Nakas, Ioannis. "The maritime cultural landscape of Roman Epirus." CHS Research Bulletin 12 (2024). https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:104824973.

Early Career Fellow in Hellenic Studies 2023-24

1. Introduction

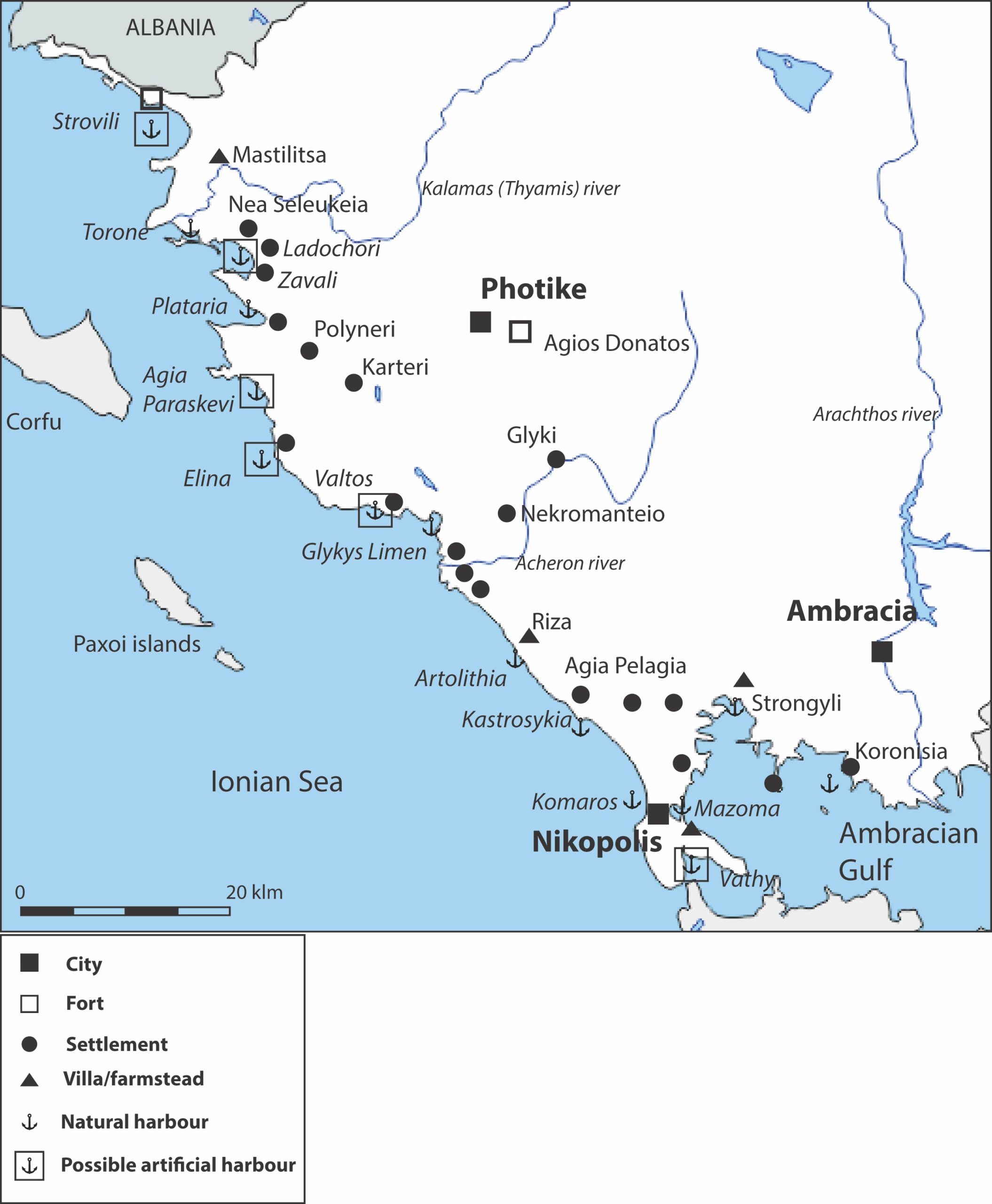

The coastline as a maritime cultural landscape is possibly the most dynamic geographic space related with human activity, an ever-changing natural and anthropogenic landscape and the main interface between the land and the sea. This study, which was generously supported by the Center of Hellenic Studies, deals with a very important and yet hardly studied such landscape, the coasts of Roman Epirus, a region that forms a nodal point along sea and land networks connecting Italy and the Adriatic with Greece and the Levant. It tackles the subject in an interdisciplinary way, bringing together data on seaborne trade, the original configuration of harbors and their ability to accommodate ships, as well as the development of coastal settlements. This study is limited, for practical reasons only, within the borders of modern Greek Epirus, covering the areas between the deltas of Thyamis and Arachthos rivers in the Ambracian gulf (Fig. 1). The time period discussed stretches from the Roman conquest in the early 2nd century BCE until the late Roman Empire in the early 4th century CE. [1]

2. Historical background

The beginning of the Roman period in Epirus is marked by the dramatic events of the conquest by the armies of Aemilius Paulus. Ancient historians vividly document the extent of destruction and subsequent desolation of the Epirotan settlements and countryside. [2] The coastline appears to have initially faced a better fortune, since both the Chaonian tribes in the north and the Cassopaeans in the south did not take part in anti-Roman coalitions and were not punished. But despite this and the fact that new political entities were quickly formed and local coins were re-issued, [3] the impact of the punitive handling of Epirus, as well as the continuous conflicts that took place there in the 1st century BCE (the Mithridatic and Roman Civil Wars), [4] eventually brought their toll on the coastline too. Strabo, writing in the Augustan period, underlines the desolation that prevailed in Epirus in his time. [5]

With the battle of Actium and establishment of the pax romana the need to re-organize urban life in Epirus was evident and Augustus founded Nicopolis, which soon became the biggest city of the region and the province’s capital in the 2nd century CE. Archaeological remains and written evidence also verify the development of new settlements and the foundation of several villas, some belonging to wealthy Roman landowners, like Titus Pomponius Atticus. [6] Nicopolis was frequently visited by Roman emperors such as Nero and Hadrian, who would actively support the city and its hinterlands by funding public works. [7] In 267 CE the Erulians crossed Epirus and besieged Nicopolis, [8] but there is little evidence for extensive destructions. Under Diocletian Epirus was divided into two different provinces, Epirus Vetus with Nicopolis as a capital and Epirus Nova with Dyrrachium as a capital. [9] The end of the Roman period is not marked by any substantial disruption of life in Epirus and especially its coasts.

3. Geomorphology

The coast of Epirus can be divided into two distinctive geomorphological areas: a) Plains and lowlands created by alluvial deposits from large or small rivers and b) steep and relatively high limestone ridges that prevail in the coastline. [10] Alleviation is a great factor of change, especially for the alluvial coasts, whose soil also accelerates subsidence, balanced partly by the constant siltation. In contrast the limestone coasts have remained relatively stable. The issue of sea-level change, which is very important concerning the operation of ancient harbors in general, remains largely unexplored in the region. An average of 2 m rise has been verified in other regions of Greece between the Roman period and today. [11] The general tectonic rise of the limestone areas of the coast has partly balanced this rise, whereas in the alluvial areas subsidence has accelerated it. [12] Archaeological finds, can shed some light on this problem. No fully submerged antiquities have yet been documented in the region, even in areas with antiquities right by the shoreline like Igoumenitsa bay, indicating a rather limited rise. In the case of a Hellenistic fortification wall in the Lygia peninsula, only the bottom row of blocks is partly submerged today, indicating a relative sea-level rise of no more than one meter. [13] The situation is much more complicated in the deltaic and alluvial areas where siltation has considerably affected the development of the coast, as well as the depth of the harbour of anchorages. [14]

4. The coast and its sites

Within the region studied here several geographical units have been distinguished, according mainly to the local geomorphology, which had an important impact in the development of human activities and settlements on the coast (Fig. 1).

4.1. From the borders to Thyamis’ delta

This region forms part of the end of the Akrokeraunia mountains, which fall steeply into the Ionian Sea, forming a series of promontories and deep but small bays, some of which were inhabited in antiquity. Ftelia bay is such a small bay that could offer anchorage to some ships, as also mentioned in recent navigational guides, but there are no reports for any Roman remains. [15] The same stands for the steep, conical Strovili promontory further to the south, which also formed a naturally fortified landmark but does not appear to have been used in the Roman period or earlier. [16]

4.2. Thyamis’ delta

The delta of Thyamis/Kalamas was an area densely populated in the Roman period, as a series of settlements and cemeteries show (Fig. 2). [17] Most of the settlements, however, were not built on the actual coast and were related with agricultural production. Although it is possible that coastal settlements were covered by the ever-changing seafront of the plain, [18] the lack of any more recent settlements, with the exception of Sagiada, also indicates that it was not a favorable area for habitation. A series of bays probably existed along the Roman coast, [19] but these would have likely been shallow and constantly affected by siltation, something that would make them precarious anchorages, as highlighted also by early-20th century navigation manuals. [20]

Nevertheless, the delta gave easy access to the immediate hinterland, where the city of Gitana and other settlements existed. It is unknown whether ships of medium or large capacity could enter the meanders of Thyamis, but lighter and riverboats could easily be employed, as it happened in Roman Tiber. [21] Merchant ships would most likely use the area of the ancient delta north of the Torone peninsula, [22] an area that would have been much more spacious in antiquity and described as a good anchorage by modern navigation manuals. [23] The Hellenistic forts of Pyrgos Ragiou and Lygia were restored during the Roman period, operating most likely as guard posts for the nearby harbour.

