Citation with persistent identifier:

Galanakis, Yannis. “On Her Majesty’s Service: C. L. W. Merlin and the Sourcing of Greek Antiquities for the British Museum.” CHS Research Bulletin 1, no. 1 (2012). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:GalanakisY.On_Her_Majestys_Service.2012

The Diplomatic Pouch

§1 The collection and trafficking of antiquities and art objects through the intervention of diplomatic services is neither new nor revelatory.[1] With regard to Greek antiquities, this subject has already been discussed either in relation to the actions of individual ambassadors and consuls or, as in the excellent recent monograph by Patrizio Gunning,[2] the operation of particular services in specific regions and periods. The names of Choiseul-Gouffier, Fauvel, Elgin, Strangford, Gropius, Prokesch von Osten, Faber, Photiades Bey, Newton, Biliotti and Saburov, among several others, highlight the long-standing interest of diplomats in sourcing and trafficking antiquities from Greece. One may then ask, why is another paper on the subject needed?

§2 Perhaps surprisingly most of these studies focus either on periods before the independence of Greece or on areas, such as Asia Minor and the Dodecanese, which were outside the newly-founded kingdom’s remit during the 19th century.[3] If we want to identify the protagonists involved in the trafficking of antiquities in modern Greece, in the period of the first antiquities law (1834-1899), and to reconstruct the structure and organization of their operations – as this research is aiming to achieve – then we have to turn our attention to the diplomatic services stationed in Greece itself. Their dispatches offer a rich, and hitherto underexplored, material of research.

§3 My current project on “Tomb Robbers, Art Dealers and the Trafficking of Antiquities” is based largely on British material.[4] So far I have been able to reconstruct the operation of the major Greek collectors and dealers, such as Professor Athanasios Rhousopoulos[5] and the Lambros family (the eminent numismatist, Pavlos Lambros, and his son Jean), and to identify the numerous secondary dealers and private diggers involved in the trafficking of antiquities,[6] especially in the period between 1860 and 1900 which is undoubtedly better documented in the archival sources.

§4 With the present paper, I make a first attempt to introduce one of the “foreigners” in the antiquities trafficking story – namely antiquarians, agents, or diplomats, who either went to or resided in Greece with the purpose of combining work with leisure that is commercial and academic pursuits with the acquisition of antiquities. Here I offer a preliminary biographical account of Charles Merlin – an agent of Her Majesty’s government stationed in Greece for half a century (1839-1887). His lively manuscript dispatches to the British Museum (hereafter BM) contain a wealth of information with regard to the trafficking of antiquities.

A Trading Consul in the Piraeus

My position is exactly the same as that of my other colleagues, no advantage whatever is obtained by a Trading Consul in consequence of his official position, beyond a certain kind of security his house may be considered to enjoy during a Revolution. That the latter is the case I have ascertained from personal experience, when I was British vice-consul at Athens…after the expulsion of King Otho from Greece.[7]

§5 Charles Louis William Merlin was born in 1821 (Figure 1).[8] The son of Augusta and François-Nicolas (Francis Nicholas), Charles was apparently related from his father’s side to French nobility – the family of Merlin de Douai, fervent supporters of the French revolution, many members of which sought refuge in adjacent countries following the restitution of monarchy in France in 1814. This story may perhaps explain how Charles’ father reached England,[9] though I have not so far been able to trace him or his mother in the records of the National Archives.

Source: To Asty, vol. 2, issue 78, 15 March 1887, p. 4; signature adapted by the author from Merlin’s correspondence with the British Museum.

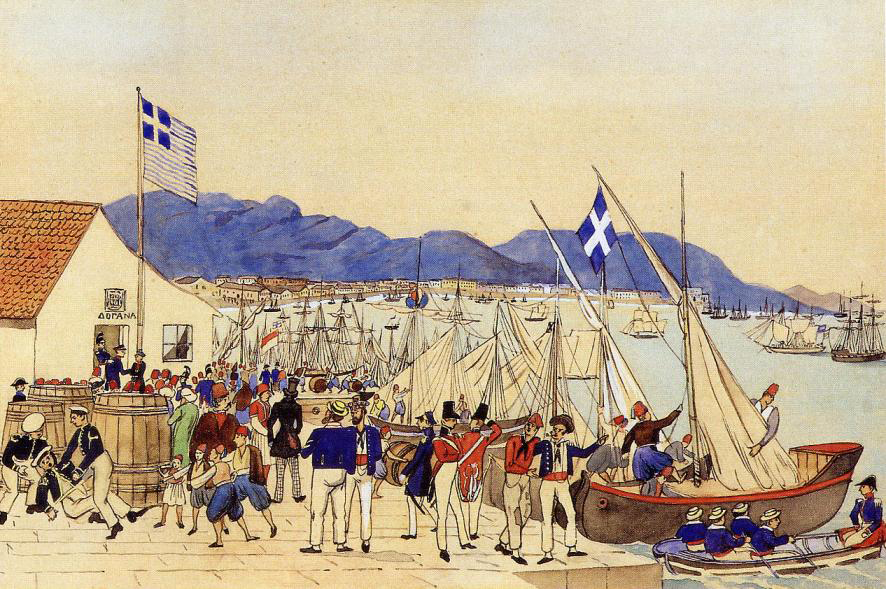

§6 Very little is known about Charles’ childhood in London, other than that he is said to have received “a good education”.[10] Fluent in French and English, Charles was appointed in 1839, at the age of 18, chancellièr (clerk) to the British consulate of continental Greece at the Piraeus, at a time when qualifications for the post included, other than language skills, good penmanship and a willingness to represent British trade interests abroad.[11] When he moved to Athens the city had just become the capital of the newly founded kingdom and had a population of about 5,000 people (with the Piraeus having a population of 1,000 people: Figure 2) – in that sense, Charles became, among numerous other foreigners (most forming part of King Otto’s entourage), one of the first “oecists” of modern Athens.

Source: National Historical Museum Greece.

§7 Seven years after his arrival in Greece, on 6 April 1846, he was appointed unpaid vice-consul of the Piraeus and agent of the Ionian Bank – a British overseas institution established in 1839 in the Ionian Islands (a British protectorate until the islands’ annexation to Greece in 1864).[12] The status of an “unpaid” vice-consul allowed young Charles, as many of his fellow consuls, to maintain his commercial advantages and right to trade – a situation largely inherited from the Levant Company, a commercial enterprise and, in a way, the precursor of the British Consular service in the East Mediterranean.[13] Although some individuals profited from this situation, others could not afford an appropriate life and had very little in terms of an alternative form of income.[14] Moreover, the British press started progressively to criticize the status of these “mercantile consuls” by pointing out that it endangered the government’s interests in the region not least because most of these consuls-merchants often put their interests before that of the British government in their pursuit of making money (i.e., even turning, in some instances, into “rogue” consuls[15]). In addition, most of these trading consuls, as purported by The Times, often ignored or sidelined their political and judicial functions.[16] It was only from the 1860s that a fixed salary enabled the personnel of the consular service to live independently of their commercial profits. In short: before Merlin started receiving a government salary (in the 1860s), he had to rely on his commercial skills and business proceeds rather than on his involvement in the consular service.

