Citation with persistent identifier: Kalliontzis, Yannis. “The Shrine of the Valley of the Muses: An Archaeological, Historical and Literary Revisited.” CHS Research Bulletin 8 (2020). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:KalliontzisY.The_Shrine_of_the_Valley_of_the_Muses.2020

Sometimes the biggest discoveries in ancient studies are hiding in places that are already considered fully excavated. The study of old material kept in chaotic storerooms is sometimes very rewarding. One excellent example of this phenomenon is the sanctuary of the Muses in the Valley of the Muses in Ascra in Boiotia in Central Greece near the great mountain of Helicon.

This sanctuary acquired a particular fame during antiquity. This fame was based on the works of the great epic poet Hesiod. Hesiod lived in the small city of Ascra near Helicon and the Valley of the Muses and was, according to his own testimony in the Theogony, a shepherd who was inspired by the Muses in the Helicon and who began to produce his magnificent poetry.

The fame of Hesiod contributed to the creation of an important sanctuary of the Muses at Helicon that attracted pilgrims from all the Greek world. The festival of the Mouseia in honor of the Muses and of the Erotideia in honor of Eros became important. It is not easy to say when the contest of the Mouseia was established since we have some allusions that a contest already existed in the 4th century. But the Mouseia attracted participants from all over the Greek world. The Mouseia were mainly poetical and musical contests that were celebrated in the theater of the sanctuary. The sanctuary continued to be important during late antiquity, but in the fourth century the progress of Christianization limited its importance. In a characteristic move, the emperor Constantine took a group of bronze statues of the Muses to Constantinople in order to decorate his new capital. And as we will see, an early Christian church was built upon the ruins of the altar of the Muses.

The sanctuary was forgotten during the medieval period and its region was partly abandoned. But the mentions of the sanctuary in classical writers attracted many European travelers already in the 18th century. After many attempts, the position of the sanctuary was securely established at the middle of the 19th century by Greek, German and French travelers and archaeologists. They found that many inscriptions mentioning the muses were built into the small church of Agia Trias, in the Valley of the Muses. The first excavations that confirmed the exact position were conducted in 1870s. But the first systematic excavations began at the end of the 19th century by the French School at Athens. Paul Jamot, who was then a young member of the French School, excavated in the Valley for many months during the period from 1888 to 1890.

He found many inscriptions and statue bases built into the churches. Jamot had sometimes around 50 workers who were digging all around the Valley trying to find something interesting. He presented vividly his discoveries in the Valley in a small autobiographical book, En Grèce avec Charalambos Eugenidis, that was published in Paris in 1914.

Jamot made important discoveries in the Valley; he discovered the monumental altar of the Muses, six by ten meters, and many statue bases and architectural blocks lying around this monument. About 40 meters west of the altar he discovered an Ionic stoa, running roughly north-south. This very large stoa — more than 300 feet long and 30 feet deep — was poorly preserved. The discovery of ionic capitals proves that the stoa had an ionic decoration. From the drone photo you can see that this stoa is nowadays nearly invisible. The northern part of the stoa is better preserved.

300 meters to west of the stoa he discovered the theater of the sanctuary making use of the natural slope of the Helicon. Jamot excavated the stone skene and proskenion of the theater, that was rather badly preserved. It seems that the theater never had stone sits, but it was a big theater capable of accommodating the pilgrims who came to the sanctuary during the festivals.

During his excavations Jamot found a lot of statue bases, inscriptions and fragments of sculptures. He most notably found fragments of bronze sculptures. Jamot didn’t limit his research to the Valley of the Muses; he excavated also in the city of Thespiai that controlled the sanctuary from the Hellenistic period and onwards. In this excavation he found the statue of the Muse. The material from the excavations of Jamot was dispersed in different museums.

From the excavations of Jamot, it was clear that the sanctuary was particularly important during the Hellenistic and Imperial period. Most of the buildings seem to belong to the second half of the third century. During the Hellenistic period the sanctuary attracted the donations of many Hellenistic rulers and especially of the Ptolemies, who because of the creation of the Museum of Alexandreia were particularly interested about the most famous Museum of the Greek world.