4.3. Igoumenitsa bay

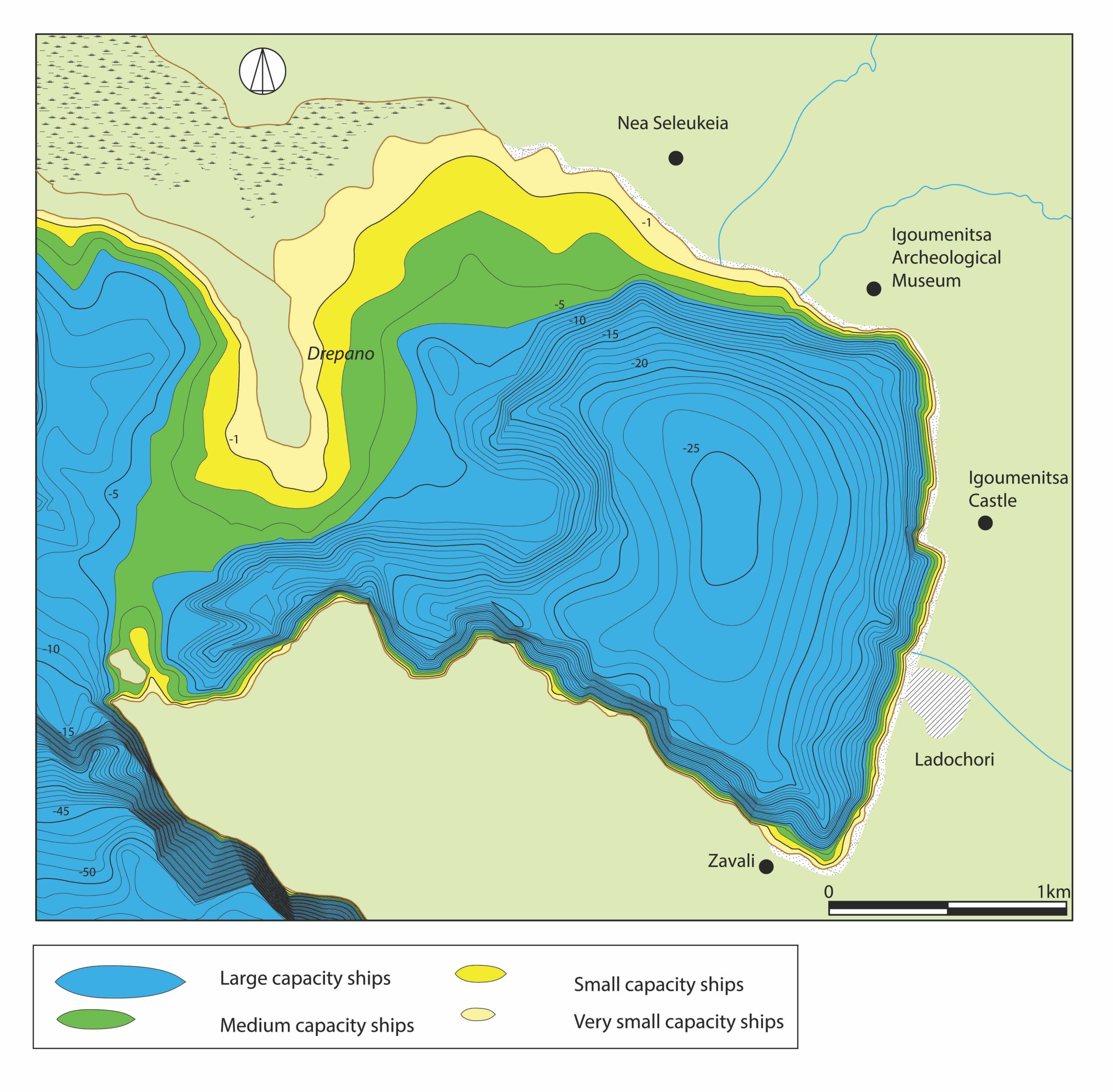

The bay of modern Igoumenitsa was most probably the best anchorage of the region in antiquity, since it was spacious, well-protected, and deep bay (it covers an area of 592 hectares and it was at least 25 m deep and its center in antiquity) with low siltation rates and long beaches along its coast (Fig. 3). The main anchorage was located at the bay’s southern half, the northern one being shallower and muddier due to the proximity of the Thyamis delta. The examination of the bathymetry of the bay shows that a relatively shallow underwater ridge existed between the Drepano sand-spit and the Antimourto cape. [24] This ridge would reach a depth of only 4 m in antiquity and would hinder the entrance of ships of large and very large capacity that would, when loaded, had a draft of 3.5 to 5 m. [25] On the other hand, it would protect the harbor by depleting the force of high incoming waves due to the refraction principle. [26]

The area around the bay of Igoumenitsa flourished during the Roman and Late Roman period. At Nea Seleukeia a Roman villa and a warehouse close to the sea (1st century BCE) indicates that local products were gathered and ships from there, [27] whereas further south, at the Archaeological Museum and the Venetian castle, tombs and architectural remains of the 3rd and 4th century CE show that the main settlement of the area was located there, [28] before it was moved to the most extensive settlement of Ladochori. [29] Ladochori had direct access to the sandy beaches of the bay and buildings of commercial character and workshops have been located in close proximity to the modern waterfront. A series of Norway spruce and maple logs (species common in shipbuilding) preserved by the sea thanks to the waterlogged environment could have been employed for ship construction or repair. [30]