§8 On 31 August 1847, Charles married Isabella Dorothea Green (1822-1902) in London. Isabella was the eldest daughter of the Scot merchant Philip James Green, who had served as the British consul for the Morea during the Greek war of independence (based at the time with his family at Patras).[17] A branch of the Green family set up the first, and for a long time the only, British mercantile house in Greece (also based at Patras), the John Green and Co., in which young Merlin was apparently a partner.[18] Isabella and Charles had six children, only three of whom survived the age of two:[19] Charles Edward Prior (1850-1898),[20] Sidney Louis Walter (1856-1952)[21] and Augustus Alfred Cornwallis Eliot (1860-1948).[22]

Source: http://archives.getty.edu:30008/getty_images/digitalresources/gary_edwards/jpegs/grl_92r84_04-23-01.jpg

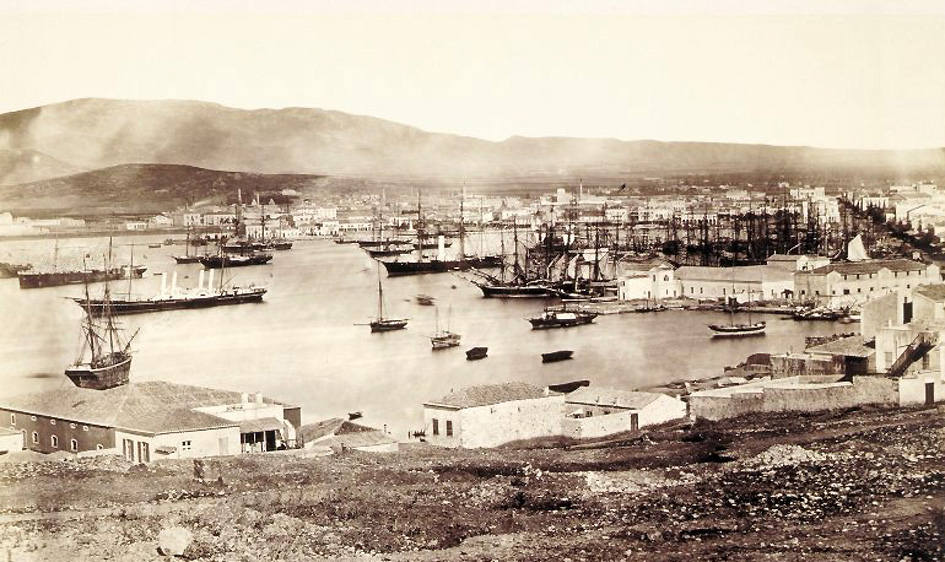

§9 In 1854 Charles was appointed vice-consul of the districts of Attica, Boeotia and Northern Greece (i.e., to the Spercheios Valley and the borders with the Ottoman Empire) and moved temporarily from the Piraeus to Athens. In 1865 he was promoted to Inspector General (Manager) of the Athens branch of the Ionian Bank, the head office of which moved from Corfu to Athens in 1873. In 1868 the Merlins moved back to the Piraeus[23] following Charles’ promotion to the consulship in Her Britannic Majesty’s government (Figure 3).

§10 From 1868 until his retirement from the consular service in 1887, Charles received an annual salary of £350 and an additional sum of £100 for office expenses (i.e., a total of £450 or ca. 12000 drachmas p.a.).[24] Under his direction he had a clerk (paid annually £85 from the office expenses) responsible for attending to as much business as he could transact, registering documents, copying and docketing returns and dispatches and keeping the registers and archives in proper order – in short, for keeping the consulate running. Charles’ salary was the second worst among the high-ranking British consuls in Greece, better only to the consul at Missolonghi who earned £200 p.a. For example, the consul at Patras earned £700 p.a., while the consul-general at Constantinople received £1,600. The relatively small salary appears to reflect, in this instance, the limited activity of the Piraeus consulate and consequently the consul’s restricted responsibilities.

§11 Piraeus was until the 1870s a small port principally used to supply the consumption of the capital. Syros, Patras and Corfu remained, for most of the 19th century, Greece’s main commercial hubs. Based on Merlin’s own reports, submitted to the House of Commons, only 756 ships entered the Piraeus (252.706tn) in 1868. By 1885, the situation had changed dramatically with the port witnessing an increase of 1100% in the total number of ships entering (8.934) and of 950% in terms of tonnage carried to the Piraeus (2.395.386tn).[25] The population had equally multiplied over the years and in the 1880s some 20,000 people lived around the port.

§12 With Her Britannic Majesty having an Envoy Extraordinary at Athens, the British consulate at the Piraeus “must be considered strictly a commercial one”[26] – and Merlin, despite the changes in the British consular service mentioned above, retained his permission to trade “in virtue of which holds the post of General Manager of the Ionian Bank, but by that appointment is precluded from engaging in commercial business of his own account.”[27] His consular salary combined with that received from the Ionian Bank, as Inspector General of the Athens Branch (around £600 p.a.), yielded annually around £950-1,000 – not a huge amount by British standards of the time, but certainly a substantial amount by the standards of Athenian society and Greece as a whole (i.e., 25000-26000 drachmas, when a full-time professor at the university of Athens earned annually around 4000 drachmas and the vice-director of the Bank of Greece around 8000 drachmas). The extra perk of his affiliation with the Ionian Bank was that his house rent, firing and lighting, were all paid for him by the Bank, thus securing to him and his family a very comfortable life in Athens, at least between the 1860s and 1880s. His investments in land and property around continental Greece and the islands appear to reflect his increasing wealth, especially from the 1860s onwards.

§13 In the summer of 1887, and after 49 years of involvement in the British consular service and of commercial pursuits in Greece, he retired at the age of 67 and moved with his wife from Athens to London.[28] Between 1887 and 1891 he served as the Ionian Bank’s General Manager in London frequently travelling to Greece in order to inspect the various branches and their operation. Upon his retirement at the end of 1891 he was invited to join the Bank’s Court of Directors with a pension of £400 and an additional fixed fee of £200 annually for his position in the Court.[29] He lived at Campden Hill, near Kensington in west London, and remained as one of the Bank’s Directors until his death on 23 August 1896 at the age of 75. The Bank’s Court decided to continue his pension to his widow until the end of 1896 “as a mark of appreciation of the very valuable services rendered by Mr Merlin…for so many years”.[30] His wealth at death (all of which went to his wife) was £3,695 9s.[31]

§14 Merlin appears to have had a successful diplomatic career,[32] depending also on how one wants to read the fact that for 50 years he did not receive another diplomatic posting – a situation reflecting well the immobility of British consuls who, unlike their French or Russian counterparts, could remain in one place their entire working life, “if no urgent political, or other, matter led to a change in their appointment”.[33] His duties included commercial business (dispatches, letters, returns), observing the exports and imports at the Piraeus and the traffic of commercial and war ships, the issuing of visas and bills of health, attestations of signature, resolving protests and disputes among masters of British merchants’ ships and their crews and listening to the complaints of British subjects (“the Ionians” – until 1864 – and the Maltese).[34] Generally, however, it appears that outside the consul’s commercial duties, there was a certain amount of flexibility as to what he should or was expected to do – a flexibility also originating from the situation on the ground. And from the extent of his correspondence with the BM and his full-time work in the Ionian Bank, it appears that his diplomatic duties (and the efficiency of his clerk at the consulate) left him with considerable spare time at his disposal. In this respect, Charles’ business acuity as a financier and land investor, his command of Greek and fluency in French, his integration in the upper echelons of Athenian society and the support he showed towards Greek affairs afforded him with great respect within the kingdom and its authorities.[35]