Jamot published most of the inscriptions that he found in his excavations and some of the sculptures. Many factors influenced this aspect of the French excavations in the Valley. First of all, the first half of the 20th century was a very difficult for Greece and Europe with nearly continuous war and disruptions.

But, the sanctuary of the Muses was not forgotten. The inscriptions, especially the epigrams attracted a lot of scholarly interest and were studied but important historians and epigraphists. Archaeologists also came back to the Valley after the second world war but by that time the sanctuary was already covered with soil from the nearby mountains and most of the monuments were invisible. The French archaeologist George Roux visited the site in 1950s and produced the first plan of the sanctuary based on the archives of Jamot and his autopsies. Many years later, in the 1980s a British team led by A. Snodgrass and J. Bintliff organized a survey in the Valley with many interesting results about the history of the landscape but once again the monuments were invisible. R. Höschele has recently written an excellent article about the epigrams from this site.

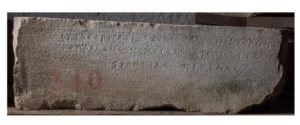

My own interest on the Valley was provoked also by poetic inspiration. When I was working as a curator in the Museum of Thebes, I noticed an important base from the sanctuary in rather bad condition that was stored in the museum. It was a big base bearing the bronze statues of the nine muses. The blocks of this base were found built in the demolished church of Agia Trias. Each base bore also the name of each muse and an epigram about the Muse that was signed by the poet Honestus. Honestus was a Corinthian poet of the age of Augustus that is also known from the Palatine Anthology.

These epigrams were published by Jamot and studied by great philologists but we had never previously studied the traces of bronze statues on top of the base. So, with my colleague from the French School Prof. Guillaume Biard, we decided to join our forces in order to study both the epigraphical and the archaeological aspect of the monument. What we found is that the epigrams composed by Honestus were ekphrastic: they described the bronze statues of the Muses.

Honestus created a poetic anthology on stone in the shrine of the Muses by inscribing epigrams on monuments that were sometimes already centuries old. In a truly exceptional way, he signed the epigrams that he inscribed on the monuments like no other poet did. He wasn’t very shy about his art. And it is one of the rare cases of poets known from the philological tradition whose poems are also preserved on stone.

Honestus wasn’t the only poet signing epigrams in the sanctuary of the Muses. Inscribed in a base was found this epigram signed by a poetess Herennia Procula.

This Eros teaches desire. Aphrodite herself said,

“Where did Praxiteles see you with me?”

By Herennia Procula.

This also some kind of ekphrastic epigram since it was linked to the famous statue of Eros made by the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and dedicated to the sanctuary. This is also an exceptional epigram because is one of the rare epigrams that are signed by a poetess.

The study of these important inscribed monuments from the sanctuary of the Muses led us to reexamine the archaeology of the sanctuary and to realize how little has been done for many decades. We thought that it was urgent to prepare the final publication of the results of the excavations of Paul Jamot. In the archives of the French School at Athens we found a report prepared by Paul Jamot and one of his collaborators in the excavation André de Ridder that gives us new information about his excavations and could help us better understand the mess that he created.

As a priority we set the study of the altar of the Muses which was the central monument of the sanctuary. For two excavation periods in 2018 and 2019 we excavated the altar of the Muses in order to arrive at the level that Jamot has left. This excavation was undertaken in collaboration with the Ephorate of Antiquities of Boiotia under Dr. Alexandra Charami and was financed by the French School at Athens and the French endowment “Archéologie et patrimoine en Méditérannée”.

The excavation of the altar permitted us to find a lot of new elements about the history of the monument. It is not only the initial phase of the monument that is interesting. Thanks to the new excavations we discovered a new phase in the history of the monument. A wall that was built at the west side of the altar was part of an early Christian church that was built on the altar. This church was built with reused material from the altar and the honorific monuments that stood around it. The proof for the existence of this Christian monument was the discovery of reused blocks from ancient monuments where crosses were carved. It was of course a common phenomenon for early Christian churches to be built on ancient temples and sanctuaries. The presence of this early Christian church might have been the cause of the great destruction and the transfer of the honorific monuments that stood around the altar of the Muses. A lot of the honorific bases and other architectural blocks were piled at the northern and eastern part of the terrace of the altar. It is possible that all these blocks were piled there during the early Christian period. We tried to clean these piles and found many blocks belonging to the altar and other blocks belonging to honorific monuments. The new excavations brought to light new elements about the architecture of the altar. But we rediscovered only a small part of the blocks excavated by Paul Jamot and a lot remain to be found if we continue our research.