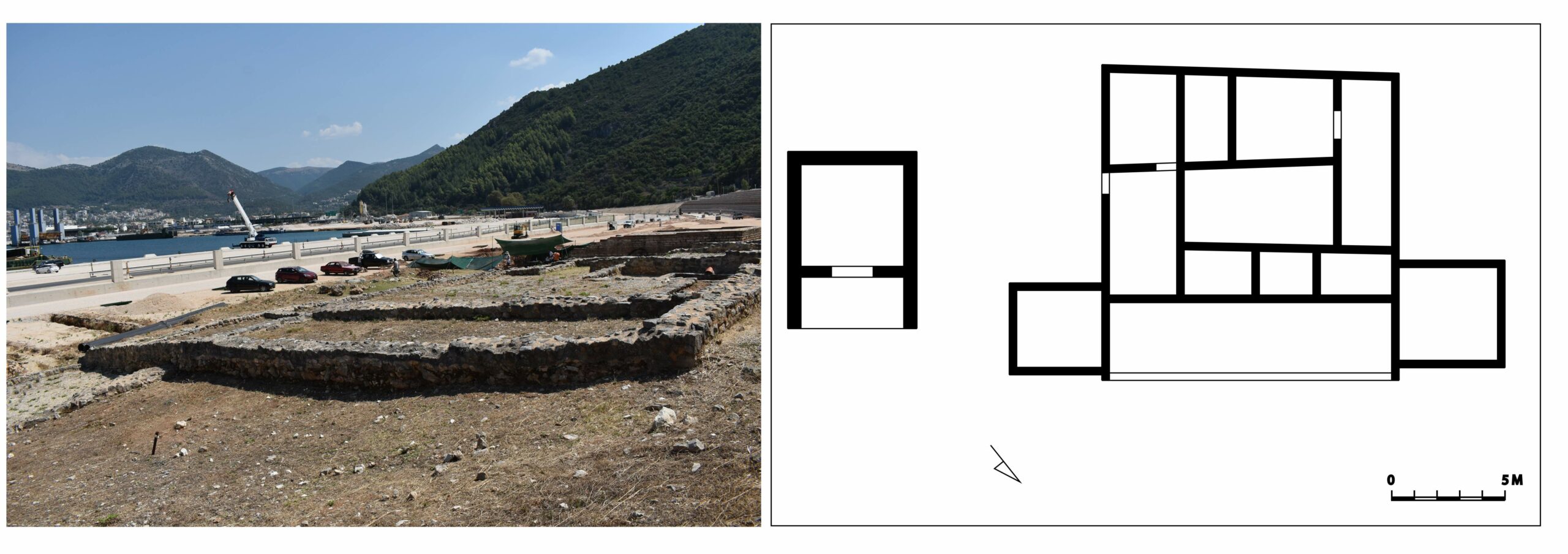

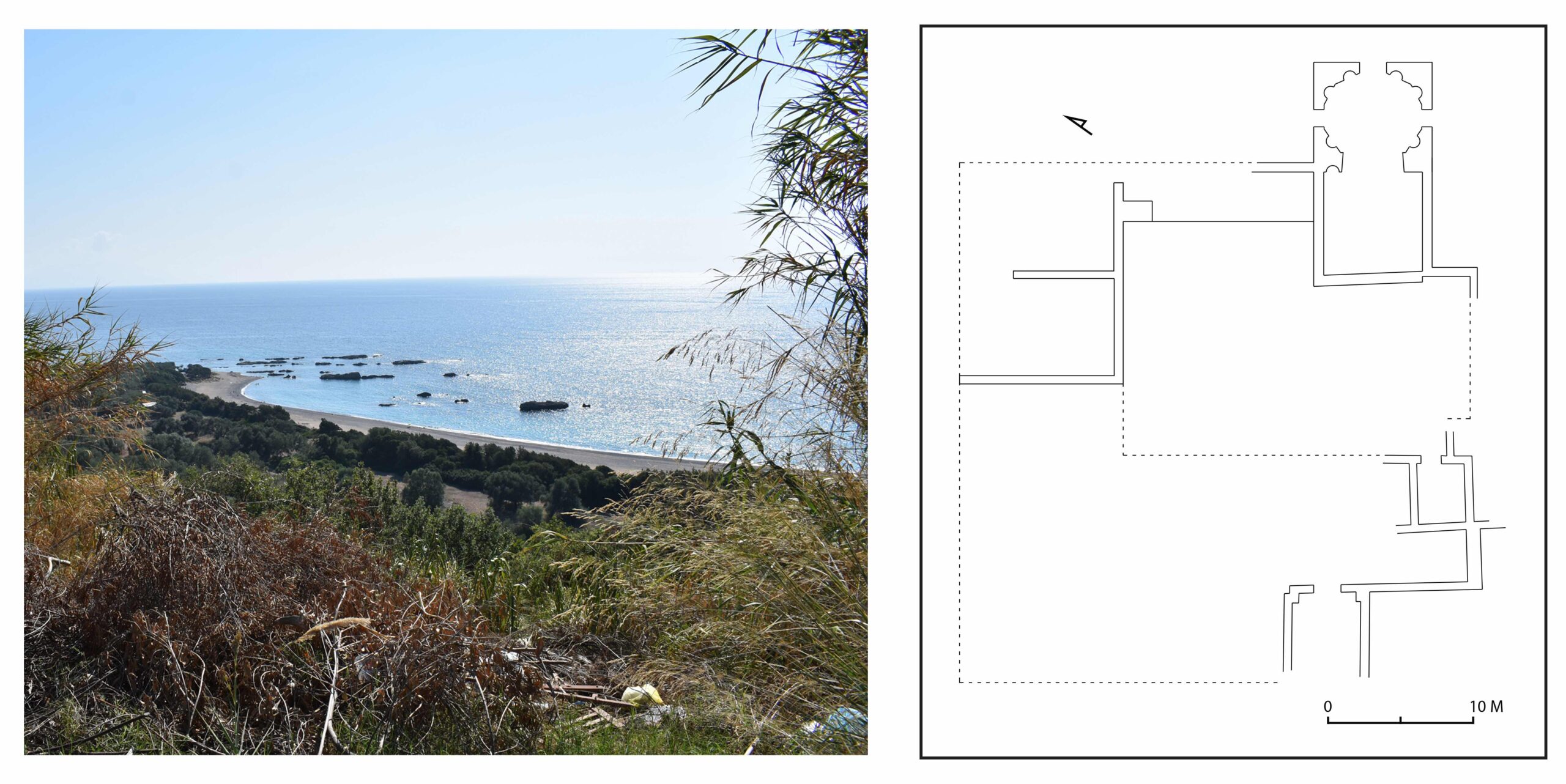

Another important site of Igoumenitsa bay was the 2nd-century CE Zavali villa maritima and its mausoleum (Fig. 4). [31] Located at the bay’s south end it was a relatively small building, standing on a seaside hillock with a portico overlooking the sea, typical characteristics of Roman villas around the Mediterranean (a close parallel is the Strongyli villa near Nicopolis). The imposing brick mausoleum with its high-quality Attic sarcophagi point towards a wealthy individual, possibly a Roman landowner.

4.4. From Igoumenitsa to Parga

The basic characteristic of the coastal region is its steep limestone ridges, interrupted only by small streams and plains and the general lack of ancient settlements, with the exception of the ancient city of Elina (Dymokastro), which stands on a high ridge overlooking the bay of Karavostasi. The Hellenistic settlement, which was inhabited during the Roman period too, [32] had direct access to the open sandy bay below. The existence of an ancient quay in continuation of the city’s fortification walls has been suggested by Dakaris [33] but no actual remains have been observed to confirm this.

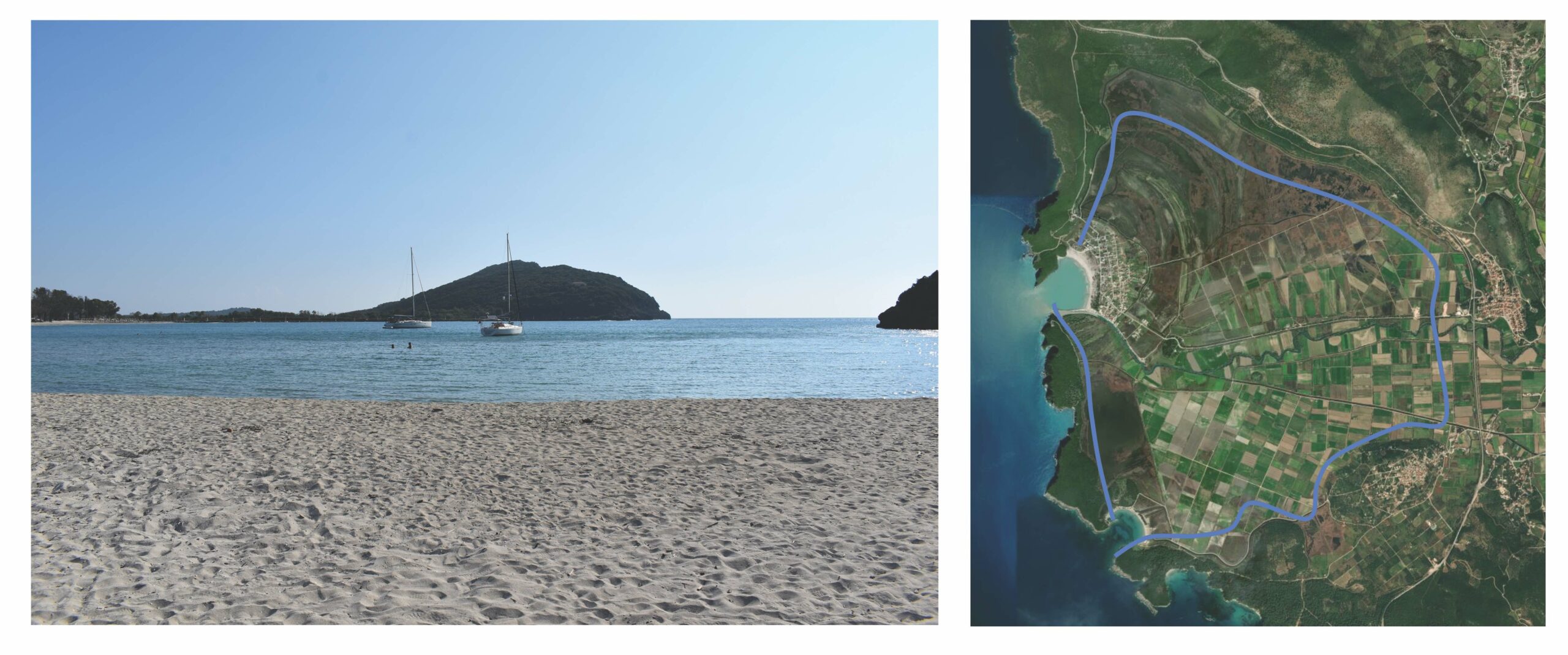

The steep coastline south of Elina offered few natural anchorages [34] and was most likely uninhabited in the Roman period (as it is largely today) and population was gathered in hinterland sites like Agia and Anthousa. [35] The most convenient location for the operation of a harbour was Valtos bay, west of the modern city of Parga, where an ancient stone jetty has been reported, but its existence has not been confirmed. [36] Pottery and commercial amphorae have also been collected by fishermen from the sea. [37] This is probably the bay of Toryne (ladle), which, according to Plutarch, the fleet of Octavian occupied as they came swiftly from Italy in order to face Antonius at Actium later. [38] The sandy bay is well protected thanks to the two natural capes and would offer enough depth and space (c. 28 hectares) for the 200 heavy warships employed by Octavian, as well as access to fresh water. [39]

4.5. Fanari bay and Glykes Limen

Fanari bay, commonly referred by ancient texts as Glykes Limen (sweet harbour, due to the inflow of fresh water from the Acheron river) is today a small sandy bay enclosed by the Agia Eleni and Agios Ioannis ridges. The site was by Cassius Dio as one of the harbours where Octavian sheltered his ships on his way to Actium. [40] Geophysical researches in the region have shown that the actual bay was much larger during the Roman period, covering a total of 1,256 hectares and offering adequate space Octavian’s 200 ships (Fig. 5). [41] Even if the bay was not deep enough for merchant vessels, it was still adequate for galleys whose draft was by definition no more than 1.5 m. [42] The bay communicated with Acheron river, which was most probably navigable in antiquity, at least by small ships and lighters. It remains uncertain whether the Acherusian Lake, which was located very close to the bay, could accommodate any seagoing vessels through the river mouth, which would, more likely, however, avoid venturing into a fresh-water lake whose depth could have been easily affected by siltation.