§15 It is from the 1850s that Merlin appears to be more actively engaged in diplomatic actions. His knowledge of the country and its people made him an invaluable source on the ground. He participated in mixed commissions, such as those dealing with the revolts in Epirus and Thessaly in 1854 and 1878, and in crime investigations, especially those relating to the murders of British citizens in Greece (e.g., the murder in 1856 of Mr and Mrs Leeves and their newborn child by brigands in Euboea and the 1882 investigation regarding the death of Charles Chaloner Ogle, correspondent of The Times, at Pelion during the 1878 revolt). In the tumultuous period that followed the expulsion of King Otto from Greece (late 1862–early 1863), he provided assistance to many Greeks and in addition took under his protection the Bank of Greece (an action entrusted to him by the Bank’s Director). He was also responsible for securing a number of loans for the Greek government through the mediation of the Ionian Bank. In Greece he left an excellent reputation and an illustrious family.

“Believe me Sir, I remain, Yours Faithfully”

§16 Merlin never rose to the caliber of diplomacy of Sir Alfred Biliotti with whom he shared the passion for sourcing antiquities for the BM.[36] It is as a financier, merchant and investor that Merlin is mostly remembered and this is also reflected in his dealings with the BM.

§17 The BM today houses around 450 Greek antiquities, some of outstanding quality and importance, that were purchased from Charles Merlin over a period of 30 years (1865-1892).[37] Most of them comprise objects of classical antiquity, though earlier and later periods are also represented, as do several artifactual categories ranging from dolls and figurines (Figures 4, 9), bronzes (Figures 5, 6) and vases (Figures 7, 8, 10) to stone tools, coins, gems, and a few forgeries.[38] Although Merlin was a subscribing member of the Athens Archaeological Society (1860-1880), and would occasionally donate a few objects to the Society’s Museum and to the Numismatic Museum in Athens, he most frequently purchased objects from Athenian collectors and dealers with a clear purpose of either forwarding them to the BM or selling them to other interested parties.

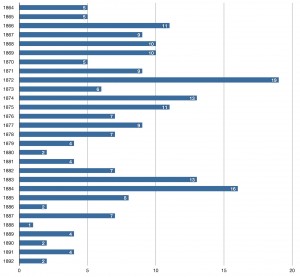

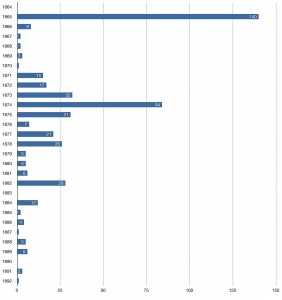

§18 In order to reconstruct Merlin’s dealings with the BM I decided to go back to the original material – his manuscript dispatches. They form a substantial body of evidence comprising, at least, 212 letters (Table 1) or more than 650 pages (ca. 50,000 words of transcribed text). The correspondence I have been able to examine covers a period of 29 years (1864–1892) offering very important insights, especially with regard to the value of objects and the structure of his transactions with the BM.[39] To this material one should also add the 52 reply letters (written between 1868 and 1886), copies of which are still kept in the archives of the department of Greek and Roman antiquities at the BM.

§19 Although other consuls from within the kingdom of Greece were in correspondence at the same time with the BM (e.g., from Patras, Syra, Corfu, and after the annexation of Thessaly, from Volos), Merlin’s letters constitute the largest single body of evidence for the sourcing and trafficking of antiquities from Athens to London between the 1860s and 1880s, even when the letters of all the other consuls stationed in Greece and of all the Greek collectors and dealers sent to the BM during the same period are combined together. Most of the letters are addressed to Sir Charles Thomas Newton (1816-1894), who had served in Her Majesty’s consular service for many years[40] and was Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the BM between 1861 and 1885 (ca. 90% of the letters),[41] and to a lesser extent his successor, Alexander Stuart Murray (1841-1904). Given the brevity of this paper, I offer here an overview of his correspondence and discuss summarily the financial side of his dealings with the BM.

Letters from Athens to London and Back

§20 Merlin was not a proto-Aegean archaeologist, as his counterpart, Alfred Biliotti was. He was not even an antiquarian. Using his sharp business acumen, he approached antiquities as an investment from the very beginning. But his interest in collecting appears to have started with natural history specimens and coins, only later involving classical objects. His first dispatch to the BM goes back to the early 1840s – but instead of antiquities, it comprises the collection of birds. According to the List of Specimens of Birds in the Collection of the British Museum (1844), Charles Merlin presented over 20 specimens from Athens that included a short-eared owl, three falcons, two ibises, a number of herons, a little egret, terns, gulls, snipes and a scooping avoset.

§21 The first documented sale of antiquities by Merlin I have been able to find so far dates to November 1859, when he sold by auction, in the London house of S. Leigh Sotheby and John Wilkinson, “a small but very select assemblage of Greek coins in silver and copper; a few Byzantine copper coins; and silver and billon coins of the Crusaders, collected in Greece by the Proprietor, C. L. W. Merlin, Esq., H.B.M. Vice-Consul at Athens”. A similar auction at the same house took place two years later in November 1861, though this time it also included coins in gold, specimens of “extreme rarity and beauty”, a few ancient lead sling bullets and engraved gems all “collected in Greece by the Proprietor, C. L. W. Merlin, Esq., H.B.M. Vice-Consul and Member of the Archaeological Society of Athens”.[42] It is worth noting the emphasis again on the word “Proprietor” and the addition this time of his membership to the Archaeological Society of Athens – a membership that would have added further credence to the objects offered for sale.

§22 At least three more sales of Merlin’s antiquities took place in London: the one in 1864[43] was similar to those of 1859 and 1861. The other two, however, are of interest since Merlin chose not to be mentioned. On 26 June 1866 Puttick and Simpson put for sale a “very interesting collection of Greek antiquities in glass, terracotta, and other material”, some “of the greatest rarity”, collected by “an official residence of many years in Greece and the Levant”. This sale also included a few “highly precious Greek MSS, Gospels and Epistles…of very early date, a superb Byzantine Diptych, inclosing an ancient MS, illuminated missals and other choice manuscripts.”[44] The other sale took place at Sotheby’s in 1871 and comprised “a very choice collection of Greek coins in excellent preservation, a large number of which are believed to be unique, or nearly so; a small quantity of ancient jewellery and some Greek glass; the Property of PERICLES EXEREUNETES.”[45] The 1871 sale alone generated £1,421.[46] The only reason we know today the true identity of the “proprietor”, of the objects sold in 1866 and 1871, is through Merlin’s correspondence with Charles Newton.

