This week I have been looking at representations of klinai (couches) on Greek vases . . . lots of klinai on lots of Greek vases, thanks to the miraculous Beazley Archive Pottery Database. I am intrigued by the variety of ways Greek vase-painters depicted the couches on which their symposiasts recline, couples embrace, heroes brood, or dead lie in state. Some of this variety is surely due to changes in furniture fashion (such as the emergence of fulcra, or curved headrests, in the second half of the fifth century), and we know that several different couch types co-existed through the sixth and fifth centuries BCE, from both visual and epigraphic evidence (the Parthenon inventories distinguish two types of klinai, “Chian-made” and “Milesian-made”). But what did it mean when a painter juxtaposed three different couch types on a single cup?

The Foundry Painter did so, on a red-figured cup in Cambridge, ca. 480 BCE (Beazley Archive vase number 204353). One side of the cup shows two pairs of bearded symposiasts reclining on two couches with raised backs, like ‘chaises longues,’ and being entertained by a nude aulistes while one of them sings along. The other side shows four bearded men arranged on three klinai with volute capitals, but with the rightmost couch depicted from the side, to suggest the L-shaped arrangement of couches in the space of a real andron; these men are somewhat more reserved, though they are all clearly drinking or have already had too much. The interior tondo features yet another couch type, with plain, rounded capital (a pared-down version of the archaic ‘Type B’ variety with volute capital); its occupant is balding and plays the aulos himself, while a boy dances. All the scenes are equally sympotic, and looking carefully at other details (presence or absence of tables, women, etc.) does not help us decode the significance of this variation. Perhaps it is a form of the ‘repetition with variation’ that characterizes the work of one of the masters of Attic black-figure, Exekias, and his red-figure legacy. The variation is striking when compared to another cup attributed to the same painter, Boston 01.8034 (Beazley Archive vase number 204352), where the symposiasts of all three pictorial zones occupy the same kind of couch (the lounge-chair type). So, on the Cambridge cup, was the Foundry Painter simply experimenting with depicting different types of furniture, or showing off his skill? Was he presenting something for every possible user to identify with, as Osborne implies when he discusses this vase as a model for “Projecting identities in the Greek symposion” (in Material Identities, ed. J. Sofaer, 2007)? Or did the type of couch on which one reclined at early fifth-century symposia carry some meaning, so that there is a juxtaposition here of different modes of sympotic activity? Was the interior scene meant to appear more homely or common, perhaps? It shows the simplest of the three couch types, one that is especially common in fifth-century vase-painting and is a favorite of Makron, one of the Foundry Painter’s contemporaries.

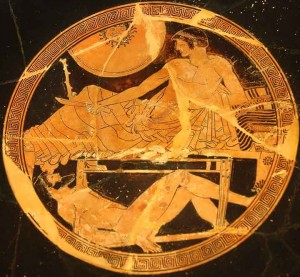

With Makron, we find more consistency of couch type. I am still in the process of tracking down images for all of the seventy-odd vases attributed to Makron with scenes of symposia or featuring klinai in other contexts, but a preliminary survey suggests that in the overwhelming majority of his symposium scenes involving couches, the revelers recline on couches like that on the interior of the Cambridge cup, with plain legs and plain, rounded capital. There are a few exceptions, however, with the lounge-chair type, or with another type with turned legs and curved armrest, favored by Douris, or with the full ‘Type B’ scheme. Only three examples with ornate, Type B klinai are known among Makron’s works, and the one that is best preserved shows Achilles reclining over the body of Hektor, with knife in hand to signal feasting though his table is empty (Louvre G153, Beazley Archive vase number 204695):

The other two examples also come from cup tondoes but are so fragmentary that we cannot be sure of their narrative context, but it is interesting to speculate (and isn’t that what the blogs are for?): Did Makron reserve the ornate Type B kline for heroic contexts, because of its luxurious and archaizing appearance? Can we assume that the other tondoes with such klinai also depicted the Ransom of Hektor, or some other mythical ‘symposium’? Well, no. For one thing, it’s never safe to make interpretive assumptions about vase paintings, which never cease to surprise us, and if we were to make an assumption here, it could just as easily go the other way: it is unlikely that Makron put a Ransom of Hektor on the interior of a cup with a courtship scene on the exterior, as is clearly the case for one of the fragmentary examples (the other preserves only a single foot on the exterior). Although Makron did evidently like to juxtapose different themes on his cups (such as courtship of hetairai and women working wool, or courtship of women and courtship of boys), there is usually some relation between themes that makes some kind of statement—a form of narrative—and on the Louvre cup Hektor’s ransom is paired with the sacrifice of Polyxena, which takes place over both exterior zones. So it is safest to identify the fragmentary scenes simply as ‘symposia,’ as Beazley did.

Still, would representing a symposiast on such a luxurious and old-fashioned couch assimilate him, in some way, with a mythical hero like Achilles? How common were Type B klinai in real usage in the fifth century? Physical evidence for such inlaid klinai is limited to sixth-century funerary contexts. They are listed in fifth-century sanctuary inventories and replicated in stone in monumental tombs of dynastic cultures in Asia Minor (and in Macedonia), but neither of these contexts give any indication of the normalcy of such klinai at Classical symposia.

These are the kinds of questions and issues that I am exploring as I wade through the sea of kline-images in Greek vase painting. While I search for comparanda for details on funerary klinai of other media and try to clarify the stylistic development of kline types, I am finding much fuel for thinking about larger questions, like what meaning(s) Type B klinai may have carried in the fifth century.