4.6. From Fanari to Nicopolis peninsula

This part of the Epirus coast is formed by steep limestone with small deep bays opened between them and long stretches of pebble beaches and shoals towards the south. There are few harbours and anchorages there and modern navigation manuals do not mention it as an ideal area for anchoring. An important attribute, however, of the area is the presence of two Roman villas on the hilly coastline facing the sea, located most likely along the ancient coastal road. The villas at Frangokklisia [43] and Agia Pelagia [44] were luxurious establishments equipped with monumental baths and adorned with mosaics and in the case of Agia Pelagia a mausoleum too, similar to the one at Zavali (Fig. 6). Although the two villas cannot be considered villae maritimae, since they are at a distance of 1-2 km from the shore, they form part of the maritime cultural landscape, since they were built with a clear view towards the sea in an idyllic landscape that reminds contemporary frescoes and mosaics. [45] There are no indications of any harbour works related to the villas and it seems probable that only small ships could use the open coastline and be hauled on the long beaches.

4.6. The Nicopolis peninsula

The Nicopolis or Agios Thomas peninsula is a large alluvial area that extends after the end of the limestone coastal ridges. The main characteristic of this area is the low hilly relief and the long sandy beaches on the coast (Fig. 7). The peninsula was densely populated during the Roman period, since, apart from the foundation of Nicopolis in 30 BCE, numerous farmsteads, villas, and settlements were founded around it, whereas the whole area was thoroughly centuriated by the Roman authorities. [46] Naturally the most important settlement was Nicopolis, which was, according to Strabo, served by two harbours, Comarus and Vathy. [47] Comarus is identified with the long open beach that extends north of cape Mytikas to the west of the ancient city (Fig. 8). Despite references to ancient submerged moles there, [48] no actual remains have been located. It appears that Comarus was an open beach where ships would be beached or use lighters and cargoes would enter the city via its monumental western gate, which communicated with the seafront through a paved esplanade adorned with numerous mausolea. [49] Although the choice of Comarus as a harbor seems strange, as it was not protected by any natural or artificial features, it was sheltered by the western and north-western winds that blow in the winter months and allowed ships to avoid the tedious task of passing through the straits of Actium in order to use the other two harbours.

Although not mentioned by Strabo, Nicopolis’ second harbour was most likely the lagoon of Mazoma, immediately to the north-east of the city. Geophysical research has shown that it was much larger and deeper in antiquity (up to 8 m), whereas the sand-spit closing its entrance did not exist (Fig. 7). [50] The calm waters of Mazoma and its proximity to the city made it an ideal anchorage, provided mariners had the time and will to enter the gulf through the straights of Aktion. The importance of this harbor within the urban life and planning of Nicopolis is indicated by the existence of the nearby proastion, an area outside the city walls that accommodated the great theater, the gymnasium, and Augustus’ victory monument on the nearby hill. [51] During the Hadrianic period a massive and luxurious bathhouse was added, its semi-circular facade facing the harbor, [52] which would add to the creation of a proper “harbour scenography”, but would also supply some important infrastructures, including the necessary bathhouse that travelers could visit. No harbour works have been found in the area, apart from possible remains of a stone and concrete quay to the west of the harbor basin, recently located by the author, which appear to correspond to the orientation of the centuriation plan of the area. The calm and protected lagoon would likely not have required any further improvements and mariners could easily drop their anchors onto the muddy seabed and use the soft soil beached around it to unload cargoes.