§23 Merlin’s effort to conceal the true identity of the “proprietor” of these particular objects stems from developments that took place in Greece between 1865 and 1867, such as the “Aineta aryballos” incident that led to the condemnation of Professor Rhousopoulos to a fine of 1000 drachmas.[47] Rhousopoulos sold this piece to Merlin, who gave it to the BM after Newton had selected it for purchase from the Professor’s collection in Athens. Similar incidents, involving the trafficking of objects by the archaeologist François Lenormant and the Russian Minister Count Alexander Bloudov, started to attract the attention of the authorities in Athens not least because in all three cases the objects that were being trafficked had already been published.[48] On top of that, the British Minister at Athens, Edward Erskine, warned Merlin about the implication of the latter’s name in the “Account of Income and Expenditure of the British Museum” (the institution’s annual report presented to the House of Commons).[49] Erskine remarked that the naming of valuable acquisitions made from Merlin by Newton “appears to me a somewhat imprudent statement to have been made and one which may give you some annoyance at Athens in case it should attract the attention in Greece.”[50] Following that incident, Merlin stated to Newton: “I need hardly add that in future transactions it must be distinctly and clearly understood that my name is not to appear publicly.”[51] After that Merlin’s transactions went largely undercover and, from what I can deduce so far, went unnoticed by the Greek authorities.

“My Dear Mr Newton”: Sourcing Antiquities on Behalf of the British Museum

The great drawback is that I am not wealthy and cannot afford to keep some hundreds of pounds tied up with an interest for a long period. Small profits and quick returns would suit me admirably![52]

§24 Merlin’s correspondence with the department of Greek and Roman antiquities begun early in the 1860s, around the time of Newton’s appointment to the Keepership in 1861. From the correspondence it becomes clear that when Newton visited Athens in 1864 he saw and selected for purchase a number of objects that Merlin then agreed to forward to the BM. From this point onwards a long relationship begun between Merlin and the London institution.[53]

§25 Merlin’s business letters to the BM are a treasure trove regarding the political and social life of Athens at the time, often enriched by Merlin’s fondness to gossip. They include news regarding local excavations and new finds,[54] such as the spectacular discoveries of Heinrich Schliemann and the smuggling of the Trojan antiquities from Athens,[55] the antiquities circulating in the market and the competition among collectors and agents to acquire objects for their own collections or the institutions they represented. There are also several references to the Athenian dealers, their trading methods and the conservation and extra treatment of ancient objects to make them more saleable, as well as the progressive infestation of the market with forgeries that became especially noticeable following the mania that developed over the Tanagra figurines. Merlin also records the traffic of war boats, on board which most of the antiquities and casts for the BM were shipped.

§26 One of the most valuable aspects of the correspondence is the detailed description of the prices attached to antiquities in the Athens market from the 1860s to the 1880s. In this picture, Merlin appears to be a rather small and peripheral player who although buying numerous objects had a limited budget as opposed to the grand collectors in Athens, such as the Ministers of the Sublime Porte, Photiades Bey, and of Russia, Peter Alexandrovich Saburov.[56] And most often in his letters he languishes for a decision to be made by the Trustees with regard to the purchase of some or all of the antiquities he would send to London.[57]

§27 Why was then Merlin collecting antiquities? In his letters to Newton, he makes it abundantly clear that the main motives were profit and “patriotic duty”. The latter is perhaps somewhat surprising given Merlin’s French ancestry: “With regard to price, I am reasonable to abide by what you suggest. 500 pounds although it costs me six times as much as the Venus and the difficulties of getting such articles out of the country have increased tenfold! As a Greek would say, I have offered it first to the BM out of pure Patriotism”[58] (referring here to the bronze “Aphrodite” and Silenus bronzes: Figure 5) – only to add a few years later: “Though I have frequently vowed that every mission of antiquities sent (to) you, should be the last, I have recently seen some groups of terra cotta statuettes which have convinced me to change my mind… I am really too patriotic to allow (them) to part with the hands of foreigners, without first giving you the chance of acquiring them for the British Museum.”[59]

§28 Merlin’s “patriotism”, and perhaps the real reason behind the beginning of his correspondence with the BM, was prompted by the 1864 circular sent to Her Britannic Majesty’s consuls with regard to “the acquisition of antiquities for the British Museum”[60] – a document that was in preparation since 1863 and developed in close collaboration between the Foreign Office and the BM. What was part of the “unofficial duties” of the diplomatic corps abroad since at least the 17th and 18th centuries, now became an official directive that included the “collection of specimens…for transmission to the British Museum”. The duties of consuls and vice-consuls were reconfigured so as to involve the reporting and description of ancient sites, new discoveries and objects available in the market for purchase. Direct exploration of the ruins and ancient objects was also encouraged. Merlin was one of those consuls who complied fully to the circular’s instructions.

§29 There is, however, one more element for Merlin’s passionate interest in collecting that also comes out from his correspondence to Newton. By the 1860s, visiting the house of a dealer, buying antiquities, and discussing recent purchases and discoveries had become in Athens a “gentleman’s activity” – and participation in this activity helped maintain, and in some cases even elevate, one’s social standing.[61] For example, most of the high-ranking, respectable citizens of Athens (foreigners and locals included) had a collection of antiquities and traded in ancient objects – nurtured further by the fact that the first antiquities law of Greece (1834-1899) permitted conditionally the sale of antiquities within the kingdom. With the progressive rise in the price of antiquities, it was becoming clear that the past provided a profitable and fast-growing (because of the speed of authorized and unauthorized archaeological activities) ground for investment – not dissimilar to that of prints and paintings. For example, Merlin often wishes in his letters “small profits and quick returns” for his antiquities dealings – also mentioned in the quotation at the beginning of this sub-chapter – and expresses his frustration to Newton with the inability of the Trustees to either increase the Museum’s annual grant or at least proceed to a faster purchase of Merlin’s antiquities (a process that sometimes took up to three years to complete from the date of the objects’ dispatch from Athens to London).

§30 It appears to me that the 1864 circular and Newton’s visit to Athens that same year re-kindled a business interest that Merlin had in antiquities as early as the 1850s (at least in coins and gems). Combined with the commodification of antiquities as a type of investment and a source of making quick, no matter how small, profits helps to explain further his strong interest in buying and selling Greek antiquities.[62] This is also reinforced by the fact that Merlin was not trading solely with the British Museum (though he probably gave priority to the London institution, and only auctioned objects for sale to other parties once they had been rejected by the BM).[63]

§31 On the other hand, Newton’s interest in Merlin might have been slightly different. Although we have only 25% of the original letters sent by Newton to Merlin, almost 90% of them date to the period between 1869 and 1877, when the former was interested in acquiring casts of the Parthenon from the formatore Napoleone Martinelli. The fact that Newton was more interested in the casts than in Merlin’s objects made the latter feel upset[64] and concerned as to his role.[65] This is also reflected in the frequency of letters, the number of which peaks in 1872 (because of Newton’s interest in the Parthenon casts) – a year that brought very little financial gains for Merlin (other than the sale of 17 coins to the Coins and Medals department: see Tables 1, 2). It is also worth noting that the number of objects purchased per calendar year peaks in 1865 and 1874 (140 and 84 objects respectively, almost half of the total number of objects purchased from Merlin by the BM: Table 2). These numbers are high because they involve objects selected specifically for purchase by Newton himself, while he was in Athens.

By the author.

