Takeuchi, Kazuhiro. "Towards a New Edition of Decrees of the Athenian Subgroups in IG II/III3." CHS Research Bulletin 13 (2025). https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:106297747.

I. New Edition of Post-403 BCE Attic Inscriptions

My research project entails the preparation of a fascicle containing inscribed decrees for the third edition of post-403 BCE Attic inscriptions in the Berlin Academy’s series, Inscriptiones Graecae, volumes II and III (IG II/III3). The second edition, published by Johannes Kirchner during World War I in 1916 (IG II/III2 pars I, fasc. 2), has surpassed the century mark. It encompassed 104 decrees originating from various Athenian subgroups, including tribes, demes, phratries, gene, Tetrapolis and Mesogeioi. However, archaeological excavations conducted in the Athenian Agora and Attic countryside have unveiled numerous additional inscriptions over the past century. The majority of these new discoveries have been documented in the series, The Athenian Agora and Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum (SEG). It is crucial to acknowledge that the second edition heavily relied on squeezes (paper impressions) and that many inscriptions have not been examined through direct inspection (autopsy) since Ulrich Köhler, the editor of the first edition of IG II, published his volumes in 1877 (pars I. Decreta) and 1895 (pars V. Supplementa). Consequently, the previous editions have become outdated due to recent discoveries and advancements in the field of Greek epigraphy.

Prior to the formation of the international team in 1999, the principles for the new edition were firmly established. [1] In addition to adhering to these principles, careful autopsies of inscribed stones and the creation of transcripts (apographa) are essential for securing the exceptional quality of the new edition. This process serves as both a starting point and a foundation for confirming the readings and editing the entries. Furthermore, conducting through investigations and research on old publications, particularly 19th-century Greek journals, and delving into old archives, such as transcripts and notebooks belonging to travelers, archaeologists, and epigraphists, are crucial steps in this undertaking. We acknowledge the shortcomings of the second edition, particularly concerning significant information about the locations where the inscriptions were discovered and early readings.

As already known, the third edition of Inscriptiones Atticae Euclidis Anno Posteriores (IG II/III3) is divided into eight distinct parts. The first part, Leges et decreta, prioritizes the publication of the Athenian laws and decrees. The fourth part, Dedicationes et tituli sacri, encompasses public and private dedications, all of which were completed by Jaime Curbera in 2015, 2017, and 2019. Notably, the first fascicle of the eighth part, Defixiones, contains the long-awaited Attic curse tablets, which were just published in 2024. The Parthenon inventory lists from the fourth century BCE are scheduled for publication in the near future, as one of the second part, Tabulae magistratuum.

In relation to my research, the first part, Leges et decreta, comprises nine fascicles. An international team has dedicated their efforts to this part, and to date, three of the nine fascicles have been published in 2012, 2012, and 2015. As the original editors have stepped back, younger scholars have assumed the task of completing the remaining fascicles. This is also the case for me. In October 2022, the editorial board of the third edition requested that I revitalize the preparation and editing of the ninth fascicle. I officially assumed this role from the previous editors in June 2023.

II. Decrees of the Athenian Subgroups in IG II/III3

The revised edition aims to enhance our understanding of the historical development of Athens and Attica. It delves into the organizational structures and activities of polis subgroups and the Athenian practices pertaining to the formulation and implementation of decrees. Decrees hold immense historical significance, providing direct information about the decisions made by the citizen assembly. These historical records offer invaluable insights into the political and social fabric of ancient Athens. [2]

The ninth fascicle, Decreta tribuum, demorum, phratriarum, gentium, et tetrapolitarum, encompasses all decrees of the Athenian subgroups from the beginning of the fourth century BCE to the end of the first century BCE. Due to the limited availability of decrees from the Attic demes prior to the fourth century BCE, [3] this fascicle provides a comprehensive and detailed analysis of the Athenian subgroups, both diachronically and synchronically. Additionally, it includes an optional category for decrees of dubious or uncertain origin, designated as Decreta generis dubii et incerta . Daria Russo’s monograph, which lists the epigraphical sources for each Athenian subgroup except gene, is useful. [4]