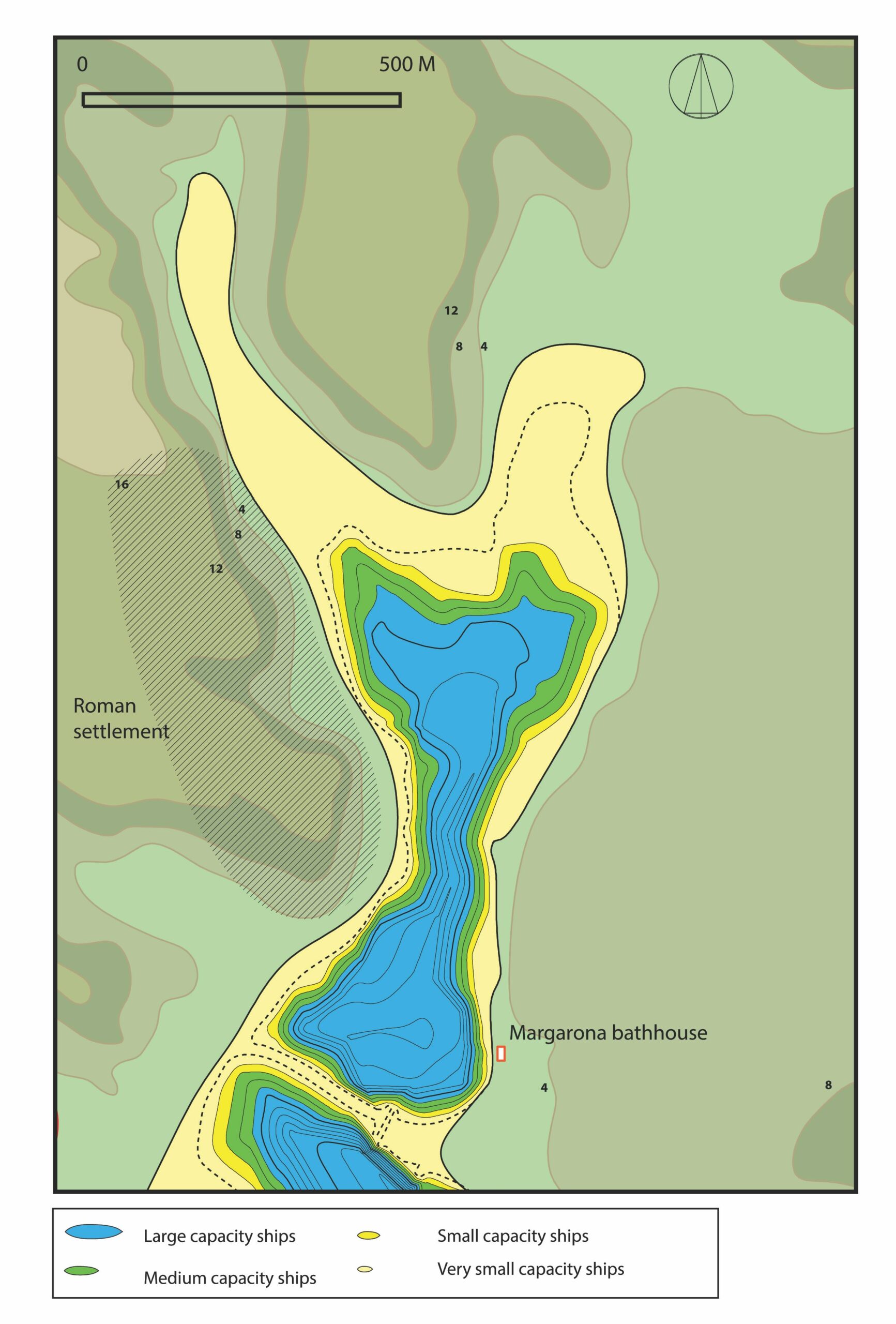

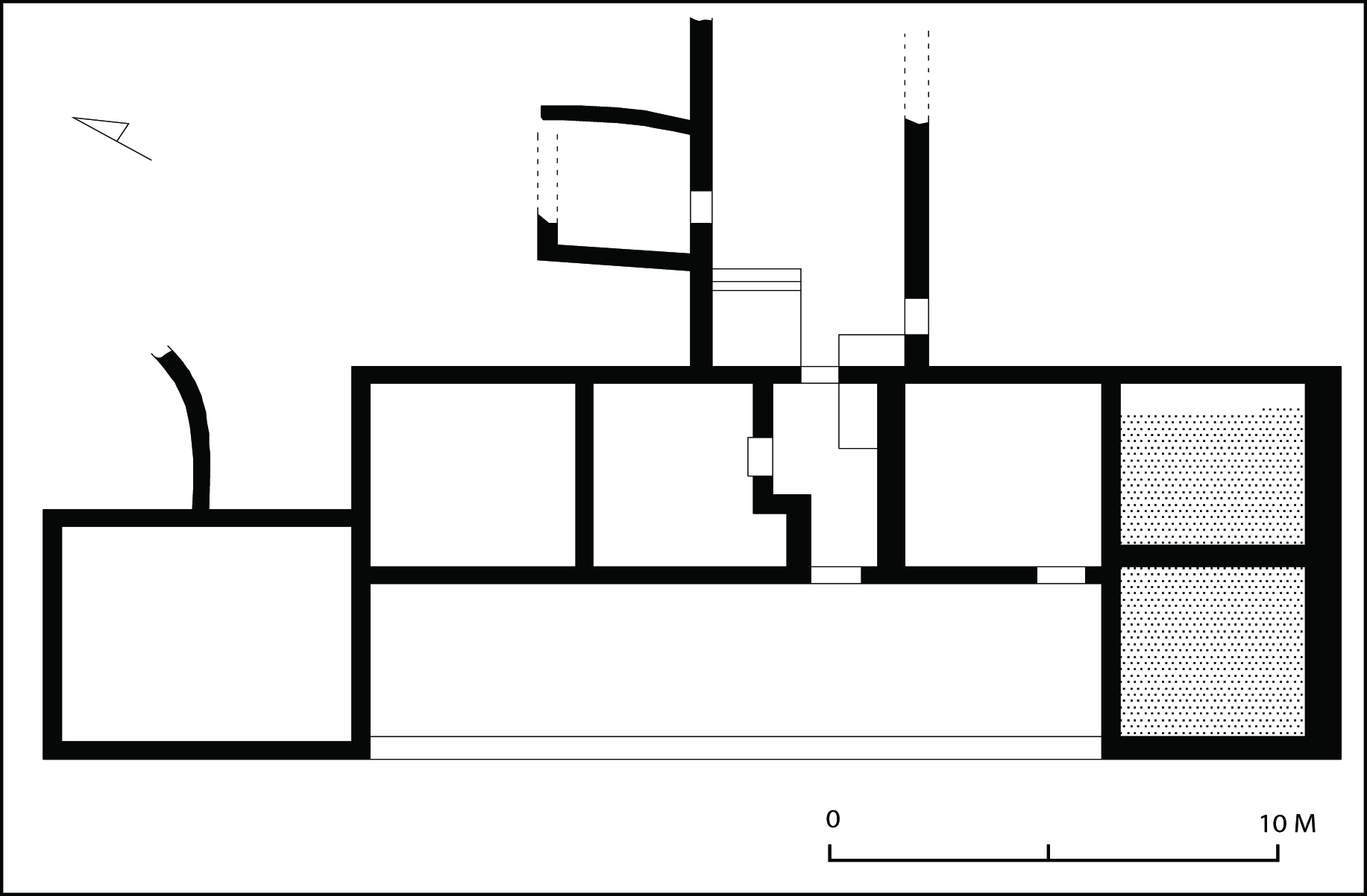

Nicopolis’ third harbour was Vathy (deep), mentioned by Strabo as an excellent anchorage, [53] located at a distance of 3 km southeast of the city. This was a deep and long bay facing south (Fig. 9). The harbor was well-protected from the northern winds, as well as from any ways coming from the south thanks to its narrow entrance [54] and reached a depth of 8 m. [55] The surrounding coasts were generally steep, allowing for the approach of vessels of great draft. Its northern end was a salty marsh, unfit for merchantmen. The bay would have been preferred by the ancient mariners, especially when they needed to spend relatively long periods of time there. Human activity in the area has been confirmed by field survey and has shown that apart from a series of farmsteads and villas a large Roman settlement covered the bay’s western shore (Fig. 7), whereas fishermen have reported pottery finds from the seabed. [56] A large bath complex, possibly dating in the 2nd century CE, is still visible at the harbor’s entrance, at Margarona. [57] The presence of such an impressive building there shows the importance of Vathy as a harbour and the bath was most likely built there to welcome travelers, mariners, and pilgrims who would have arrived there from the south on their way to the city. An additional asset of this specific area is the presence of a fresh-water spring. [58]

4.7. From Nicopolis to the delta of Louros

The area between Nicopolis and Louros river is an extended deltaic wetland, affected heavily by sedimentation from the Louros and Arachthos. Geophysical research has shown that the sea was much further north in antiquity, [59] reaching up to the feet of the limestone ridges and the city of Bouchetion to the north, with several hills being islands in that time. [60] The fertile soil was ideal for cultivation and pasture and a series of farmsteads and villas were built there in the Roman times, the most important of which was the Strongylli villa (1st-3rd century CE). [61] The villa, which stands on a hill overlooking the plain, was similar to the Zavali villa in plan and was also equipped with a large warehouse and a bath that stood nearby (Fig. 10). Even, however, if the sea was much closer in antiquity and the Strongylli hill was an island the villa itself cannot be considered a villa maritima, since it does not face the sea but the nearby hills. It is unlikely that merchantmen would easily approach the above-mentioned zone to load and unload cargoes, due to the small depth and siltation fluctuations of the coast. Smaller vessels would most likely travel and coast and carry agricultural products and people to and from Nicopolis.

5. Conclusions

The coasts of Epirus presented a series of natural harbors of various types that could offer protection to the ships traveling along the coasts, from large and well-protected ones like the bay of Igoumenitsa, Toryne, Fanari, Mazoma and Vathy, which were, however, affected by siltation and were often tedious to approach, to open, silt-free, but less protected bays like Comarus, which, however, allowed for an easy approach and did not force ships to be entangled in secluded spaces. River estuaries were also important in ship traffic along the coasts of Roman Epirus, as indicated by the density of settlements around them, but it is very likely that the mariners would prefer to anchor at their mouths and employ smaller, specialized vessels, as happened between Ostia and Rome. [62] Large part of the coasts belonged to what can be called “opportunistic harbours”, i.e. small natural anchorages with no artificial protective works nor any other infrastructure and serving small communities or villas. [63] In general the coasts of Roman Epirus were far from the deserted country described by Strabo. The number of settlements constantly being documented by archaeological finds shows a dense occupation of various kinds (settlements, forts, villas, cities), especially during the years of the pax romana, which would, inevitably use the sea for trade and transportation and were, not surprisingly, concentrated in areas which combined fertile lands with an easy access to the sea, such as Igoumenitsa bay and the Nicopolis peninsula.

References

Αgalopoulou, P. 1975. “Ανασκαφικές Εργασίες. Νομός Θεσπρωτίας. Λαδοχώρι Ηγουμενίτσας.” [Anaskafikes Ergasies. Nomos Thesprôtias. Ladochôri Êgoumenitsas.] Archaiologikon Deltion 30:239.

Akrivopoulou, E., and K. Lazari. 2005. “Urban organization of a Late Roman Settlement at Ladochori, Igoumenitsa.” In L’ Ilyrrie meridionale et l’Epire dans l’ Antiquite IV, ed. P. Cabanes and J.-L. Lamboley, 407-414. Paris.

Andreou, I. 1979. “Νομός Πρέβεζας. Ανθούσα Πάργας.” [Nomos Prebezas. Anthousa Pargas.] Archaeological Deltion 34:246-247.

Angeli, A., and I Katsadima. 2001. “Riza and Agia Pelagia: Two architectural assemblages of the Roman Era along the Coast of Southern Epirus.” In Isager 2001a:91-108.

Antoniadis, V. 2016. Tabula Imperii Romani. Epirus, Athens.

Aubouin, J. 1959. Contribution a l’etude geologique de la Grece septentrionale: les confins de l’Epire et de la Thessalie. Annales Geologiques de Pays Helleniques 10. Athens.

Beresford, J. 2013. The Ancient Sailing Season. Leiden.

Besonen, M. R. 1997. The Middle and Late Holocene Geology and landscape Evolution of the Lower Acheron River Valley, Epirus, Greece. Master’s Thesis, University of Minnesota.

Besonen, M. R., G. Rapp, and Z. Jing. 2003. “The Lower Acheron River Valley: Ancient Accounts and the Changing Landscape.” In Wiseman and Zachos 2003:199-234.

Boetto, G. 2016. “Portus, Ostia and Rome: A Transport Zone in the Maritime/Land Interface.” In Ancient Ports. The Geography of Connections, Proceedings of an International Conference at the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, ed. K. Höghammar, B. Alroth, and A. Lindhagen, 269-289. Boreas 34. Uppsala.

Bowden, W. 2003. Epirus Vetus. The Archaeology of a Late Antique Province. London.

Bruneau, P. 1981. “Premier propos sur le front de mer: La façade maritime du Quartier du théâtre.” Bulletin de Correspondence Hellenique 105:107–118.

Cabanes, P. 1997. “Από τη ρωμαϊκή κατάκτηση έως τη μεγάλη κρίση του 3ου αι. μ.Χ.” [Apo tê rômaikê kataktêsê eôs tê megalê krisê tou 3ou ai. m.X.] In Ēpeiros, 4000 chronia Hellēnikēs historias kai politismou, ed. M. V. Sakellariou, 115-39. Athens.

Chabrol, A., G. Apostolopoulos, K. Pavlopoulos, E. Fouache, and C. Le Cœur. 2012. “The Holocene evolution of the Kalamas delta (northwestern Greece) derived from geophysical and sedimentological survey.” Géomorphologie 18:45-58.

Chabrol, A., A. Gonnet, E. Fouache, K. Pavlopoulos, and C. Le Cœur. 2022. “Geomorphology of the Kalamas river delta (Epirus, Greece).” Journal of Maps 18:276-287.