§32 Thus the antiquities sold to the BM by Merlin appear to represent the consul’s initiative and liberal interpretation of the 1864 circular.[66] His transactions entailed a certain amount of risk, not only because of the legal framework in force in Greece that prohibited altogether the exportation of antiquities without authorization and the dangers of exporting antiquities (issues that the consul was fully aware of and often commented on in his letters), but also because of the financial risk involved. Merlin sourced antiquities from the Athenian dealers (e.g., Rhousopoulos, Lambros, Xakoustis, Palaiologos, and others) who gave him the “right of refusal” – the opportunity to buy these objects from them first. However, for this service, the dealers started to introduce annual interest rates. With the Trustees of the BM frequently taking up to two years (or occasionally more) to purchase antiquities (that were offered to them from numerous individuals and thus had to be placed in a queue) the risk was significant because it left individuals like Merlin exposed and with less capital to re-invest in the antiquities market.[67] For this reason, Merlin often purchased antiquities without asking Newton if he was interested in them and then tried to force their sale by dispatching them to the BM and describing their “rarity” and “beauty” – a financially risky endeavor, that often, but not always, proved Merlin right.[68]

§33 The way Merlin was trying to make money resembles that of a casino player (the addiction included) – where one is also running a risk of losing everything. He started with a small sum and by buying objects from the local market tried to increase his capital by re-selling them to the BM as well as to private collectors (e.g., Felix Slade and the pre-Raphaelite painter Sir Frederic Leighton), or other institutions (e.g., what is today the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh) and, as mentioned above, in auction sales.

§34 As for his sourcing methods, his writings recall a farmer’s expectation of his field to yield produce: “owing to the little rain we have had this year and the dryness of the ground only few antiquities have been discovered this winter and I have seen nothing good.”[69] Depending on market demands, if the antiquities bought were not deemed profitable, he would exchange them for new ones with one of the Athenian dealers.[70] Like a good trading consul and antiquities agent, Merlin was “transporting” these “goods” from London to Athens in collaboration with the Admiralty and Customs in Britain. He would also occasionally act as a middleman between the BM and the Athenian art dealers (as in the case of the “Aineta aryballos”, which was originally bought from Professor Rhousopoulos). In this respect, his transactions involved, to use the appropriate shipping term, “a pier-to-house” delivery system – the development of an antiquities consular agency that became standard practice for the second half of the 19th century for most of Her Majesty’s consular service stationed around the Mediterranean.

§35 So, how successful was Merlin in generating income out of his antiquities dealings with the BM? Although we will never know the amount originally spent by Merlin in sourcing the antiquities he eventually sold to the Museum, from the correspondence I have been able to study, about 26 lots (objects sold as groups – the BM’s preferred method with regard to the purchase of bulk antiquities);[71] the number of objects purchased per calendar year varying from one to 140, with an average of 18 objects per year[72]: Table 2). These sales generated at least £4,373 3s[73] – a good amount but certainly not exorbitant, when we consider that the Patras bronze Marsyas (H: 76cm; BM 1876,1125.1) was purchased from the Parisian auction house of Rollin and Feuardent in 1876 for £2,200, while the marble Spinario (H: 76.2cm; BM 1880,0807.1; a Roman copy of a Greek original) was purchased in 1880 from Alessandro Castellani for £4,000[74] (for Merlin’s most expensive sales to the Museum, a bronze “Aphrodite” and a bronze Silenus-shaped lamp-stand, each sold for £500, see Figure 5).

§36 In this respect, the Greek and Roman antiquities department of the BM, which at the time spent around £500 to £1,500 for ordinary purchases,[75] would on average dedicate around £160 annually for purchases from Merlin – and this amount, in my view, reflects well the position of Merlin within the broader system of antiquities purchases by the BM’s Greek and Roman antiquities department at the time. This average amount, which in reality varied annually, would have secured a small, but regular, addition to Merlin’s income. We have to bear in mind, however, that this amount would at times be substantially higher, since the BM represents only one side of Merlin’s business in antiquities – with private collectors and auction houses (for which very few records today exist) representing the other, occasionally more profitable, side for “disposing” his “property”.

Concluding Remarks

It seems to me that auctioneers and antiquarians who are accustomed to talk about centuries, as if they were hours, forget time altogether![76]

§37 Charles Merlin was only one of many from whom the BM purchased annually Greek and Roman antiquities. Yet he appears to have been among the most prolific, if not the most important, direct providers of antiquities sent to the BM from the kingdom of Greece during the 1860s-1880s.[77] Undoubtedly this is only the story of Merlin and not of every foreign agent operating in Greece during the time of the first antiquities law (1834-1899), whose motives differed considerably. But unlike the academic art dealers (Rhousopoulos and Lambros senior) and foreign scholarly antiquities agents (Rayet and Hirschfeld), or even the local private diggers/secondary dealers (Xakoustis and Palaiologos), Merlin is part of the British diplomatic corps that from 1864 onwards developed “a pier-to-house” delivery system to supply the BM with antiquities from across the Mediterranean, now on a more official and organized basis than ever.

§38 Although the circular of 1864 certainly contributed further to the consolidation of a direct line of communication between the consular service in Greece and the BM, Merlin’s special interest in the subject was also supported by the realization that for a consul based in the Piraeus and paid an ordinary salary (i.e., within the diplomatic corps), antiquities provided an opportunity for making small profits. Making gains from the difference in the original purchase price and the final sale price was a practice that Merlin had learned as a trading agent between the 1830s and 1860s, at a time when it was common practice for unpaid personnel to make a living through their license to trade.[78]

§39 The financial motive, however, despite being a common denominator for most, if not all, of the individuals involved in the sourcing and trafficking of antiquities, also blurs the nuances and different motives involved by different parties in the story of the 19th-century antiquities trafficking; when, for example, a number of those involved developed real interests in the advancement of knowledge and the more systematic exploration of the past making the distinction between “looter” and “archaeologist” in the second half of the 19th century as much semantic as anything else.

§40 Apart from the profit that the trafficking of antiquities could generate and the 1864 circular, one cannot fail but to detect in Merlin’s correspondence with the BM his anxiety to be part of the higher echelons of Athenian society. The purchase and trafficking of antiquities along with his long lasting association with the BM (seen in this case from the eyes of an expat) appears to me to have allowed him to participate in this highly expensive “gentleman’s activity” with the intensity and passion that he did. Merlin belongs to those who early on in the 19th century saw the past as a means of making “small profits and quick returns” and of maintaining a high social standing within the local community, while at the same time fulfilling his duty to Her Majesty’s Service. It is from this perspective that his dealings with the BM should be assessed.

Figures

Source: © Trustees of the British Museum.

Source: © Trustees of the British Museum and http://www.flickr.com/photos/28772513@N07/6294960292/

sizes/o/in/photostream/

Source: © Trustees of the British Museum.

Source: © Trustees of the British Museum.

Source: © Trustees of the British Museum.

Source: © Trustees of the British Museum.

Source: © Trustees of the British Museum.

Bibliography

Barchard, D. 2006. “The Fearless and Self-Reliant Servant: The Life and Career of Sir Alfred Biliotti (1833-1895).” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici 48:5-53.

Challis, D. 2008. From the Harpy Tomb to the Wonders of Ephesus. British Archaeologists in the Ottoman Empire, 1840-1880. London.

Clairmont, C. W. 2007. Fauvel. The First Archaeologist in Athens and his Philhellenic Correspondents, Zurich.

Cottrell, P. L. 2007. The Ionian Bank. An Imperial Institution, 1839-1864, volume 1. Athens.

Dickie, J. 2008. The British Consul. Heir to a Great Tradition. London.