I. Decreta tribuum (approximately 80 tribal decrees): The ten new tribes introduced by Kleisthenes played a pivotal role in the institutional, religious, and military organization of the Athenian polis. Each tribe possessed shrines dedicated to their eponymous heroes, particularly on the Akropolis, where numerous tribal decrees have been unearthed. Notably, several tribal decrees date back to the commencement of the fourth century BCE. Recently, Sophia Alipheri revisited the decree of Pandionis with a dedication (SEG LXV 135).

II. Decreta demorum (approximately 135 deme decrees): The 139 demes constituted the fundamental units of Ancient Attica. Each deme possessed its own assemblies, officials, and priests. Remarkably, some demes even had their own theatres and hosted the dramatic festival known as the Rural Dionysia. [5] A substantial number of honorific decrees originated from these demes. A significant proportion of deme decrees are concentrated in two locations: 19 from Eleusis and 37 from Rhamnous. This concentration is attributed to their religious and military significance within the polis, as well as the extensive archaeological excavations conducted in these areas. [6] Georgios Steinhauer published new deme decrees from Acharnai (SEG XLIII 26), Halai Aixonides (SEG XLIX 141, 142, 143; SEG LIX 142), and Euonymon (SEG LVII 125). Alipheri reedited old deme decrees from Eleusis (SEG LIX 143) and Ikarion (SEG LXIII 105). Furthermore, Angelos Matthaiou published the joint decree of Kydantidai and Ionidai (SEG XXXIX 148) and reedited the decrees of Kollytos and the polis (SEG LVIII 108).

III. Decreta phratriarum (approximately 9 phratry decrees): The phratries played a crucial role in certifying young men for citizenship, implying that all Athenian citizens were likely members of phratries. The phratry decrees of the Demotionidai (IG II/III 2 1237) and the Dyaleis (IG II/III 2 1241) continue to attract attention. [7] However, we only know the names of nine or ten phratries. The primary challenge lies in the loss of half of the phratry decrees. I will continue my research and will examine the squeezes and early transcripts to retrieve the missing information.

IV. Decreta gentium (approximately 25 genos decrees): The gene played a role in Ancient Athens in selecting priests and priestesses for public cults. The precise number of gene is uncertain, but Robert Parker’s work enumerates 47 ‘certain and probable gene’ and 35 ‘uncertain and spurious gene’. [8] Notably, two Eleusinian gene, the Kerykes and the Eumolpidai, and the Salaminioi have issued a substantial number of decrees. The four decrees of the Mesogeioi were separately classified as Decreta Mesogiorum in earlier editions (IG II/III2 1244, 1245, 1247, 1248), but scholars now recognize them as a genos. Georgia Malouchou has conducted a comprehensive study of the Mesogeioi inscriptions. [9]

V. Decreta tetrapolitarum (2 Tetrapolis decrees): The Tetrapolis was an ancient association comprising four demes within the Marathonian region. Given the absence of a decree from the constituent demes, their collective identity as an association was exceptionally robust. Peter Wilson and I have argued that the recently published honorific decree of the Tetrapolis (I.Rhamnous 402) provides the first evidence of a Dionysia held by a corporate body larger than a single deme in Attica. [10]

III. Case Study for Revising a Deme Decree

The majority of decrees from the Attic subgroups were issued in honour of citizens who had made significant contributions to administrative and religious activities. In contrast, there was a separate group of deme decrees that regulated the audit of local officials. This procedure, known as euthynai, were paralleled with the polis institution. At the end of their term of office, officials were subject to legal and financial examinations for any misconduct. [11]