Chiotis, A. 1998. “Ένα από τα ψηφιδωτά δάπεδα της ρωμαϊκής βίλλας Στρογγυλής στην Ήπειρο.” [Eva apo ta psêfidôta dapeda tês rômaikês.] Αρχαιολογία 68:79-83.

Chrysos, E. 1981. “Συμβολή στην Ιστορία της Ηπείρου κατά την πρωτοβυζαντινή εποχή.” [Sumbolê stên Istoria tês Êpeirou kata tên prôtobuzantinê epochê.] Ηπειρωτικά Χρονικά [Êpirôtika Chronika] 23:9-111.

———, ed. 1987. Nicopolis I. Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Nicopolis (23-29 September 1984). Preveza.

Chrysostomou, P. 1980. “Νομός Πρεβέζης. Ριζά Πρεβέζης. Αρχαία Κασσωπαία.” [Nomos Prebezês. Piza Prebezês, Archaia Kassôpaia.] Archaiologikon Deltion 35:316-20.

———. 1982. “Το Νυμφαίο των Ριζών Πρεβέζης.” [To Numfaio tôn Rizôn Presbezês.] Archaiologika Analekta ex Athenon 15:10-21.

Dakaris, S. 1971. Cassopaia and the Elean colonies. Ancient Greek Cities 4. Athens.

———. 1972. Θεσπρωτία [Thesprôtia]. Ancient Greek Cities 15. Athens.

———. 1987. “Η ρωμαϊκή πολιτική στην Ήπειρο.” [Hê rômaikê politikê stên Êpeiro.] In Chrysos 1987:1-21.

Delano Smith, C. 1979. Western Mediterranean Europe. A Historical Geography of Italy, Spain and Southern France since the Neolithic. London.

Douzougli, A. 1993. “Ανασκαφικές εργασίες. Νομός Άρτας. Κοινότητα Στρογγυλής.” [Anaskafikes ergasies. Nomos Artas. Koinotêta Stroggulês.] Archaiologikon Deltion 48:282-285.

———. 1994. “Ανασκαφικές εργασίες. Νομός Άρτας. Κοινότητα Στρογγυλής.” [Anaskafies ergasies. Nomos Artas. Koinotêta Stroggulês.] Archaiologikon Deltion 49:382-387.

———. 1998. “Μία ρωμαϊκή αγροικία στις ακτές του Αμβρακικού.” [Mia rômaikê agroikia stis aktes tou Ambrakikou.] Αρχαιολογία [Archaiologia] 68:74-78.

Flämig, C. 2007. “Nicopolis and the Grave Architecture in Epirus in Imperial Times.” In Zachos 2007:227-232.

Fouache, E. 1999 L’alluvionnement historique en Grèce occidentale et au Péloponnèse, géomorphologie, archéologie, histoire. Bulletin de Correspondence Hellenique suppl. 35.

Franke, P. R. 1961. Die antiken Münzen von Epirus. Wiesbaden.

Hammond, Ν. G. L. 1967. Epirus. The Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and the Topography of Epirus and the Adjacent Areas, Oxford.

Institut de Géologie et Recherches du Sous-Sol, Athènes and Institut Français du Pétrole. 1966. Etude geologique de l’Epire (Grece nord-occidentale). Paris.

Ιsager, J., ed. 2001a. Foundation and Destruction, Nikopolis and the Northwestern Greece: The Archaeological Evidence for the City Destructions, the Foundation of Nikopolis and the Synoecism. Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens 3. Athens.

———. 2001b. “Eremia in Epirus and the Foundation of Nicopolis: Models of Civilization.” In Isager 2001a”17-28.

Jing, Z., and G. Rapp. 2003. “The Coastal Evolution of the Ambracian Embayment and Its Relation to Archaeological Settings.” In Wiseman and Zachos 2003:157-98.

Kanta-Kitsiou, A. 2009. Δίκτυο Αρχαιολογικών Χώρων Θεσπρωτίας [Diktuo Archaologikôn Chôrôn Thesprôtias]. Igoumenitsa.

Kanta-Kitsiou, A., O. Palli, and I. Anagnosotu. 2008. Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο Ηγουμενίτσας [Archaiologiko Mouseio Êgoumenitsas]. Igoumenitsa.

Karatzeni, V. 2001. “Epirus in the Roman Period.” In Isager 2001a:164-180.

———. 2011. “Ambrakos and Bouchetion. Two polichnia on the north coast of the Ambracian Gulf.” In L’Illyrie méridionale et l’Epire dans l’Antiquité IV: actes du IVe colloque international de Grenoble, ed. J.-L. Lamboley and M. P. Castiglioni, 146-159.

Karras, C. 1997. “Το Κάστρο των Ρωγών.” [To Kastro tôn Rôgôn] In Ιστορικά Μνημεία της Λάκκας Σούλι, Πρακτικά Ημερίδας, Πρέβεζα [Istorika Mnêmeia tês Lakkas Souli, Praktika Êmeridas, Prebeza], ed. N. D. Karambelas, 97-115. Preveza.

King, C. A. M. 1972. Beaches and Coasts. 2nd ed. London.

Konstantakaki, A. I. 2015. Η Κατοίκηση στα Παράλια της Επαρχίας Παλαιάς Ηπείρου από την Ύστερη Αρχαιότητα έως την Αρχή της Μέσης Βυζαντινής Περιόδου (4ος-8ος Αιώνας) [Ê Katoikêsê sta Paralia tês Eparchias Palaias Êpeirou apo tên Usterê Archaiotêta eôs tên Archê tês Mesês Buzantinês Periodou (4os-8os Aiônas)]. MA Thesis, University of Thessaloniki.

———. 2018. “Παράλιες οικιστικές θέσεις στην περιφέρεια της Νικόπολης.” [Paralies oikistikes theseis stên periferiea tês Nikopolês.] In What’s New in Roman Greece? Recent Work on the Greek Mainland and the Islands in the Roman Period, ed. V. Di Napoli, F. Camia, E. Evangelidis, D. Grigoropoulos, D. Rogers, and S. Vlizos, 21-38. Μελετήματα 80. Athens.

Kotsovilis, N. 1898. Νέος Λιμενοδείκτης [Neos Limenodeiktês]. Athens.

Labrou, V. 2006. “Οικιστική οργάνωση του Θεσπρωτικού χώρου κατά τη Ρωμαιοκρατία.” [Oikisikê organôsê tou Thespôtikou chôrou kata tê Rômaiokratia.] Ηπειρωτικά Χρονικά [Êpirôtika Chronika] 40:257-275.

“Ladochori.” 2012. Οδυσσευς [Odusseus]. Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports. http://odysseus.culture.gr/h/3/eh351.jsp?obj_id=13441.

Lazari, K., A. Tzortzatou, and K. Kountouri. 2008. Δυμόκαστρο Θεσπρωτίας. Αρχαιολογικός Οδηγός [Dumokastro Thesprôtias. Archaiologikos Odêgos]. Athens.

Leidwanger, J. 2013. “Opportunistic Ports and Spaces of Exchange in Late Roman Cyprus.” Journal of Maritime Archaeology 8:221–243.

———. 2020. Roman Seas. A Maritime Archaeology of Eastern Mediterranean Economies. Oxford.

Marriner, N. and C. Morhange. 2007. “Geoscience of Ancient Mediterranean Harbours.” Earth–Science Reviews 80:137–194.

Moore, M. G. 2001. “Roman and Late Antique Pottery of Southern Epirus – Some results of the Nikopolis Survey Project.” In Isager 2001a:79-90.

Morrison, J. S., and J. F. Coates. 1996. Greek and Roman Oared Warships. Oxford.

Nakas, I. 2022. The Hellenistic and Roman Harbours of Delos and Kenchreai. Their Construction, Use and Evolution. Nautical Archaeology Society Monograph Series 6. Oxford.

Papadopoulou, V. 1989. “Νομός Άρτας. Στρογγυλή. Ναός Αγίας Αικατερίνης.” [Nomos Artas. Stroggunê. Naos Agias Aikaterinês.] Archaiologikon Deltion 44:285.

Petsas, F. 1950-51. “Ειδήσεις εκ της 10ης Αρχαιολογικής Περιφέρειας Ηπείρου.” [Eidêseis ek tês 10ês Archaiologikês Perifereias Êpeirou.] Archaiologike Ephemeris 1950/1951:31-49.

Pirazzoli, P. A. 2005. “A Review of Possible Eustatic, Isostatic and Tectonic Contributions in Eight Late Holocene Relative Sea-Level Histories from the Mediterranean Area.” Quaternary Science Reviews 24:1989-2001.

Preka-Alexandri, K. 1995. “Ανασκαφικές Εργασίες. Νομός Θεσπρωτίας. Επαρχία Θυάμιδος. Λαδοχώρι. Οικόπεδο Ντρίτσου.” [Anaskafikes Ergasies. Nomos Thesprôtias. Eparchia Thuamidos.] Archaiologikon Deltion 50:445-446.

Riginos, G. 1992. “Νέα Σελεύκεια.” [Nea Seleukeia.] Archaiologikon Deltion 47:347-348.