Donkow, I. 2004. “The Ephesus Excavations 1863-1874 in the Light of the Ottoman Legislation on Antiquities.” Anatolian Studies 54:109-117.

Dyson, L. D. 2006. In Pursuit of Ancient Pasts. A History of Classical Archaeology in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. New Haven.

Farnaud, H. 2009. L’Ambassade de France en Grèce: une visite sans protocole. Athens.

Fitton, J. L. 1989. “Esse Quam Videri: A Reconsideration of the Kythnos Hoard of Early Cycladic Tools.” American Journal of Archaeology 93:31-39.

———. 1991. Heinrich Schliemann and the British Museum (British Museum Occasional Paper 83). London.

Green, P. J. 1827. Sketches of the War in Greece. London.

Hussey, J. M. 1995. The Journals and Letters of George Finlay. Vol. 2. Finlay-Leake and other correspondence. Camberley.

Jenkins, I. 1992. Archaeologists and Aesthetes in the Sculpture Galleries of the British Museum 1800-1939. London.

Jones, R. 1971. The Nineteenth-century Foreign Office. An Administrative History. London.

Kalogeropoulou, A. G. 1974. “Η περί τα αρχαία δραστηριότης του υποπροξένου της Βρεταννίας στη Μύκονο (1821-1841).” In Μελέται προς τιμήν Στρατή Γ. Ανδρεάδη επί τη συμπληρώσει τριακονταετούς πανεπιστημιακής διδασκαλίας, vol. 3, 539-570. Athens.

Kalpaxis, T. E. 1990. Αρχαιολογία και Πολιτική. Ι. Σαμιακά Αρχαιολογικά 1850–1914. Rethymno.

Marchand, S. L. 1996. Down from Olympus: Archaeology and Philhellenism in Germany, 1750-1970. Princeton.

Marchand, S. L. 2009. German Orientalism in the Age of Empire: Religion, Race, and Scholarship. Cambridge.

Merlin, C. W. L. 1872. “Piraeus, Report.” In Accounts and Papers: Consular Establishments, vol. 60, session 6 February–10 August 1872, House of Commons, London, 207-213.

Patrizio Gunning, L. 2009. The British Consular Service in the Aegean and the Collection of Antiquities for the British Museum. Surrey.

Platt, D.C.M. 1971. The Cinderella Service: British Consuls since 1825. London.

Stoneman, R. 2010. Land of Lost Gods: the Search for Classical Greece, rev. edition. London.

Trümpler, C. 2008. Das grosse Spiel: Archäologie und Politik zur Zeir des Kolonialismus (1860-1940). Köln.

Zimi, E., and A. Sideris. 2003. “Χάλκινα Σκεύη από το Γαλαξείδι: Πρώτη Προσέγγιση.” In Το Γαλαξείδι από την αρχαιότητα έως σήμερα, ed. P. Themelis and R. Stathaki-Koumari, 35-60. Athens.

Abbreviations

BM Account 1866: An account of the income and expenditure of the British Museum, for the financial year ended 31st March 1866; of the estimated charges and expenses for the year ending 31st March 1867, and sum necessary to discharge the same; number of persons admitted, and progress of arrangement; &c.

BM Account 1867: An account of the income and expenditure of the British Museum, for the financial year ended 31st March 1867; of the estimated charges and expenses for the year ending 31st March 1868, and sum necessary to discharge the same; number of persons admitted, and progress of arrangement; &c.

[1] For more recent episodes in the trafficking of antiquities using the “diplomatic pouch” see: http://www.thebrokeronline.eu/en/Articles/Safe-havens/Diplomats-and-art-smuggling#f8.

[2] Patrizio Gunning 2009. It focuses on 1815-1864, i.e., the years of the British protectorate of the Ionian Islands.

[3] E.g., Kalogeropoulou 1974; Jenkins 1992, esp. pp. 168-195; Barchard 2006; Clairmont 2007. Generally on politics and archaeology in 19th-century Mediterranean see: Kalpaxis 1990; Marchand 1996; 2009; Donkow 2004; Dyson 2006; Challis 2008; Trümpler 2008; Stoneman 2010.

[4] http://research-bulletin.chs.harvard.edu/2012/10/17/guns-drugs-and-the-trafficking-of-antiquities-archaeology-in-19th-century-greece/.

[6] http://research-bulletin.chs.harvard.edu/2012/11/15/of-grave-hunters-earth-contractors-a-look-at-the-private-archaeology-of-greece/.

[8] He was baptized on July 4, 1821 in the church of St Botolph without Bishopsgate. In the church registers, his father gave Boulogne-sur-Mer, opposite Dover, as the city of residence and his profession as “gentleman”.

[9] I have not been able to trace further François-Nicolas Merlin in the British National Archives or his exact relationship to the de Douai.

[10] “Κάρολος Μέρλεν” in the satirical Greek newspaper “To Asty”, vol. 2, issue 78, 15 March 1887, p. 4: “εν Dill της Αγγλίας ένθα και εγεννήθη ο κ. Μέρλεν τυχών επιμελημένης ανατροφής.” By “Dill”, is the author of this article referring here to “Dulwich” in south London?

[11] Jones 1971, p. 42. Among his duties was to look after the accounts of the consulate and transcribe dispatches. See also, Platt 1971 and Dickie 2008.

[12] Cottrell 2007. The second volume, which is currently forthcoming, will include more details on Merlin’s involvement in the Bank. I would like to thank Mrs Andromache Theodoropoulou, of the Historical Archive of Alpha Bank (Greece), for the information she was able to give me on the Ionian Bank.

[13] The “trading consul” would develop into what is today, sometimes, known as the “commercial attaché”.

[14] For this crossover of commercial and political interests and the debates it sparked in Britain see Patrizio Gunning 2009, pp. 36-41.

[15] For example, Lysimachos Kalokairinos, vice-consul at Herakleion (Candia) in Crete who had a rather bad reputation as a rapacious moneylender. He and his family met a tragic end when they were burnt alive in the 6 September 1898 uprising (Barchard 2006, 17, 27-28, 39 and n. 104).

[16] E.g., The Times, 22 May 1858, p. 10: “Before everything else the trading Consuls and Vice-Consuls must be done away with. They bring the greatest disrepute to the Consular body.” The author of The Times expresses strong views against the appointment of foreigners as vice-consuls and consular agents, not least because he saw in their appointment a conflict of interests (for a discussion see also, Patrizio Gunning 2009, 37-39).

[17] Their marriage certificate from St Marylebone Christ Church does not mention Charles’ parents. Isabella’s father is today mostly known for a book he wrote about Greece in the years of the war of independence (Green 1827).

[18] Hussey 1995, pp. 642 and 684, where he is described as “nephew” of John Green, perhaps the brother of his wife’s father. This John Green may be the diplomat who served as vice-consul at Nauplion between 1835-1838 and was consul (and thus Charles’ line manager) in the Piraeus from 1838 to 1852/1853, when he was transferred to Alexandria (Foreign Office List for 1857, p. 55).

[19] These were Camilla Augusta Dorothea (6/10/1848-22/10/1850), Samuel B. Walter (6/9-9/9/1852) and Bickerton Pemell Lyons (17/10/1853-10/7/1855). The mortality rate for infants and young children at the time was about 150-200 out of 1000.