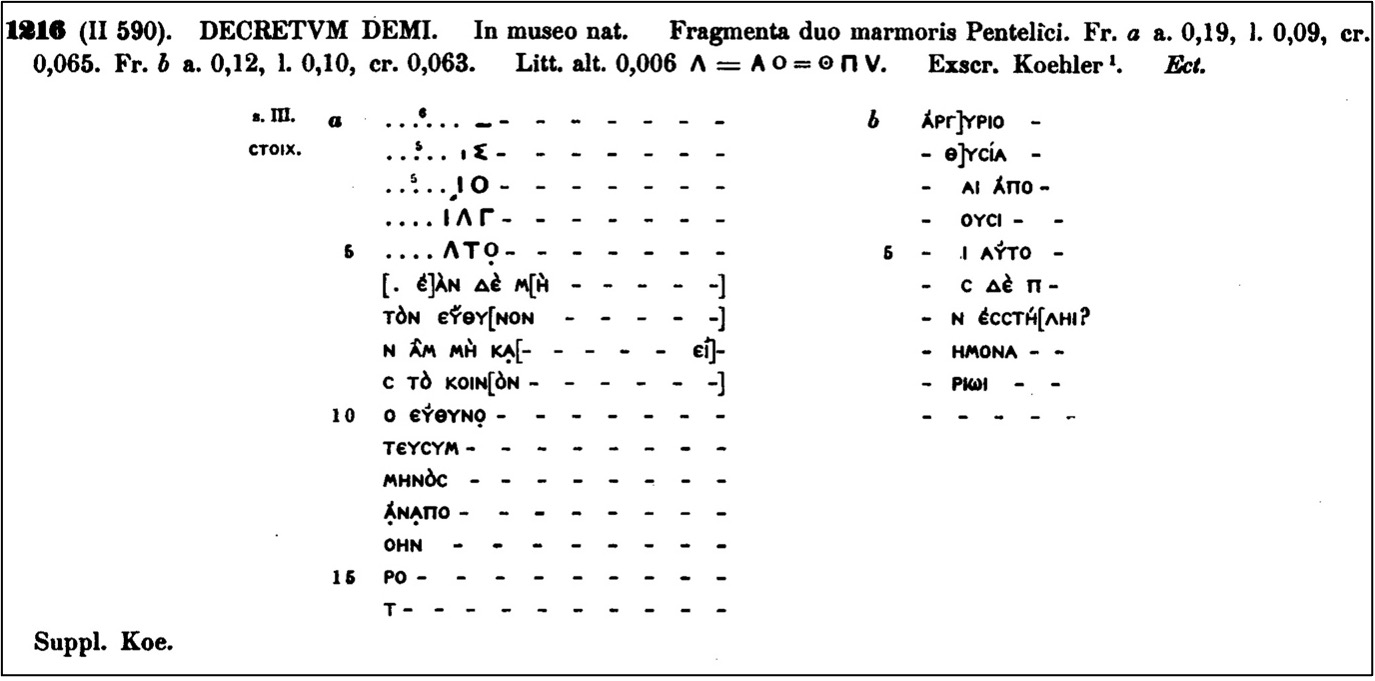

As we can see above, IG II/III2 1216 is one of the deme decrees regarding the euthynai and contains two small fragments a (EM 7729), b (EM 7730) of a white marble stele. [12] The findspot and name of the deme are unknown. The letter form suggests a dating to the third century BCE, as alpha lacks a crossbar, theta has no central dot, and upsilon typically consists of two strokes. I will focus on line 11 of fragment a. Köhler transcribed the stone in Athens and printed the majuscule letters as  without any restoration, as it appears nonsensical. This was followed by kirchner’s edition, which based on the squeeze preserved in Berlin. He printed minuscule text τευσυμ without commentary.

without any restoration, as it appears nonsensical. This was followed by kirchner’s edition, which based on the squeeze preserved in Berlin. He printed minuscule text τευσυμ without commentary.

An autopsy of the stone may provide a potential explanation. I can confirm a circular trace instead of sigma. It is possible that Köhler interpreted a lower slanting trace as part of sigma. However, I believe it is not the trace of a letter but rather a sign of damage. The squeeze at the Institute for Advanced Study (accessible online) appears to suggest that the letter might be sigma, while a bottom curve is discernible in another squeeze at the Houghton Library of Harvard University (at autopsy on May 2025). Kirchner’s reading was undoubtedly influenced by the Berlin squeeze.