———. 1999. “Ανασκαφικές Εργασίες. Νομός Θεσπρωτίας. Δήμος Ηγουμενίτσας.” [Anaskafikes Ergasies. Nomos Thesprôtias. Dêmos Êgoumenitsas.] Archaiologikon Deltion 54:494-502.

———. 2000. “Ανασκαφικές Εργασίες. Νομός Θεσπρωτίας. Δήμος Ηγουμενίτσας. Κάστρο Ηγουμενίτσας.” [Anaskafikes Ergasies. Nomos Thesprôtias. Dêmos Êgoumenitsas. Kastro Êgoumenitsas.] Archaiologikon Deltion 55:656-657.

———. 2003. “Ανασκαφικές Εργασίες. Νομός Θεσπρωτίας.” [Anaskafikes Ergasies. Nomos Thesprôtias.] Archaiologikon Deltion 56-59:287-292.

———. 2005. “Ανασκαφικές Εργασίες. Νομός Θεσπρωτίας. Δήμος Ηγουμενίτσας. Περιοχή Λαδοχωρίου (οικόπεδο ΙΚΑ).” [Anaskafikes Ergasies. Nomos Thesprôtias. Dêmos Êgoumenitsas. Periochê Ladochôrious (oikipedo IKA).] Archaiologikon Deltion 60:568.

———. 2007. “Η Ρωμαιοκρατία στα δυτικά παράλια της Ηπείρου με βάση τα πρόσφατα αρχαιολογικά δεδομένα από τη Θεσπρωτία.” [Hê Pômaiokratia sta dutika paralaia tês Êpeirou me base ta prosfata archaologika dedomena apo tê Thesprôtia.] In Zachos 2007:163-173.

———. 2012. “Εφορεία Προϊστορικών και Κλασικών Αρχαιοτήτων. Πρέβεζα.” [Eforeia Proiostorikôn kai Klasikôn Archaiotêtôn. Prebeza.] In 2000-2010, Από το ανασκαφικό έργο των Εφορειών Αρχαιοτήτων [2000-2010, Apo to anaskafiko ergo tôn Eforeiôn Archaitêtôn], ed. M. Andreadaki-Vlazaki, 355-356. Athens.

Sarikakis, Th. 1964. “Συμβολή εις την ιστορίαν της Ηπείρου κατά τους χρόνους της ρωμαϊκής κυριαρχίας (167-31 π.Χ.).” [Sumbolê eis tên istorian tês Êpeirou kata tous chronous tês rômaikês kuriarchias.] Archaiologike Ephemeris 1964:105-119.

———. 1966. “Συμβολή εις την ιστορίαν της Ηπείρου κατά τους Ρωμαϊκούς χρόνους.” [Sumbolê eis tên istorian tês Êpeirou kata tous Rômaikous chronous.] Ellinika 19:194-215.

Smiris, G. 2004. Το δίκτυο των οχυρώσεων στο πασαλίκι των Ιωαννίνων (1788-1822) [To diktuo tôn ochurôseôn sto pasaliki tôn Iôanninôn]. Ioannina.

Stefanidou-Tiveriou, Th. 2014. “Έκτορος λύτρα. Η σαρκοφάγος από τη Μονή της Αγίας Πελαγίας στην Πρέβεζα και τα αττικά της πρότυπα.” [Ektoros lutra. Hê sarkofagos apo tê Monê tês Agias Pelagias stên Prebza kai ta attika tês protupa.] In ΕΓΡΑΦΣΕΝ KAI ΕΠΟΙΕΣΕΝ: Essays on Greek Pottery and Iconography in Honour of Professor Michalis Tiverios, ed. P. Valavanis and E. Manakidou, 511-524. Thessaloniki.

Stefanidou-Tiveriou, Th., and E. Papagianni. 2015. Ανασκαφή Νικοπόλεως: Σαρκοφάγοι Αττικής και Τοπικής Παραγωγής [Anaskafê Nikopoleôs: Sarkofagoi Attikês kai Topikês Paragôgês]. Athens.

Stein, C.A. 2001. In the Shadow of Nikopolis: Patterns of Settlement on the Ayios Thomas Peninsula.” In Ιsager 2001a:65-79.

Tsoukalas, P. D. 1911. Πλοηγός της Ελλάδος και Κρήτης [Ploêgos tês Ellados kai Krêtês]. Athens.

Ugolini, L. M. 1935. “Nuove Scoperte Della Missione Archeologica Italiana in Albania: La ‘Grande Ercolanese’ Di Butrinto.” Bollettino D’arte Del Ministero Della Pubblica Istruzione 3:68–82.

Ugolini, F. 2020. Visualizing Harbours in the Classical World. London.

Vasileiadis, S., E. Yangoudi, A. Papanastasiou, E. Christodouloy, and L. Liakos. 2008. Ιστορικός και Αρχαιολογικός Άτλας Ελληνοαλβανικής Μεθορίου [Istorikos kai Archaiologikos Atlas Ellênoalbanikês Methoriou]. Athens.

Vasilikou, Ν. 2000. “Νομός Θεσπρωτίας. Περιοδείες-Καταγραφές-Κηρύξεις Μνημείων.” [Nomos Thesptôtias. Periodeies-Kêrukseis Mnêmeiôn.] Archaiologikon Deltion 55:615-618.

Vlachopoulou-Oikonomou, A. 2003. Επισκόπηση της τοπογραφίας της αρχαίας Ηπείρου. Νομοί Ιωαννίνων-Θεσπρωτίας και Νότια Αλβανία [Episkopêsê tês topografias tês archaia Êpeirou. Nomoi Iôanninôn-Thesprôtias kai Notia Albania]. Ioannina.

Vokotopoulou, I. 1969. “Νομός Πρεβέζης. Καστροσυκιά Ν. Πρεβέζης.” [Nomos Presbezês. Kastrosukia N. Presbezês.] Archaiologikon Deltion 24:253-254.

———. 1975. “Αρχαιότητες και μνημεία Ηπείρου. Νομός Θεσπρωτίας. Ανασκαφαί-τυχαία ευρήματα. Λαδοχώριον Ηγουμενίτσας.” [Archaiotêtes kai mnêmeia Êpeirou. Nomos Theprôtias. Anaskafai-tuxaia eurêmata, Ladoxôrios Êgoumenitsas.] Archaiologikon Deltion 30:211-213.

Wiseman, J. R. 2001. “Landscape Archeology in the Territory of Nikopolis.” In Ιsager 2001a:43-61.

Wiseman, J. R., and K. Zachos, eds. 2003. Landscape Archaeology in Southern Epirus, Greece. Hesperia suppl. 32.

Wiseman, J. R., K. Zachos, and Ph. Kefallonitou. 1992. “Συνεργατική Ελληνοαμερικανική Επιφανειακή Έρευνα στη Νότια Ήπειρο.” [Sunergatikê Ellênoamerikanikê Epifaneiakê Ereuna stê Notia Êpeiro.] Archaiologikon Deltion 47:293-298.

———. 1993. “Ελληνοαμερικανικό Διεπιστημονικό Πρόγραμμα Επιφανειακών Ερευνών στη Νότια Ήπειρο.” [Ellênoamerikaniko Deipistêmoniko Programma Epifaneiakôn Ereunôn stê Notia Êpeiro.] Archaiologikon Deltion 48:309-314.

Xenopoulos, S. 1993. Δοκίμιον ιστορικής τινός περιλήψεως της ποτέ αρχαίας και εγκρίτου Ηπειρωτικής Πόλεως και της ωσαύτως νεωτέρας Πόλεως Πρεβέζης [Dokimion istorikês tinos perilêpseôs tês pote archaias kai egkritou Êpeirôtikês Poleôs kai tês ôsautôs neôteras Poleôs Presbezês]. Orig. pub. 1884. Arta.

Zachos, K. 1993. “Καθαρισμοί–Στερεώσεις-Αποτυπώσεις μνημείων. Νομός Πρέβεζας. Θέση Φραγκοκλησιά κοινότητας Ριζών (αγροτεμάχιο Αφών Αθανασίου).” [Katharismoi-Stereôseis-Apotupôseis mnêmeiôn. Nomos Prebezas. Thesê Fragkoklêsia kionotêtas Rizôn (agrotemachio Afôn Athanisou).] Archaiologikon Deltion 48:301.

———, ed. 2007. Νικοπολις β’: Pρακτικά το Dευτέρου Διεθνούς Συμποσίου για τη Νικόπολη, 11-15 Σεπτεμβρίου 2002 [Nikopolis 2: Praktika to Deuterou Diethnous Symposiou gia tê Nikopolê, 11-15 Septembriou 2002]. Athens.

———. 2008. Άκτια. Αθλητικοί Αγώνες των Αυτοκρατορικών Χρόνων στη Νικόπολη της Ηπείρου [Aktia. Athlêtikoi Agônes tôn Autokratorikôn Chronôn stê Nikopolê tês Êpeirou]. Athens.

———. 2015. An Archaeological Guide to Nicopolis, Athens.