[20] Charles Merlin junior started the negotiations with the French delegation in Athens regarding the construction of a mansion to house the French embassy. The building, constructed between 1893 and 1895 by the Psycha brothers and the architect Anastasios Metaxas, is today known as “Hôtel Merlin de Douai” and has since 1896 housed the French Embassy in Athens. Between 1893 and 1913 it was leased to the French delegation, having passed as part of Arietta Isabella’s dowry (one of Merlin’s daughters) to her husband, the politician and poet, Constantinos Manos. The latter continued the negotiations for the sale of the mansion (completed in April 1913, the same month Manos was killed in action during the Balkan wars). For the history of the house see Farnaud 2009.

[21] Sidney Merlin is today mostly remembered as a botanist and gold and bronze medalist for team GB in the men’s single and double trap shooting in the 1906 intercalated games in Athens. He also participated in the 1896 Athens and 1900 Paris games. His first wife was Zaira Theotoki, daughter of the Corfiot Prime Minister Georgios Theotokis. After their divorce, Sidney married Katia Inglessi. He had extensive property in Corfu, central Greece, Attica, and Crete. In the 1920s he introduced the “Washington Navel” orange variety to Corfu, and from that day onwards this variety is locally known as “Merlin oranges”. He also introduced the kumquat tree to Corfu, which provides today a Corfiot specialty sweet.

[22] Augustus Merlin followed in his father steps. He became vice-consul at Volos in the 1880s and Consul in 1917 (until 1920). Today he is mostly remembered for his interest in microscopes and astronomy. A member of the Royal Microscopical Society, Augustus became in 1893 a member of the British Astronomical Association. While at Volos, he used on the roof of the British consulate an 8 ½ reflector telescope and a transit instrument, the latter serving for many years to regulate Volos’ town clock. He settled in West Ealing following his retirement where he set up an observatory. In his honor the Merlin Medal and Gift was set up funded by part of Mrs Merlin’s bequest (presented by the British Astronomical Association since 1960).

[23] For intermittent periods he had already served as acting Consul at the Piraeus (in 1859 and 1864).

[24] Charles Newton earned in 1868, as Keeper of the Greek and Roman Antiquities department, £600 p.a.

[25] All the “Commercial reports received at the Foreign Office from Her Majesty’s consul” are available online in the House of Commons Parliamentary Papers website: http://parlipapers.chadwyck.co.uk.

[28] Cf. Sir Alfred Biliotti’s 54 years of service (Barchard 2006). Most of the information on Merlin’s Foreign Office service comes from The foreign officer list for 1877, p. 149. Some information about his long stay in Greece comes from the article: “Κάρολος Μέρλεν” in the satirical Greek newspaper “To Asty”, vol. 2, issue 78, 15 March 1887, p. 4.

[29] Ionian Bank Court of Directors minute books, vol. 5 (part 2), no. 895 (November 6, 1891): http://library-2.lse.ac.uk/archives/pdf/ionian-bank/Vol5-part%202.pdf

[30] Ionian Bank Court of Directors minute books, vol. 7 (part 2), no. 316 (September 11, 1896): http://library-2.lse.ac.uk/archives/pdf/ionian-bank/Vol7-part%202.pdf

[31] A good but relatively modest amount when compared, for example, to that of his contemporary, and considerably richer, compatriot Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks (1826-1897), who had £120,316 1s 4d (according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry).

[32] For a full assessment of Merlin’s diplomatic career one has to consult the National Archives at Kew: FO 582 (seven letter books for the period 1841-1879) and the annual political, consular and commercial reports: FO 32/297 (1861), FO 32/306 (1862), FO 32/339 (1864), FO 32/389 (1868), FO 32/397 (1869), FO 32/411 (1870), FO 32/420 (1871), FO 32/430 (1872), FO 32/440 (1873), FO 32/451 (1874), FO 32/460 (1875), FO 32/472 (1876), FO 32/484 (1877), FO 32/504 (1878), FO 32/515 (1879), FO 32/525 (1880), FO 32/534 (1881), FO 32/546 (1882), FO 32/553 (1883), FO 32/559 (1884), FO 32/569 (1885), FO 32/580 (1886), FO 32/594 (1887); and the foreign office circulars for the period 1831-1894 (Consulate of Piraeus), now in the archive of the residence of the British Ambassador at Athens.

[34] Merlin 1872, 210. Among his unofficial duties, we learn, the following: “English travellers likewise freely avail of the Consul’s advice and assistance, and have apparently, a high opinion of Consular abilities, as he is expected to settled disputed accounts with hotel-keepers, &c., and to bit to a nicety the exact price which should be charged by muleteers, hackney-coach drivers, and others…The usual office hours are from 9 till 12 in the morning, and from 2 till 4 o’clock in the afternoon. But frequently much earlier and later, when there is any duty of importance to be performed.”

[37] It includes 34 coins also purchased from Merlin. Seven more objects were donated, while 13 were purchased through his intervention. Eight more objects came to the museum from other sources but were formerly in Merlin’s possession. All these numbers should be considered provisional since they derive only from the BM’s “Merlin” search engine (named after the Arthurian wizard and not the consul!). They have not yet been crosschecked with the number of objects mentioned in the letters and the BM’s registers. Although this collection is sizeable, it cannot, be compared to the almost 5000 objects that the Museum sourced from Alfred Biliotti, who, like Charles Newton, George Dennis and other “antiquarian-consuls”, was collecting objects by conducting excavations “on behalf of the Trustees”. Merlin relied exclusively on the excavations of the Athenian “private diggers” and the market for sourcing and trafficking antiquities.

[38] A search using the BM’s search engine generates 14 forgeries from Charles Merlin: 12 figurines and two lamps. They were purchased in 1865, 1876-1877, 1879-1882, and even in 1892 (the last object sold to the BM by Merlin was a fake figurine: BM1892,0824.1).

[39] I also include here a few letters sent by Merlin to Franks, which are today kept in the archives of the BM’s European Prehistory department. The Merlin letters at the BM are being studied by the author in collaboration with the department of Greek and Roman antiquities and will be published in a monograph that is currently in preparation.

[41] The correspondence that now exists in the BM between Merlin and Newton ends rather abruptly, though it is possible that they continued to correspond privately. In the last few years of their correspondence they had often disagreed on the genuineness of figurines said to be from Myrina on Lemnos and Smyrna in Asia Minor, which Newton considered largely fakes and Merlin was desperately trying to sell at a very high price since he had made a purchase placing substantial capital on them – but which, unfortunately for him, did not generate the income he was expecting to accrue from their sale.

[42] The Athenaeum, no. 1670, Oct. 29 (1859), p. 551; The Athenaeum, no. 1774, Oct. 26 (1861), p. 528.

[44] The Athenaeum, no. 2016, Jun. 16 (1866), p. 787. That Merlin was dealing in manuscripts and Byzantine antiquities is also known from his correspondence to Newton. This auction was repeated in July 13, with the new advertisement being more detailed with regard to the Manuscripts on sale: The Athenaeum, no. 2019, Jul. 7 (1866), p. 2. Among numerous other objects of art and curiosity (such as an ivory bust of Voltaire), the sale included gospels and epistles of St. Chrysostom of the 12th and 14th centuries; an 11th century MS of John Chrysostom; and a Lectionarium of the 11th century enclosed in a “superb Byzantine case of carved ivory and silver gilt of the eighth century – probably the finest example of its kind extant.”