My transcript contains  , which I interpret as [κα]|τευθυν̣–. In this inscription, the theta lacks a central dot, and the final letter is more likely to be nu rather than mu. Based on this observation, I propose the verb κατευθύνω, as suggested by LSJ9 s.v. I 3, which translates to ‘κ. τινός demand an account from one, condemn’. LSJ9 cites an example from Plato (Lg. 945a), establishing a close connection between this verb and the noun ὁ εὔθυνος, meaning ‘auditor’ (cf. LSJ9 s.v. II). Markedly, LSJ9 provides a ‘probable’ example from the deme decree IG II/III2 1183 (RO 63) of the late fourth century BCE. My text (autopsy) is:

, which I interpret as [κα]|τευθυν̣–. In this inscription, the theta lacks a central dot, and the final letter is more likely to be nu rather than mu. Based on this observation, I propose the verb κατευθύνω, as suggested by LSJ9 s.v. I 3, which translates to ‘κ. τινός demand an account from one, condemn’. LSJ9 cites an example from Plato (Lg. 945a), establishing a close connection between this verb and the noun ὁ εὔθυνος, meaning ‘auditor’ (cf. LSJ9 s.v. II). Markedly, LSJ9 provides a ‘probable’ example from the deme decree IG II/III2 1183 (RO 63) of the late fourth century BCE. My text (autopsy) is:

κ̣α̣ὶ ἐά̣ν̣ μ̣–

10 [ο]ι̣ δ̣ο̱κεῖ ἀδικεῖν, κατ̣[ε]υ̣[θ]υνῶ α[ὐ]τοῦ [κα]ὶ [τιμήσ]ω οὗ [ἄ]ν̣ μ[ο]ι δ̣ο̱–

κ̣εῖ ἄξιον εἶνα̣ι τὸ ἀδί[κ]ημ̣α·

10 [ο]ι̣ δ̣ο̱κεῖ ἀδικεῖν, κατ̣[ε]υ̣[θ]υνῶ α[ὐ]τοῦ [κα]ὶ [τιμήσ]ω οὗ [ἄ]ν̣ μ[ο]ι δ̣ο̱–

κ̣εῖ ἄξιον εἶνα̣ι τὸ ἀδί[κ]ημ̣α·

‘and if he seems to me [= euthynos] to be in the wrong, I will condemn him at his accounting and will punish him as the wrongdoing seems to me to merit’.

As is widely acknowledged, IG II/III2 1183 offers a crucial piece of evidence that elucidates the practice of deme euthynai and financial administration. [13] An autopsy of the stone comfirms the restoration of the verb κατευθύνω in line 10 (κα[τευθ]υν[ῶ] α[ὐτ]οῦ transcribed by Köhler and subsequently followed by Kirchner based on squeeze and photograph). This sentence indeed represents the oath taken by the euthynos himself. Based on my autopsy and a close parallel from the deme decree, I suggest that the line 11 of IG II/III2 1216 retains part of the verb κατευθύνω, potentially related to the noun εὔθυνος in the preceding line 10.

VI. Next Phase

My primary research focus will gradually shift to the tribal decrees preserved at the Epigraphic Museum, Museum of Ancient Agora, and Archaeological Museum of Elefsina. In particular, I intend to investigate the deme decrees from Eleusis and Rhamnous intensively. Some deme decrees are currently housed in the Louvre (IG II/III2 1174, 1184), the National Museum of Denmark (IG II/III2 1173), and the Hermitage (IG II/III2 1202). Additionally, I should commence preparations for the genos decrees, which are located at the Museum of Ancient Agora and Archaeological Museum of Elefsina. Throughout the final stages of my project, I will consult relevant squeezes in the United States, including Princeton, Berkeley, and Ohio, as well as in Europe, such as Berlin, Oxford, and Cambridge. My ultimate objective is to complete the draft of the ninth fascicle within a four to five-year timeframe.