Zarmakoupi, M. 2020. “Harbors in the Sacral–Idyllic Landscapes of Early Roman Luxury Villas.” In Paesaggi Domestici. L’ Esperienza della Natura nelle Case e nelle Ville Romane. Pompei, Ercolano e l’ area Vesuviana, ed. A. Anguissola, M. Iadanza, and R. Olivito, 147–156. Atti del convegno (Pompei, 27–28 Aprile 2017).

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. I would like to warmly thank the Centre for Hellenic Studies for its support and help during the completion of this study. I would also like to thank Konstantinos Zachos and John Papadopoulos for their help and encouragement, as well as the personnel of the Ephorates of Antiquities of Igoumenitsa and Preveza, Ioannis Houliaras and Anthi Aggeli for supporting his research and for allowing access to all coastal sites. Finally I would like to thank my friends and colleagues Vyron Antoniadis and Andrea Babuin for their help with collecting and organizing the data for this study.

[ back ] 2. Livy 45.34.4-6; Plutarch, Life of Aemilius 29.

[ back ] 3. Franke 1961, 225-37; Sarikakis 1964, 107; Dakaris 1987, 14-7; Antoniadis 2016, 21.

[ back ] 4. Antoniadis 2016, 21-2.

[ back ] 5. Strabo 7.7.3.

[ back ] 6. Cicero, Letters to Atticus 5.16.1.

[ back ] 7. Isager 2007, 32.

[ back ] 8. Chrysos 1981, 38; 1997, 161; Cabanes 1997, 120; Zachos 2015, 34-5.

[ back ] 9. Sarikakis 1966, 213-4; Antoniadis 2016, 22.

[ back ] 10. Auboin 1959; 1965; IGRSS/IFP, 1966a-c; Besonen 1997, 6-11; Fouache 1999.

[ back ] 11. Pirazzoli 2005; Marriner & Morhange 2007, 146-51.

[ back ] 12. Besonen 1997, 11-13; Chabrol et al. 2012, 49.

[ back ] 13. Hammond 1967, 42, n.7; a 1-m sea-level rise since the Roman period has also been suggested for Butrintum by Ugolini (1935, 93).

[ back ] 14. Fouache 1999; Chabrol et al. 2012; 2022.

[ back ] 15. Tsoukalas 1911, 35-6; Vasilikou 2000, 615; Konstantaki 2015, 61-2.

[ back ] 16. Vasilikou 2000, 615; Vlachopoulou-Oikonomou 2003, 183; Riginos 2003, 292; Konstantaki 2015, 61.

[ back ] 17. Antoniadis 2016, Map 4.

[ back ] 18. Chabrol et al. 2022, 3.

[ back ] 19. Chabrol et al. 2022, Fig.6.

[ back ] 20. Tsoukalas 1911, 37.

[ back ] 21. Boetto 2016.

[ back ] 22. Chabrol et al. 2022, 3.

[ back ] 23. Tsoukalas 1911, 38.

[ back ] 24. A canal is regularly created on this ridge by dredging in order to allow large ferries travelling to and from Corfu and Italy to enter and leave the bay.

[ back ] 25. On the size draft of commercial vessels of the Hellenistic and Roman period see Nakas 2022, 17-30, Fig.2.1-2.2.

[ back ] 26. Beresford 2013, 31–3; King 1972, 96–8.

[ back ] 27. Riginos 1992, 347-8; Karatzeni 2001, 170; Antoniadis 2016, 70.

[ back ] 28. Hammond 1967, 80; Dakaris 1972, 204; Riginos 1999, 499-502; Riginos 2000, 656-7; Vasilikou 2000, 616-7; Karatzeni 2001, 170; Smiris 2004, 92-3;Labrou 2006, 266-7; Riginos 2007, 169-171; Vasileiadis et al. 2008, 98; Konstantaki 2015, 60; Antoniadis 2016, 66.

[ back ] 29. Preka-Alexandri 1995, 445-6; Riginos 1999, 495; Vlachopoulou-Oikonomou 2003, 156-7; Akrivopoulou & Lazari 2005; Riginos 2005, 568; Labrou 2006, 265-6; Lazari & Lazou 2007; Riginos 2007, 168-9; Vasileiadis et al. 2008, 98; Kanta-Kitsiou et al. 2008, 38-9; Kanta-Kitsiou 2009, 15; Konstantaki 2015, 52-7; Antoniadis 2016, 67-9.

[ back ] 30. Riginos 1999, 494-7; 2007, 169; Akrivopoulou & Lazari 2005, 413; Konstantaki 2015, 54.

[ back ] 31. Vokotopoulou 1975; Αgalopoulou 1975; Vlachopoulou-Oikonomou 2003, 156-7; Bowden 2003, 63; Riginos 2007, 169; Labrou 2006, 264; Kanta-Kitsiou 2009, 15; Antoniadis 2016, 69.

[ back ] 32. Hammond 1967, 79; Dakaris 1972, 145-67; Karatzeni 2001, 170; Riginos 2007, 165; Lazari et al. 2008, 23; Konstantaki 2015, 66; Antoniadis 2016, 65.

[ back ] 33. Dakaris 1972, 145-6.

[ back ] 34. Tsoukalas 1911, 40-1.

[ back ] 35. Dakaris 1972, 100, 136, 200; Karatzeni 2001, 169; Andreou 1979, 246, n.22; Antoniadis 2016, 61-2.

[ back ] 36. Hammond 1967, 77; Dakaris 1972, 15, 136; Konstantaki 2015, 67.

[ back ] 37. Dakaris 1972, 200.

[ back ] 38. Plutarch, Life of Antony 63.2.

[ back ] 39. On the size of Hellenistic and Roman warships see Morrison & Coates 1996, Appendix D; Nakas 2022, 27-8, Table 2.4.

[ back ] 40. Cassius Dio, 50.12.2.

[ back ] 41. Besonen 1997, 49-51, Fig.16; Besonen et al. 2003, Fig.6.13.

[ back ] 42. Morrison & Coates 1996, Appendix D.

[ back ] 43. Chrysostomou 1980, 320-3; 1982, 10-21; Zachos 1993, 301; Angeli & Katsadima 2001, 91-4; Konstantaki 2015, 80-1; 2018, 30; Antoniadis 2016, 31.

[ back ] 44. Vokotopoulou 1969, 253-4; Dakaris 1972, 95; Chrysostomou 1980, 320-1; Angeli & Katsadima 2001, 94-100; Karatzeni 2001, 169; Moore 2001, 79; Flämig 2007, 144-5; Stefanidou-Tiveriou & Papagianni 2014, 245-8, 258-52; Stefanidou-Tiveriou 2014, 511-24; Konstantaki 2015, 81-4; 2018, 30; Antoniadis 2016, 32.

[ back ] 45. Bruneau 1981, 116–8; Ugolini 2020; Zarmakoupi 2020.

[ back ] 46. Isager 2001b.

[ back ] 47. Strabo 7.7.5.

[ back ] 48. Tsoukalas 1911, 44-5; Hammond 1967, 47; Dakaris 1972, 95; Antoniadis 2016, 31.

[ back ] 49. Zachos 2015, 90, 107-10; Antoniadis 2016, 35, 38.

[ back ] 50. Jing & Rapp 2003, 164-73, Fig. 5.10; Antoniadis 2016, 33.

[ back ] 51. Antoniadis 2016, 45-6 with further and updated bibliography on the various monuments of the area.

[ back ] 52. Zachos 2008, 48; 2015, 84-5.

[ back ] 53. Strabo 7.7.5.

[ back ] 54. Kotsovilis 1898, 134; Tsoukalas 1911, 52.

[ back ] 55. Jing & Rapp 2003, 174-7.

[ back ] 56. Hammond 1967, 48; Wiseman et al. 1993, 310; Karatzeni 2001, 168; Stein 2001, 70; Jing & Rapp 2003, 162-4, 174-7; Riginos 2012, 355; Konstantaki 2015, 115-6; 2018, 29; Antoniadis 2016, 49.

[ back ] 57. Konstantaki 2015, 115-6.

[ back ] 58. Tsoukalas 1911, 52.

[ back ] 59. Jing & Rapp 2003, 179-98.

[ back ] 60. Hammond 1967, 57-61; Dakaris 1971, 177-9; Karras 1997; Karatzeni 2001, 169; 2011, 148-9, 153; Moore 2001, 79; Jing & Rapp 2003, 179-92; Antoniadis 2016, 29.

[ back ] 61. Xenopoulos 1993 (1884), 44-5; Petsas 1950-51, 40-1; Hammond 1967, 61; Dakaris 1971, 59, 95; Papadopoulou 1989, 285; Wiseman et al. 1992, 295; Zachos 1993, 303; Douzougli 1993, 282; 1994, 382-3; 1998, 75; Chiotis 1998; Karatzeni 2001, 168; Moore 2001, 79; Wiseman 2001, 46-7; Jing & Rapp 2003, 194-7; Bowden 2003, 386-7; Konstantaki 2015, 90-4; 2018, 32; Antoniadis 2016, 48.

[ back ] 62. Strabo 5.3.5; Dionysius of Halicarnassus 3.44.3. Cf. Nakas 2022, 32-3.

[ back ] 63. Delano Smith 1979, 327–8; Leidwanger 2013; 2020, 152–66.