[45] The Athenaeum, no. 2263, Mar. 11 (1871), p. 291; Charles Merlin to Charles Newton, Athens, February 6, 1871: “You have no doubt seen the catalogue of my coin sale, under the euphorius disguise of “PERICLES EXEREUNETES” which is to come off, Bismarck permitting, on the 16th proximo and two following days.”

[47] “These are thanks he gets for having published it!”: Charles Merlin to Charles Newton, Athens, February 11, 1867.

[48] Charles Merlin to Charles Newton, Athens, October 5, 1866: “By-the-by, Mr LeNorman and Mr Bloudoff have nearly rendered the exportation of antiquities impossible from this – the former by publishing an account of what he carried off in the French Papers and the latter by his blunder about the marble bas-reliefs.”

[50] Original letter sent to Merlin on June 23, and copied in the letter to Charles Newton from Cephalonia of July 28, 1867.

[51] Charles Merlin to Charles Newton, Cephalonia, July 28, 1867. It is worth noting that Merlin’s name had already been mentioned in the BM’s report to the House of Commons in 1866 in relation to the sale of the “Aineta aryballos”: “a small Greek vase, of the kind called Aryballos, found near Corinth; purchased of Mr. Charles Merlin, British Vice-Consul at Athens. This vase has a number of names inscribed on it in archaic characters, and is one of the earliest known specimens in which Greek writing occurs. Engraved in the Annali of the Roman Institute di Corrispondenza Archaeologica, xxxiv, tav. d’agg. a.” (BM Account 1866, p. 19); and Merlin’s name was mentioned again in the Museum’s Accounts to the House of Commons for 1872 and 1884-1885.

[53] The letter books in the department of Greek and Roman antiquities begin in 1864. Some earlier letters, perhaps for the period 1861 and 1863, may still be kept in the letter books of the Middle East department. More material may also exist in the BM’s Central Archives and the department of Coins and Medals.

[54] E.g., on the involvement of Merlin in the sale of the so-called “Kythnos bronzes” see Fitton 1989; on the Galaxidi “bronzes” see Zimi and Sideris 2003.

[56] E.g., Charles Merlin to Charles Newton, Athens, July 15, 1869: “Photiades pays enormous prices for anything at all good, that makes it difficult to buy any more antiquities at present.”

[57] It is a clear tactic of Merlin to send objects to Newton, sometimes even for conservation, and then asking him to buy them. Merlin was quite forceful and stubborn when it came to the “disposal” of “my antiquities” as he often calls them.

[60] 15 December 1864; quoted in full by Patrizio Gunning 2009, 187-188 but not discussed in any detail; for the text and a brief commentary see: http://research-bulletin.chs.harvard.edu/2012/11/29/to-serve-and-to-source-a-trading-consul-at-the-service-of-the-british-museum/.

[61] Charles Merlin to Charles Newton, The Piraeus, Athens, February 6, 1875: “…I have purchased the rhyton [the donkey-shaped kantharos, BM 1876,0328.5] from Xacoustis…I have had to pay more than the £60 you say you will give for it as Photiades Bey has just returned here and all our dealers have raised their prices in consequence…Rayet offered him 1500 francs for the rhyton which he refused. The body of the vase is broken but all the pieces are perfect and the head of the ass, or mule as Savouroff calls it, is quite perfect. The colour is certainly that of a mule. I know I shall lose by it but I don’t intend it to adorn any other Museum but ours if I can prevent it.” See Figure 8.

[62] To these motives one could also add Merlin’s pseudo-ideal on classical Greek beauty: “I don’t have any respect for any antiquity (except an old man or woman) when it ceases to be beautiful” (Charles Merlin to Charles Newton, The Piraeus, November 2, 1871). And in a similar vein: “I was obliged to secure Mr Rhousopoulos’ gems, as Curtius has made him an offer for them. They consist of all the Helleno-Phoenecian gems, or whatever you call them, an ugly lot – which I never have thought of investing money in for my own account, but which I know you would” (Charles Merlin to Charles Newton, Athens, January 29, 1872).

[63] This is corroborated further by the fact that after his retirement in 1887 and until 1892, Merlin was trying to sell to the BM those objects that remained unsold in his possession but which he had probably purchased prior to his departure from Greece.

[64] Charles Merlin to Charles Newton, Athens, April 22, 1871: “My disquiet on opening your large official envelope and discovering that, instead of a cheque for £210 it contained drawings of the Frieze of the Parthenon may be more sadly conceived than described! Such heartless jokes are enough to freezeone’s blood, and I can only say I hope you are not in jest for I don’t like jokes of that kind!”.

[65] Charles Merlin to Charles Newton, Athens, February 14, 1872: “My dear Newton, do (try to) be a little reasonable. It is quite uncertain “whether we live to see the first of April seventy three (excuse the rhyme) for I have neither discovered the Elixir of Life nor the Philosopher’s Stone. It is clear time that if you can’t find funds to purchase such articles…it is useless my thinking of investing money again in antiquities with the remote hope of you buying them…from my great grand children. If I was Rothschild I could afford to wait…“Don’t ride a willing horse to death”…”.

[66] Newton, who occasionally visited Athens (though not as frequently as Merlin wished), would select objects that the consul was then asked to forward him to London. Consequently, Newton’s selection influenced the number of objects traded by Merlin (see e.g., the number of objects sold in 1865 and 1874 that included Newton’s selection: Table 2).

[67] Charles Merlin to Charles Newton, The Piraeus, April 20, 1885: “It will be to the advantage of the Museum, as well as my own, as the money would be reinvested in new objects.”

[68] The money paid by the BM to Merlin did not come from the BM’s own funds, but from a state-subsidized annual grant allocated to new acquisitions.

[70] Athens, December 28, 1872: “I shall probably exchange them with Rhousopoulos for something more to my taste.”

[71] The BM, as many other major European museums at the time, preferred group purchases because it allowed them to program their budget for the coming year. Being a national institution, they had to have their budget approved by the government through the House of Commons and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Newton often complains to Merlin about the shortage in funding: “the government has not yet even passed our Estimates; and we have not at this moment money to pay the salaries for next month” (London, May 26, 1868).

[72] The average is lower (10 objects per year), if one removes the 1865 and 1874 sales that represent largely Newton’s selection of objects while in Athens.

[73] This amount should be considered approximate as the prices mentioned in the letters should be compared against those mentioned in the registers of the BM’s Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities (and this is very much a work in progress). It is worth noting that the total expenses in new acquisitions for the Greek and Roman department for 1865-1866 (when the “Aphrodite” was acquired for £500) was £1,383 (i.e., 36% of the available amount: BM Account 1866, p. 2).

[74] The annual salary of the Head of the British diplomatic service was £5,000. On diplomatic salaries and their substantial discrepancies see also, Patrizio Gunning 2009, 41-43.

[75] When an extraordinary (i.e., unscheduled) purchase had to be made the government would either raise the adequate funds or complement the BM’s ordinary budget with the remaining amount.

[77] The vast majority of Greek and Roman antiquities at that time arrived at the BM either through excavations sponsored by the Trustees in areas outside the kingdom of Greece or indirectly through Alessandro Castellani of Rome and M.H. Hoffman and Rollin & Feuardent of Paris among numerous other sources.