Acknowledgement: I extend my sincere gratitude to Adele Scafuro, Stephen Lambert, and Sebastian Prignitz for their unwavering support of my project. I am particularly indebted to Angelos P. Matthaiou for his invaluable guidance and editorial supervision. Additionally, I thank Voula Bardani, Georgia Malouchou, and Nicholaos Papazarkadas for their generous cooperation and insightful feedback. For the permission to conduct research on IG II/III2 1216 and 1183, I am grateful to the director and the staff of the Epigraphic Museum. Finally, I would like to express my gratitude to the directors of the Center for Hellenic Studies and the Institute of Historical Research for their funding of this project.

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. A. P. Matthaiou, Horos 13 (1999) 277-280, presents the views of the Greek Epigraphic Society ‘on the new edition of the Attic post Eukleideian Inscriptions’.

[ back ] 2. Cf. S. D. Lambert, Inscribed Athenian Laws and Decrees 352/1-322/1 BC: Epigraphical Essays, Leiden 2012; idem, Inscribed Athenian Laws and Decrees in the Age of Demosthenes: Historical Essays, Leiden 2018.

[ back ] 3. These include IG I3 244 (Skambonidai), 245 (Sypalettos), 249 (Halai Aixonides), 250 (Paiania), 253-254 (Ikarion), 256 (Lamptrai), 258 (Plotheia), along with 247 (phratry or genos) and 255 (Tetrapolis).

[ back ] 4. D. Russo, Le ripartizioni civiche di Atene: Una storia archeologica di tribù, trittie, demi e fratrie (508/7-308/7 A.C.), Athens 2022.

[ back ] 5. On the deme Dionysia, see K. Takeuchi, Land, Meat, and Gold: The Cults of Dionysos in the Attic Demes (Ph.D. diss. National and Kapodistrian University of Athens), Athens 2019, 125-179; E. Csapo and P. Wilson (eds.), A Social and Economic History of the Theatre to 300 BC II. Theatre beyond Athens: Documents with Translation and Commentary, Cambridge 2020, 1-274.

[ back ] 6. Cf. S. D. Lambert, “The Public Enactments of the Deme Eleusis: Between Mysteries and Military”, in H. Beck and S. Scharff (eds.), Beyond Mysteries: The Local World of Ancient Eleusis, Leiden 2025, 297-317.

[ back ] 7. Cf. M. Polito, I decreti dei Demotionidi/Deceleesi ad Atene IG II2 1237: Testo, traduzione, commento, Milano 2020.

[ back ] 8. R. Parker, Athenian Religion: A History, Oxford 1996, 284-327.

[ back ] 9. G. Malouchou, “Τὸ Ἡράκλειον τῶν Μεσογείων· οἱ ἐπιγραφικὲς μαρτυρίες”, in A. P. Matthaiou and V. N. Bardani (eds.), Στεφάνωι στέφανος: Μελέτες εἰς μνήμην Στεφάνου Ν. Κουμανούδη (1931–1987), Athens 2019, 67-97; cf. Parker 1996, 306-307.

[ back ] 10. K. Takeuchi and P. Wilson, “A New Attic Dionysia: On a Recently-Published Honorific Decree of the Marathonian Tetrapolis”, Logeion 13 (2023) [2024] 1-50.

[ back ] 11. Cf. P. Fröhlich, Les cités grecques et le contrôle des magistrats (IVe–Ier siècle avant J.-C.), Genève 2004, 346-355.

[ back ] 12. For more details, K. Takeuchi, “Notes on Deme Euthynai in IG II2 1216”, forthcoming.

[ back ] 13. For full discussion, K. Takeuchi, “A New Edition of IG II2 1183”, forthcoming; cf. S. Negro, “Decreto attico sui doveri del demarco”, Axon 8 (2024) 1-20.