We found the blocks that belonged to the first course of the entrance of the monument at the west. Some of the blocks of the first course of the entrance preserved the lifting bosses. We also identified many blocks that have been rebuilt in the early Christian church and belong to the altar. Two blocks from the first course of the entrance of the monument were built in the northern wall of the early Christian church. The traces of clamps and pry marks in the upper surface of the second course of the upper structure of the altar help us to place accurately the scattered blocks belonging to the altar.

Two courses of the upper part of the altar are preserved. The first course that is based on the foundation layer of the altar is decorated with one recessed band and the second course has two recessed bands. On the second course of the altar were based large orthostates that were part of the sacrificial table, the prothysis. We identified two of these large orthostates in the pile of stone at the northern part of the terrace of the altar.

Of course, many more blocks remain to be found in the vicinity of the altar that could complete the plan of the monument, but for now we have a stable base for the study of the monument. The great number of blocks that belong to the altar could make possible a restoration of this important monument in the future. From what we understand from the study of the architecture of the altar till now, this monument could date to the second half of the third century or later. This period was one of the best moments for the history of the sanctuary and Boiotia in general.

Much remains to be done for the study of the shrine of Muses. In collaboration with Prof. Guillaume Biard we are now preparing the publication of a new study of the altar of the Muses that would be combined with a publication of the archives of Paul Jamot. This study will be published by the French School at Athens.

Fortunately, or unfortunately the Valley of the Muses is a site off the beaten path of tourists in Greece. This is why it has kept its natural beauty and tranquility. But, it will be helpful to attract more knowledgeable people to this important site without disturbing the natural environment.

The CHS fellowship permitted me, thanks notably to the very rich library of the Center and its online resources, to gather all the literary and epigraphical testimonia on the sanctuary of the Muses and to treat the data from the recent excavations on the site. My work at CHS will form the basis for the preparation of the final publication of the altar of the Muses that will be edited by the French School at Athens.

Select Bibliography

Biard, G., Y. Kalliontzis, and A. Charami. 2017. “La base des Muses au sanctuaire de l’Hélicon.” BCH 141:697-752.

Bintliff, J. 1996. “The archaeological survey of the Valley of the Muses and its significance for Boeotian History.”

Bintliff, J., and A. Sondgrass. 1985. “The Cambridge/Bradford Boeotian Expedition: The First Four Years.” Journal of Field Archaeology 12:123-161.

Gutzwiller, K. 2004. “Gender and Inscribed Epigram: Herennia Procula and the Thespian Eros.” TAPhA 134:383-418.

Höschele, R. 2014. “Honestus’ Heliconian Flowers: Epigrammatic Offerings to the Muses at Thespiai.” In Hellenistic Poetry in Context, ed. M. A. Harder, R. F. Regtuit, and G. C. Wakker, Hellenistica Groningana 20:171-194.

Jamot, P. 1902. “Fouilles de Thespies (suite). Le monument des Muses dans le bois de l’Hélicon, et le poète Honestus.” BCH 26:129-160.

———. 1914. En Grèce avec Charalambos Eugenidis. Paris.

Müller, Chr. 1996. “Les recherches françaises à Thespies et au Val des Muses.” In La Montagne des Muses, ed. A. Hurst and A. Schachter, 171-183.

Robinson, B. 2012. “The Production of a Sacred Space: Mount Helikon and the Valley of the Muses.” JRS 25:227-258.

Roesch, P. (2009)2. Les inscriptions de Thespies. Ed. G. Argoud, A. Schachter, and G. Vottéro 2007-2009. Lyon. (http://www.hisoma.mom.fr/thespies.html) = I.Thespies.

Roux, G. 1954. Le Val des Muses et les Muses chez les auteurs anciens », BCH 78:22-48.

Schachter, A. 1981–1994. Cults of Boiotia, 4 vols. = BICS Supplement 38. London.

———. 1996. “Reconstructing Thespiai.” In La Montagne des Muses, ed. A. Hurst and A. Schachter, 99–126. Geneva.