbos, northeast Aegean: manufacturing strategies, emerging complexity and, connectivity.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 120.

Menelaou, S., O. Kouka, N. S. Müller, and E. Kiriatzi. 2024. “Longevity, creativity, and mobility at the ‘oldest city in Europe’: ceramic traditions and cultural interactions at Poliochni-Lemnos, northeast Aegean.” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 16: 179.

Mullin, D., ed. 2011. Places in Between: The Archaeology of Social, Cultural and Geographical Borders and Borderlands. Oxford.

Rice, P. M. 1998. “Contexts of Contact and Change: Peripheries, Frontiers, and Boundaries.” In Studies in Culture Contact: Interaction, Culture Change, and Archaeology, ed. J.G. Cusick, 44-66. Carbondale.

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. cf. Lightfoot and Martinez 1995; Mullin 2011; Feuer 2016; Cornell 2017; Gimatzidis, Pieniążek, and Mangaloğlu-Votruba 2018; Langer and Fernández-Götz 2020.

[ back ] 2. Menelaou 2024a.

[ back ] 3. Menelaou 2024b.

cf. Anderson and O’Dowd 1999; Feuer 2016, 11-23.

[ back ] 5. Menelaou 2024a, 3.

[ back ] 6. Knappett 2011.

[ back ] 7. Knapp and van Dommelen 2010.

[ back ] 8. Menelaou 2024a, 7-8.

[ back ] 9. Menelaou 2021, 142-143 with previous literature on the subject.

[ back ] 10. Rice 1998, 45-47.

[ back ] 11. Kotsonas and Mokrišová 2020.

[ back ] 12. Menealou 2021.

[ back ] 13. Menelaou et al. 2024; Menelaou 2025.

[ back ] 14. Menelaou et al. 2024; Menelaou 2025 (Lesbos); The analysis and publication of ceramic samples from Troy is currently ongoing and is planned for the end of 2025.

[ back ] 15. Menelaou 2024a.